Virus grows tube to insert DNA during infection then sheds it

December 16, 2013

|

|

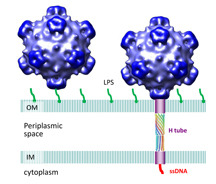

Researchers have discovered a tube-shaped structure that forms temporarily in a certain type of virus to deliver its DNA during the infection process and then dissolves after its job is completed. The virus is pictured here infecting an E. coli cell. The tube attaches to the cell's inner and outer membranes, bridging the "periplasmic space" in between. (Purdue University image/Lei Sun) |

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — Researchers have discovered a tube-shaped structure that forms temporarily in a certain type of virus to deliver its DNA during the infection process and then dissolves after its job is completed.

The researchers discovered the mechanism in the phiX174 virus, which attacks E. coli bacteria. The virus, called a bacteriophage because it infects bacteria, is in a class of viruses that do not contain an obvious tail section for the transfer of its DNA into host cells.

"But, lo and behold, it appears to make its own tail," said Michael Rossmann, Purdue University's Hanley Distinguished Professor of Biological Sciences. "It doesn't carry its tail around with it, but when it is about to infect the host it makes a tail."

Researchers were surprised to discover the short-lived tail.

"This structure was completely unexpected," said Bentley A. Fane, a professor in the BIO5 Institute at the University of Arizona. "No one had seen it before because it quickly emerges and then disappears afterward, so it's very ephemeral."

Although this behavior had not been seen before, another phage called T7 has a short tail that becomes longer when it is time to infect the host, said Purdue postdoctoral research associate Lei Sun, lead author of a research paper to appear online in the journal Nature on Dec. 15.

The paper's other authors are University of Arizona research technician Lindsey N. Young; Purdue postdoctoral research associate Xinzheng Zhang and former Purdue research associate Sergei P. Boudko; Purdue assistant research scientist Andrei Fokine; Purdue graduate student Erica Zbornik; Aaron P. Roznowski, a University of Arizona graduate student; Ian Molineux, a professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at the University of Texas at Austin; Rossmann; and Fane.

Researchers at the BIO5 institute mutated the virus so that it could not form the tube. The mutated viruses were unable to infect host cells, Fane said.

The virus's outer shell, or capsid, is made of four proteins, labeled H, J, F and G. The structures of all but the H protein had been determined previously. The new findings show that the H protein assembles into a tube-shaped structure. The E. coli cells have a double membrane, and the researchers discovered that the two ends of the virus's H-protein tube attach to the host cell's inner and outer membranes.

Images created with a technique called cryoelectron tomography show this attachment. The H-protein tube was shown to consist of 10 "alpha-helical" molecules coiled around each other. Findings also showed that the inside of the tube contains a lining of amino acids that could be ideal for the transfer of DNA into the host.

"This may be a general property found in viral-DNA conduits and could be critical for efficient genome translocation into the host," Rossmann said.

Like many other viruses, the shape of the phiX174 capsid has icosahedral symmetry, a roughly spherical shape containing 20 triangular faces.

The research has been funded by the National Science Foundation, U.S. Department of Energy, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Writer: Emil Venere, (765) 494-4709, venere@purdue.edu

Sources: Michael Rossmann, 765-494-4911, mr@purdue.edu

Lei Sun, 765-494-4908, sun167@purdue.edu

Bentley A. Fane, 520-626-6634, bfane@email.arizona.edu

Note to Journalists: An electronic or hard copy of the research paper is available by contacting Nature at press@nature.com or calling (212) 726-9231.

ABSTRACT

Icosahedral bacteriophage ΦX174 forms a tail for DNA transport during infection

Lei Sun1,*, Lindsey N. Young2,*, Xinzheng Zhang1,* Sergei P. Boudko1,†, Andrei Fokine1, Erica Zbornik1, Aaron P. Roznowski2, Ian Molineux3, Michael G. Rossmann1, and Bentley A. Fane2

1Department of Biological Sciences, Purdue University

2School of Plant Sciences and the BIO5 Institute, University of Arizona

3Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, Institute for Cell and Molecular Biology, The University of Texas at Austin

*These authors have contributed equally

†Current address: The Research Department, Shriner's Hospital for Children, Portland, OR

Prokaryotic viruses have evolved various mechanisms to transport their genomes across bacterial cell walls: barriers that can contain two lipid bilayers and a peptidoglycan layer1. Many bacteriophages utilize a tail to perform this function, whereas tail-less phages rely on host organelles, such as plasmid-encoded receptor complexes and pili2-5. However, the tail-less, icosahedral, single-stranded (ss) DNA ΦX174-like coliphages do not fall into these well-defined infection paradigms. For these phages DNA delivery requires a DNA pilot protein6. Here we show that the ΦX174 pilot protein H oligomerizes to form a tube whose function is most probably to deliver the DNA genome across the host's periplasmic space to the cytoplasm. The 2.4 Å resolution crystal structure of the in vitro assembled H protein's central domain consists of a 170 Å-long α-helical barrel. The tube is constructed of 10 α-helices with their N-termini arrayed in a right-handed super-helical coiled-coil and their C-termini arrayed in a left-handed super-helical coiled-coil. Genetic and biochemical studies demonstrated that the tube is essential for infectivity but does not affect in vivo virus assembly. Cryo-electron tomograms have shown that tubes span the periplasmic space and are present while the genome is being delivered into the host cell's cytoplasm. Both ends of the H protein contain trans-membrane domains, which anchor the assembled tubes into the inner and outer cell membranes. The central channel of the H protein tube is lined with amide and guanidinium side chains. This may be a general property of viral DNA conduits and is likely to be critical for efficient genome translocation into the host.