January 12, 2018

Fast-moving electrons create current in organic solar cells

Libai Huang, a professor of physical chemistry at Purdue University, in her lab. (Purdue University photo)

Download image

Libai Huang, a professor of physical chemistry at Purdue University, in her lab. (Purdue University photo)

Download image

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — Researchers at Purdue University have identified the mechanism that allows organic solar cells to create a charge, solving a longstanding puzzle in physics, according to a paper published Friday (Jan. 12) in the journal Science Advances.

Organic solar cells are built with soft molecules, while inorganic solar cells, often silicon-based, are built with more rigid materials. Silicon cells currently dominate the industry, but they’re expensive and stiff, while organic cells have the potential to be light, flexible and cheap. The drawback is that creating an electric current in organic cells is much more difficult.

To create an electrical current, two particles, one with a negative charge (electron) and one with a positive charge (electron-hole), must separate despite being bound tightly together. These two particles, which together form an exciton, usually require a manmade interface to separate them. The interface draws the electron through an electron acceptor and leaves the hole behind. Even with the interface in place, the electron and hole are still attracted to each other – there’s another mechanism that helps them separate.

“We discovered that this type of electron-hole interface is not one single static state. The electron and the hole can be far apart or close together, and the farther apart they are, the more likely they are to separate,” said Libai Huang, an assistant professor of chemistry in Purdue’s College of Science, who led the research. “When they’re far apart, they’re actually very mobile, and they can move pretty fast. We think that this kind of fast motion between the positive and negative charge is what’s driving separation at these interfaces.”

Organic solar cells are difficult to study because they’re messy – they look like a bowl of spaghetti, said Huang. There are many interfaces to look at and they’re very small.

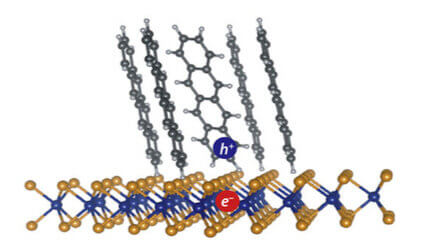

An exciton (electron-hole pair) formed at the interface between tetracene molecules (an organic semiconductor) and single-layer WS2 (an inorganic semiconductor). Dissociation of such interfacial excitons is necessary for the function of organic solar cells. (Image provided)

Download image

An exciton (electron-hole pair) formed at the interface between tetracene molecules (an organic semiconductor) and single-layer WS2 (an inorganic semiconductor). Dissociation of such interfacial excitons is necessary for the function of organic solar cells. (Image provided)

Download image

“It’s really hard to do optical spectroscopy at that length scale. These states also don’t live very long, so you need a time resolution that’s very short,” said Huang. “We developed this tool called ultrafast microscopy in which we combine time and spatial resolution to basically look at processes that happen at fast time scales in very small things.”

Even then, the spatial resolution isn’t good enough, so Huang’s lab created a large, two-dimensional interface to create order in the chaotic arrangement of molecules. The solution to the problem is two-fold, she said: ultrafast microscopy and the interface.

Knowing how excitons separate could help researchers design new interfaces for organic solar cells. It could also mean there are materials to build solar cells with that have yet to be harnessed, said Huang.

Writer: Kayla Zacharias, 765-494-9318, kzachar@purdue.edu

Source: Libai Huang, 765-494-7851, libai-huang@purdue.edu

Note to Journalists: A copy of the paper is available http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/1/eaao3104

ABSTRACT

Highly mobile charge-transfer excitons in two-dimensional WS2/tetracene heterostructures

Tong Zhu, Long Yuan, Yan Zhao, Mingwei Zhou, Yan Wan, Jianguo Mei, Libai Huang

Charge-transfer (CT) excitons at heterointerfaces play a critical role in light to electricity conversion using organic and nanostructured materials. However, how CT excitons migrate at these interfaces is poorly understood. We investigate the formation and transport of CT excitons in two-dimensional WS2/tetracene van der Waals heterostructures. Electron and hole transfer occurs on the time scale of a few picoseconds, and emission of interlayer CT excitons with a binding energy of ~0.3 eV has been observed. Transport of the CT excitons is directly measured by transient absorption micro- scopy, revealing coexistence of delocalized and localized states. Trapping-detrapping dynamics between the delocalized and localized states leads to stretched-exponential photoluminescence decay with an average lifetime of ~2 ns. The delocalized CT excitons are remarkably mobile with a diffusion constant of ~1 cm2 s−1. These highly mobile CT excitons could have important implications in achieving efficient charge separation.