December 7, 2016

Greenland wasn't always covered in ice, scientists say

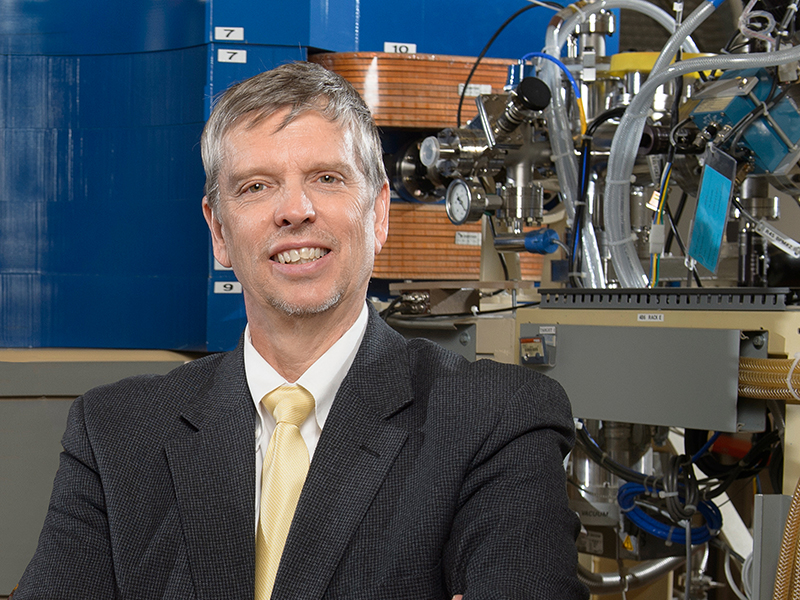

Rare isotopes left in bedrock below Greenland's ice sheet more than a million years ago are evidence that the ice sheet once disappeared, and could disappear again, which would wreak havoc on coastal regions worldwide, says a research team, which included Marc Caffee, professor of physics and astronomy at Purdue University. Caffee used a gas-filled magnet in Purdue's PRIME Lab Accelerator to find the isotopes. (Purdue University photo by John Underwood)

Download image

Rare isotopes left in bedrock below Greenland's ice sheet more than a million years ago are evidence that the ice sheet once disappeared, and could disappear again, which would wreak havoc on coastal regions worldwide, says a research team, which included Marc Caffee, professor of physics and astronomy at Purdue University. Caffee used a gas-filled magnet in Purdue's PRIME Lab Accelerator to find the isotopes. (Purdue University photo by John Underwood)

Download image

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. – For a long while, more than a million years ago, Greenland wasn't covered in ice, scientists announced this week.

That may not seem like the biggest news in science, except for this: The Greenland ice sheet is the second largest ice cube on the planet, after the Antarctic ice sheet. If the Greenland ice sheet were to melt – if it is even possible for the ice sheet to melt – then it's also possible that the planet's oceans might rapidly rise five or six meters, or more than twenty feet, and wreak havoc on coastal cities worldwide.

Before now, scientists didn't know whether Greenland's ice sheet was so stable that it would just weather any climate changes, or if there were ever a period in which Greenland was, if not verdant, at least a bit rocky.

It turns out there was, in fact, a time when it was largely ice-free, perhaps for as long as 250,000 years, more than a million years ago.

Scientists were able to determine this because the bare rock during that time was exposed to cosmic rays in the atmosphere, says Marc Caffee, professor of physics and astronomy at Purdue University.

"We now have pretty conclusive evidence that for a time that ice wasn't there," Caffee says. "That's big. That's new. It's probably not much different in temperature now than it was then, so we shouldn't count on that ice sheet never melting again."

Caffee's lab, the Purdue Rare Isotope Measurement (PRIME) Laboratory, was able to determine that the bedrock of Greenland had been exposed to the atmosphere and cosmic rays from outer space by looking at rock samples that had been recovered by a U.S. scientific team from beneath nearly two miles of ice in 1993.

It was only in the past year that Purdue's PRIME lab developed techniques using a gas-filled magnet attached to a particle accelerator that was sensitive enough to detect the beryllium-10 and aluminum-26 atomic isotopes. These isotopes had been created by the cosmic rays striking the rock and had been hiding beneath the ice for more than a million years.

The results of all of this scientific sleuthing were published in this week's Nature.

The lead author on the Nature paper, Joerg Schaefer, a paleoclimatologist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, says it's possible that the Greenland ice sheet could go away again.

"Unfortunately, this makes the Greenland ice sheet look highly unstable," he said in a Columbia University news release. "With human-induced warming now well underway, loss of the Greenland ice has roughly doubled since the 1990s; during the last four years by some estimates, it shed more than a trillion tons [of ice]."

Additional authors on the paper include Richard Alley, Pennsylvania State University; Nicolas Young and Roseanne Schwartz, Columbia University; Greg Balco, the University of California-Berkeley; Jason Briner, University of Buffalo; and Anthony Gow, U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory.

Writer: Steve Tally, 765-494-9809, steve@purdue.edu, @sciencewriter

Sources: Marc Caffee, 765-494-2586, mcaffee@purdue.edu

Joerg Schaefer, 845-365-8703, schaefer@ldeo.columbia.edu

Extended periods during the Pleistocene in which Greenland was nearly ice-free

Joerg M. Schaefer, Robert C. Finkel, Greg Balco, Richard B. Alley, Marc Caffee,

Jason P. Briner, Nicolas E. Young, Anthony J. Gow and Roseanne Schwartz

The Greenland Ice Sheet (GIS) contains the equivalent of 7.4 metres of global sealevel rise1. Its stability in our warming climate is therefore a pressing concern. However, the sparse proxy evidence of the palaeo-stability of the GIS means that predictions of its history are controversial (compare refs 2 and 3 to ref. 4). Here we present evidence that Greenland was deglaciated for extended periods during the Pleistocene epoch (from 2.6 million years ago to 11,700 years ago), based on measurements of cosmic-ray- produced beryllium and aluminum isotopes (10Be and 26Al) in a bedrock core from beneath the GIS summit. Models indicate that when this core site is ice-free, any remaining ice is concentrated in the eastern Greenland highlands and the GIS is reduced to less than ten per cent of its current volume. Our results narrow the spectrum of possible GIS histories: the longest period of stability of the present ice sheet that is consistent with the measurements is 1.1 million years, assuming that this was preceded by more than 280,000 years of ice-free conditions. Other scenarios, in which Greenland was ice-free during any or all Pleistocene interglacials, may be more realistic. Our observations are incompatible with most existing model simulations that present a continuously existing Pleistocene GIS. Future simulations of the GIS should take into account that Greenland was nearly ice-free for extended periods under Pleistocene climate forcing