Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

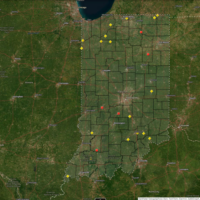

Wild Bulletin, IN DNR, Division of Fish & Wildlife: Epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) is a naturally occurring viral disease commonly seen in the Indiana deer herd. Each year, typically in late summer, Indiana DNR receives reports of deer displaying signs of EHD throughout the state.

This year, DNR confirmed a significant EHD outbreak that began in the northern region of the Hoosier State. In some years, EHD can affect a larger-than-normal portion of the deer and becomes widespread across a county. In those instances, DNR lowers the County Bonus Antlerless Quotas (CBAQs) in the impacted counties to offset the effect of the counties’ EHD outbreak on the deer herd in that region.

EHD is transmitted by biting midges, also known as sand gnats or “no-see-ums.” Deer infected with EHD may display unusual behaviors such as lethargy, excessive salivation, or disorientation. EHD also causes fever in deer, which can cause deer to seek water. As a result, many deer that die from EHD are found in or near open water sources like ponds and rivers. Anyone who finds a deer showing signs of EHD or dead in water is asked to report it at on.IN.gov/sickwildlife.

County bonus antlerless quotas reduced in three counties for 2024-25

Due to the number of reported deer mortalities and extent of EHD in the region, DNR has lowered the County Bonus Antlerless Quotas (CBAQs) in Wabash, Porter, and Allen counties from two bonus antlerless deer to one to help offset the effects of EHD on the deer herd in that region. During the winter, DNR biologists will fully evaluate the effects of EHD and will propose changes to bag limits as required. Hunters can stay informed about CBAQ changes at on.IN.gov/EHD-quotas.

Due to the number of reported deer mortalities and extent of EHD in the region, DNR has lowered the County Bonus Antlerless Quotas (CBAQs) in Wabash, Porter, and Allen counties from two bonus antlerless deer to one to help offset the effects of EHD on the deer herd in that region. During the winter, DNR biologists will fully evaluate the effects of EHD and will propose changes to bag limits as required. Hunters can stay informed about CBAQ changes at on.IN.gov/EHD-quotas.

To find out more view the Indiana Department of Natural Resources EHD Antlerless Bonus Quota Reductions.

Resources:

Be on the Watch for Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD) in Deer, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Report a Sick or Dead Deer, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IN-DNR)

EHD Virus in Deer: How to Detect and Report video, Quality Deer Management Association

Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (pdf), Cornell University

How to Score Your White-Tailed Deer video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Playlist

Deer Harvest Data Collection, Purdue FNR Got Nature? blog

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners: Managing Deer Damage to Young Trees, Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube Channel

Introduction to White-tailed Deer Impacts on Indiana Woodlands, Deer Impact Toolbox, Got Nature? Blog & The Education Store

Purdue Extension Pond and Wildlife Management

Managing White-tailed Deer Impacts on Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

How to Build a Plastic Mesh Deer Exclusion Fence, The Education Store

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Deer Harvest Data Collection, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Handling Harvested Deer Ask an Expert? video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Subscribe to Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources YouTube Channel, Wildlife Playlist

A Woodland Management Moment – Deer Fencing, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Video

Division of Fish and Wildlife, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

MyDNR, Indiana’s Outdoor Newsletter: Help DNR calculate harvest rates. July was dove banding season, when DNR bands mourning doves across the state. This important research effort helps estimate Indiana’s dove population and determine harvest limits for the hunting season. If you recover a banded bird, be sure to report it online. You’ll receive a certificate of appreciation that includes the bird’s information.

Mourning Dove Banding Program

A national banding program was initiated in 2003 to improve our understanding of mourning dove population biology and to help estimate the effect of harvest on mourning dove populations. Doves are banded in July and August in most of the lower 48 states. Band recoveries occur almost exclusively during the U.S. hunting seasons which occur between 1 September and 31 January.

A national banding program was initiated in 2003 to improve our understanding of mourning dove population biology and to help estimate the effect of harvest on mourning dove populations. Doves are banded in July and August in most of the lower 48 states. Band recoveries occur almost exclusively during the U.S. hunting seasons which occur between 1 September and 31 January.

Otis, D.L. 2009. Mourning dove banding needs assessment. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Unpublished report. 22pp.

Mourning Dove Population Status Report Library Collection

Reporting Banded Birds

If you have found or harvested a banded bird, please report it at www.reportband.gov. You’ll need the band number, or numbers, if the bird has more than one band. See below for more information on reward bands. You’ll also need to know where, when and how you recovered the bird. Your contact information will be requested in case there are any questions. The U.S. Geological Survey Bird Banding Lab (BBL) will send you a certificate of appreciation that includes information about the sex, age and species of the bird, and where and when it was banded. You can keep the band. Please note: Even if the band you recover is inscribed with a 1-800 telephone number, as of July 2, 2017, you can only report it at www.reportband.gov.

If some or all of the numbers have worn off, making the band unreadable, please email the BBL at bandreports@usgs.gov or find out on how to send the band for chemical etching. Most bands can be chemically etched so that the numbers can be read. The process does not destroy the band, and it will be returned to you. Thank you for helping conserve and manage migratory birds!

How We Use Banding Data

Managing a complex and mobile resource requires information on breeding and wintering distribution, behavior, migratory routes, survival and reproduction. Biologists gather this information by placing uniquely numbered bands on many species of birds. These birds may be recaptured in the future by biologists, or are found dead by the general public, or in the case of waterfowl or other game birds are harvested by hunters, who then report these bands to the U.S. Geological Survey Bird Banding Laboratory (or Canada’s Bird Banding Office), which provides information about where the bird was banded, where it was recovered, and how long it lived. This is the information that was used to develop the Flyway system that has been used for managing migratory birds since 1950.

The Division of Migratory Bird Management is involved in both the collection and analysis of banding data. Our staff coordinates with banders from various state, federal, private, and tribal agencies in ongoing, annual banding efforts. One example is the Western Canada Cooperative Waterfowl Banding Program (WCCWBP) which focuses on banding waterfowl throughout the Canadian prairies and Canadian boreal forest. Find out more about the program and read the stories of banding crews in the field.

Migratory Bird Program biologists and their counterparts in the U.S. Geological Survey have led the way in developing models that utilize banding and recovery data to predict the impacts of harvest and other take, as well as develop an understanding of environmental factors that drive migratory bird populations. Banding data were instrumental in the development of Adaptive Harvest Management and are used by biologists to set annual waterfowl hunting regulations.

The value of banding data is only fully realized when banded birds are recovered and band numbers reported to the Bird Banding Laboratory. Some recoveries are recaptures (including resighting of bands through spotting scopes) of live birds that are obtained from banders or other wildlife professionals. However, the predominant number of recoveries of dead birds come from the public, either by people who have found birds that have died, or by hunters who have harvested them. More information about how and where to report the recovery of banded birds can be found above under Reporting Banded Birds. We rely heavily upon on your cooperation, and we, and the birds, thank you.

Reward Bands

Harvesting a banded bird is a unique experience. Not only do you get some “jewelry” for your lanyard, but when you report the band, you get a certificate on when and where the bird was banded, and its species, sex and age. Getting a bird with a reward, or “money” band on it is extra special because they are relatively rare. And, oh yeah, the reward check is nice too.

We often get questions about the purpose of these bands. One very important use of banding data is calculating harvest rates. We need to make sure that the harvest of migratory game birds is sustainable, so that bird populations remain healthy, and that the hunting tradition can be continued by future generations. If everyone who harvested a banded bird reported it, the harvest rate would simply be the number of banded birds recovered, divided by the total number banded. However, not everyone reports their band, so we use reward bands to estimate a band reporting rate, which is the likelihood that someone who shoots a banded bird will report it.

Reporting rates can and have changed over time, most notably when a toll-free telephone number was added to the band inscription in the mid-1990s. Prior to that, people had to write a letter to the Bird Banding Lab. By making reporting easier, reporting rates more than doubled (Royle and Garrettson 2005, Boomer et al. 2013, Garrettson et al. 2013, Zimmerman et al. 2009). Now, all band reports must be submitted online (www.reportband.gov.)

Some people falsely believe that if they report a band, it could lead to more restrictive hunting regulations. In fact, the more band reports we get, the more confident we can be of our data, and this allows us to set seasons that allow more harvest opportunity, while ensuring that the harvest is sustainable.

We encourage you to report all your bands at www.reportband.gov. If you get a bird with a reward band, it should also have a second, standard band on it. Please report both bands. Occasionally, bands get worn and are lost, so if your bird only has a reward band, please report it. Someone will contact you to help you complete the report so that you can get your certificate and check.

Read the full article at Bird Banding: A Conservation Tool within the Migratory Bird Program.

To subscribe to the newsletter visit MyDNR Email Newsletter.

Resources

Learn how forests are used by birds new videos, Got Nature? Blog

Managing Woodlands for Birds, The Education Store-Purdue Extension resource center

Climate Change + Birds, Purdue Institue for Sustainable Future

National Audubon Society

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Forestry for the Birds, The Nature Conservancy YouTube Channel

Breeding Birds and Forest Management: the Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment and the Central Hardwoods Region, The Education Store, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Forest Birds, The Education Store

Managing Woodlands for Birds, The Education Store

Managing Woodlands for Birds Video, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Breeding Birds and Forest Management: the Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment and the Central Hardwoods Region, The Education Store

The Birders’ Dozen, Profile: Baltimore Oriole, Indiana Woodland Steward

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

MyDNR, Indiana’s Outdoor Newsletter: Every May, wild turkey chicks (poults) begin to hatch in Indiana, and DNR needs your help counting turkey broods (hens with poults) and hens without poults.

Brood reports have been collected every year since 1993 to calculate the annual Wild Turkey Production index, which informs biologists about population status and guides management decisions for the species. Please share your 2024 observations with us online from July 1 until Aug. 31. Recording observations takes less than five minutes, and no login is required.

In 2023, DNR received more than 2,203 reports across all 92 counties in Indiana, and we’re hoping for even more this year. Our goal is to receive 3,000 total observations with at least 25 per county.

Why count turkeys?

Brood surveys provide useful estimates about annual production by wild turkey hens and the survival of poults (young turkeys) through the summer brood-rearing period. Summer brood survival is generally the primary factor influencing wild turkey population trends. Information on summer brood survival is essential for sound turkey management. Information gathered through the brood survey includes:

- Average brood sizes (hens + poults). For example, in the photo above there is one hen with seven poults, for a brood size of eight.

- Percentage of adult hens with poults.

- Production Index (PI) = total number of poults/total number of adult hens

What is a wild turkey brood?

A wild turkey brood is composed of at least one adult hen with young (poults). As the summer progresses, multiple broods may gather into what is termed a “gang” brood with several adult hens and multiple broods of poults of varied ages. During summer, adult gobblers (male turkeys) play no role in raising a brood and either form small male only “bachelor” flocks or are observed as a single gobbler.

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources – Department of Fish and Wildlife rely on your observations to calculate their Production Index, so every report counts! Indiana DNR appreciates your participation.

Jarred Brooke, extension wildlife specialist with Purdue Forestry & Natural Resources, shares how you can participate in the Indiana Department of Natural Resources’ annual turkey brood survey in a quick video.

To learn more, visit DNR: Turkey Brood Reporting.

To subscribe to the newsletter visit MyDNR Email Newsletter.

Resources:

Four Simple Steps, Help Indiana DNR Estimate Wild Turkey Populations, Purdue Extension – Forestry & Natural Resources

Truths and Myths about Wild Turkey, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Wildlife, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Turkey Brood Reporting, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Wild Turkey, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Wild Turkey Hunting Biology and Management, Indian Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Subscribe to Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources YouTube Channel, Wildlife Playlist

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Purdue Landscape Report: Spring is always a wonderful, if somewhat chaotic, time of year in Indiana. Between the heavy rains and beautiful flowers blooming, the months leading up to summer can make your head spin. While we enjoy the trees greening out and watch out for storms, we need to be aware that spring awakens other organisms, many of which have a major impact on our lives. This time of the year introduces a host of insect species hatching from eggs, emerging from cocoons, or returning from their overwintering nap, and many of those species mean bad news for our trees. One of the most impactful species we deal with in Indiana is Lymantria dispar, or the spongy moth.

The spongy moth, so named for the sponge-like egg masses they lay in the early fall, is an invasive species belonging to family Erebidae, a large group of moths that include species such as the woolly bear we see every year in Indiana. Spongy moth is a native to Eurasia, and historical record shows it has caused problems throughout Europe as early as the seventeenth century. In the late nineteenth century, an amateur entomologist and would-be entrepreneur brought spongy moth to North America in a failed attempt to create a new silk moth hybrid. Inevitably, the insect escaped captivity and has since spread through several states over the last century, including the northern portion of Indiana.

Spongy moth is a generalist pest that strips leaf tissue from many species of trees, though it has a particular preference for oak. Like all butterflies and moths, the larva, or caterpillar, is the damaging form of this insect. Spongy moth caterpillars bear chewing mouthparts they use to consume leaf tissue, but they do not attack wood or root systems of their hosts. Adults are non-feeding and only survive long enough to reproduce. Spongy moth can produce large populations each year and move quickly across a landscape, creating sudden infestations and near-complete defoliation in those areas. While trees will typically recover after losing a significant portion of their leaf tissue, repeated infestations will make a host tree more susceptible to disease, reduce resilience, and potentially lead to death.

Like other moths and butterflies, spongy moth has well-defined life stages that can be used to easily identify them. Caterpillars will begin to appear between mid-April and early May and can be identified by their hairy appearance, distinct black, blue, and red coloration, and the tendency to move up and down the surface of a tree (Fig. 1). Male larvae will develop through five instars, while female larvae will grow over the course of six instars. Larvae will enter the pupal stage midsummer and spend approximately ten to twelve days developing. The pupae of this insect are darkly colored and lack the silk cocoon seen in other species. Adult male moths will emerge in the latter half of the summer season, followed by female moths about a week later. The moths can be identified by the pattern on their wings: a black chevron associated with a dot on a pale white or cream background (Fig. 2). Male moths will have large, feathery antennae and are capable of flight, while females are flightless with smaller antennae. Adult moths will only survive for a few days to reproduce and lay sponge-like egg masses, which will overwinter and hatch the following spring (Fig. 3).

Management of spongy moth often involves work by state and federal agencies, such as the Indiana’s Department of Natural Resources. Within the Hoosier state, the DNR has quarantined several northern counties to prevent movement of materials that could potentially spread spongy moth even further. They also conduct yearly mitigation programs to eliminate infestations that are outside of the quarantined area. Indiana DNR, specifically the Division of Entomology and Plant Pathology, posts information on all mitigation efforts as well as hosts public meetings so residents understand what treatments are used for spongy moth management, and how it will affect their community.

Most organizations, including Indiana DNR, typically use two methods to control spongy moth: mating disruption and Btk applications. Mating disruption uses the moth’s biology against it by confounding its ability to locate a mate. Spongy moths, like many species, use a chemical signal called a pheromone to attract potential mates; male moths follow the trail of pheromones emitted by a female. By filling an area with the pheromone, the male moths become unable to follow individual chemical signals, resulting in fewer eggs being laid for the next spring. Pheromones are also highly species-specific, ensuring little to no impact on other organisms. In Indiana, the chemical used for mating disruption is applied aerially to cover a significant area, and the chemical used is made of food grade materials that break down easily.

Btk applications are also done aerially, coating foliage with a selective pesticide that only affects moth and butterfly species. Btk is a protein derived from a native soil-borne bacteria (Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki) and works by damaging the internal lining of an insect’s gut after being consumed. This is a pesticide that is commonly applied to all manner of crops, persists only for a short time in the environment, and only harms insects. It also has the benefit of having minimal impact on pollinators, especially when applied using label directions.

While spongy moth is a serious challenge, there are some options you can use to protect your natural spaces. The first option, and perhaps the most important, is to be vigilant. If you live in or near an infestation, get into the habit of checking your trees for egg masses starting in the late summer through the fall. When you find egg masses, check for small pinholes in the sponge-like covering; the hole is created by a beneficial parasitoid wasp that uses the caterpillars as hosts for their young. You can also destroy egg masses by using a horticultural oil labeled for that purpose, or by scraping off the egg masses into a bucket of soapy water. Also be watchful of egg masses being laid on homes, firewood, or the sides and undersides of vehicles that move through infested areas.

Larvae will begin to appear in late April, with warmer temperatures encouraging populations to hatch earlier. One method of controlling larvae is to use burlap banding as a trap to capture larvae moving up and down the surface of the tree trunk. This can be done by tying a folded piece of burlap around the trunk of the tree at approximately chest height. Caterpillars, attempting to hide from predators during the day, will crawl into the folds. Once the late afternoon arrives, the caterpillars can be removed and destroyed by dumping them into soapy water. You can also use sticky substances in an effort to capture the caterpillars by coating a tree at chest height with it, but this method has several drawbacks. Any substrate that is sticky enough to capture spongy moth caterpillars will also capture any other insect, beneficial and damaging, and could potentially catch small mammals and birds as well.

If you plan to use pesticides, May through June is the best time to apply. Biological pesticides such as Btk, spinosad, and others, are available for homeowner use, as well as systemic insecticides such as dinotefuran and emamectin benzoate. However, given how widespread the caterpillars can be and the heights they can reach, using some insecticides may not be feasible or may require professional assistance. Homeowners and property managers should consult certified arborists to learn what options will be best, and use pesticides as per the label directions.

While spongy moth is now a permanent part of our ecosystem, we still want to limit its ability to move into new parts of Indiana. If you live outside of quarantine areas and find an egg mass, caterpillar, or adult moth, report them by contacting the Indiana Department of Natural Resources at 1-866-NOEXOTIC, or by emailing DEPP@dnr.in.gov; make sure to include pictures and location. You can also consult your local Extension office for assistance in finding arborists, speaking with specialists, or getting problem insects identified.

Original article posted: Purdue Landscape Report.

Subscribe and receive the newsletter: Purdue Landscape Report Newsletter.

Resources:

Spongy Moth, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

The Spongy Moth in Indiana, Purdue Extension – Entomology

Invasive Species, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Invasive Species

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Pest Management, The Education Store

Protecting Pollinators: Why Should We Care About Pollinators?, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Subscribe Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Bob Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Educator

Purdue Entomology

MyDNR, Indiana’s Outdoor Newsletter: Indiana DNR has confirmed the state’s first positive case of chronic wasting disease (CWD) in LaGrange County. CWD is a fatal infectious disease, caused by a misfolded prion, that affects the nervous system in white-tailed deer. It can spread from deer-to-deer contact, bodily fluids, or through contaminated environments.

There have been no reported cases of CWD infection in people, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that hunters strongly consider having deer tested before eating the meat. The CDC also recommends not eating meat from an animal that tests positive for CWD.

CWD has been detected in 33 states including the four bordering Indiana (Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, and Kentucky). Because CWD had been detected in Michigan near the Indiana border, a detection in LaGrange County was likely.

If you see any sick or dead wildlife, deer or otherwise, please report your observations on the DNR: Sick or Dead Wildlife Reporting page.

For more information visit DNR: Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD).

To subscribe to the newsletter visit MyDNR Email Newsletter.

Resources:

Chronic Wasting Disease, USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS)

Bovine Tuberculosis in Wild White-tailed Deer, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Hunting & Trapping, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR)

Designing Hardwood Tree Plantings for Wildlife , The Education Store

Wildlife Habitat Hint: Trail Camera Tips and Tricks, Got Nature? Blog

How to Score Your White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

White-Tailed Deer Post Harvest Collection, video, The Education Store

Age Determination in White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

How to Build a Plastic Mesh Deer Exclusion Fence, The Education Store

Ask the Expert: Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment – Birds and Salamander Research, Purdue Extension – FNR

A Template for Your Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Deer Impact Toolbox, Got Nature? blog, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR)

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Purdue Landscape Report: It’s that time of year when we remind everyone to watch for spotted lanternfly (SLF) infestations. Spotted lanternfly is an invasive insect first detected in Pennsylvania in 2014, and has since spread throughout the eastern USA. Its preferred host is the invasive Tree-of-Heaven, but it also feeds on a wide range of important plant species, including grapes, walnuts, maples, and willows.

There are two known populations of SLF in Indiana. The first population was found in 2021 in Switzerland County, and the second population was found in Huntington County in 2022. The Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR), Division of Entomology and Plant Pathology, has launched a delimiting survey throughout the two counties to delimit its range and monitor for activity.

Egg hatch was confirmed in Huntington County and Switzerland County in mid-May at the two known sites. A few adults have been caught about one mile south of the core infestation site in Huntington; however, there are not any new infestations reported as of July 2023. IDNR employees have completed several egg scraping events at the infestation sites, removing over 16,800 egg masses so far this year. That’s over 672,000 eggs!

Finding this invasive insect early is crucial to preventing its spread as long as possible. Currently, SLF nymphs are in their 1st-3rd instar, so watch for small, black, white-spotted bugs on Tree-of-Heaven. Later instars are black and red with white spots. The adults are about 1 inch long, with very brightly colored wings. The forewings are light brown with black spots, and the underwings are a striking red and black, with white band in between the red and black. When at rest, the adult SLFs appear light pinkish-grey.

Report any suspect findings at https://ag.purdue.edu/reportinvasive/

To view this full article and other Purdue Landscape Report articles, please visit Purdue Landscape Report.

Subscribe and receive the newsletter: Purdue Landscape Report Newsletter.

Resources:

The Purdue Landscape Report

Spotted Lanternfly, Indiana Department of Natural Resources Entomology

Spotted Lanternfly Found in Indiana, Purdue Landscape Report

Invasive plants: impact on environment and people, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Woodland Management Moment: Invasive Species Control Process, Video, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Invasive Species, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Report Invasive, Purdue College of Agriculture – Entomology

Alicia Kelley, Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey (CAPS) Coordinator

Purdue Extension – Entomology

Purdue Landscape Report: I think white pines are beautiful trees, especially at maturity, and they have the added advantage that they are one of the few conifers that don’t try to kill you with their needles. Besides working with the foliage, have you ever had to “rescue” a child who climbed too high in a spike-infested deathtrap of an evergreen? Did you develop the rashes to prove it? Not with a white pine!

My kids haven’t had the chance to climb a mature white pine. Many seem to decline at about 15-20ft. We have been describing this issue as white pine decline, but it isn’t entirely easy to explain. There are a number of factors that influence overall plant health and that can contribute to plant decline, but let’s focus on white pines here. White pine decline is typically attributed to root stress that can be caused by or exacerbated by high soil pH (chemically unavailable nutrients), heavy soil texture (clays), compaction, and excessive soil moisture.

Anything that affects the roots can affect the overall health of the tree, so if the roots are compromised and they cannot uptake water or nutrients, the tree will decline due to lack of nutrients or even lack of water. Needles on an affected tree will turn yellow and eventually brown and fall off prematurely (Figure 1). A symptom of white pine decline includes stems that have shriveled or desiccated bark because roots are not functioning properly and cannot pull in enough water (Figure 2).

Depending on the severity of the root conditions, trees may take several years to decline and die, but with significant root stress, trees will decline faster. I have been seeing a lot of white pine yellowing around West Lafayette and in Indianapolis over the last year and a half and I think the odd environmental extremes have not been helping. Cycling between prolonged drought and torrential downpours lead to stress that can have lasting effects that could take years to recover from, or might be the final nail in the coffin.

There is nothing that can be done to recover from or stop decline once symptoms are observed in white pine. However, taking an approach to actively mitigate stress can help extend the life of white pine trees that are currently healthy. In many cases, one white pine will decline while other trees in the vicinity appear healthy (Fig 3, 4). Removal of symptomatic trees is important because stressed trees often attract bark beetles which can spread to the remaining healthy trees.

Another point: not every tree is going to respond the same way at the same location. Stress factors, such as a poor root system when planted, planting too deeply, or even Phytophthora root rot may have predisposed one tree to decline more than others. Just because one tree goes down doesn’t mean they all will, so keep an eye on the others and try to improve the site conditions where practical.

To view this full article and other Purdue Landscape Report articles, please visit Purdue Landscape Report.

Subscribe and receive the newsletter: Purdue Landscape Report Newsletter.

Resources:

Root Rot in Landscape Plants, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Dead Man’s Fingers, Purdue Landscape Report

ID That Tree Fall Color: Sugar Maple, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

ID That Tree Fall Color Edition: Black Gum, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana, The Education Store

Autumn Highlights Tour – South Campus, Purdue Arboretum Explorer

Subscribe, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Tree Defect Identification, The Education Store

Tree Wound and Healing, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Ask an Expert: Tree Selection and Planting, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube playlist

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube playlist

Invasive Species, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Invasive Species

Find an Arborist, International Society of Arboriculture

John Bonkowski, Plant Disease Diagnostician

Departments of Botany & Plant Pathology

Wild Bulletin, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Fish and Wildlife: March is the beginning of peak nesting season for Indiana’s state-endangered trumpeter swan. During the nesting season, it is possible to see trumpeter swans in the northern third of the state, especially Lake, Laporte, Kosciusko, LaGrange, Noble, Steuben, and St. Joseph counties, where they have ample habitat. Hunted to near extinction in the 1900s, the species has made great strides in population numbers, largely due to the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Large, open bodies of shallow water with abundant aquatic plants are the preferred habitat of trumpeter swans, and there is potential to see the number of trumpeters increase in northern Indiana; however, the species’ recovery in Indiana isn’t out of the water yet.

Lake, Laporte, Kosciusko, LaGrange, Noble, Steuben, and St. Joseph counties, where they have ample habitat. Hunted to near extinction in the 1900s, the species has made great strides in population numbers, largely due to the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Large, open bodies of shallow water with abundant aquatic plants are the preferred habitat of trumpeter swans, and there is potential to see the number of trumpeters increase in northern Indiana; however, the species’ recovery in Indiana isn’t out of the water yet.

Loss of habitat is the No. 1 reason for species decline across the globe, with the presence of invasive species being the second largest reason. Invasive mute swans throughout Indiana pose a threat to trumpeter swans. Mute swans are an aggressive bird that can negatively impact trumpeter swans through direct killing of adults and their young, outcompeting them for available nesting spaces, and destroying the vegetation on our bodies of water. Managing mute swans has been shown to be an effective method for increasing trumpeter swans in other states.

Use these helpful tips to distinguish between the native trumpeter swan and the invasive mute swan:

- Trumpeter swans have black bills and legs. Mute swans have orange bills with black knobs.

- Trumpeter swans hold their necks straight when swimming in water and flying. Mute swans hold their necks in an “S” shape.

- Trumpeter swan numbers increase in winter in southwest Indiana and in the spring can be more common in the northern third of Indiana. Mute swans can occur statewide but are more common in the north.

Learn more about our endangered wildlife or find more information on mute swan management on our website.

To learn more about mute swans and their impact, please visit Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Mute Swans.

Resources:

Managing Woodlands for Birds Video, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Breeding Birds and Forest Management: the Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment and the Central Hardwoods Region, The Education Store

The Birders’ Dozen, Profile: Baltimore Oriole, Indiana Woodland Steward

Ask An Expert, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

It’s For the Birds, Indiana Yard and Garden-Purdue Consumer Horticulture

Birds and Residential Window Strikes: Tips for Prevention, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

No Room at the Inn: Suburban Backyards and Migratory Birds, Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment – Wildlife Responses to Timber Harvesting, The Education Store

Subscribe, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Hunting and Trapping Guide, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Wild Bulletin, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Fish and Wildlife: Our latest Fishing Guide features women anglers, responsible fishing practices, a delicious French-style walleye recipe, and the regulations you need for having a successful day fishing in Indiana’s waters.

waters.

You can find the free guide online or pick up a hard copy at your local license retailer.

This guide provides a summary of Indiana fishing regulations. These regulations apply only to fish that originate from or are taken from Indiana’s public waters. Fish from public waters that migrate into or from private waters are still covered by these regulations. These regulations do not apply to fish in private waters that did not originate from public waters.

This guide is not intended to be a complete digest of regulations. If you need complete versions of Indiana rules and regulations for fishing, they can be found in Indiana Code or in Indiana Administrative Code Title 312.

To view this new guide, please visit Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Fishing Guide & Regulations.

Resources:

Hybrid Striped Bass Farmed Fish Fact Sheet, The Education Store

Largemouth Bass Farmed Fish Fact Sheet, The Education Store

Seafood Basics: A Toolkit for Understanding Seafood, Nutrition, Safety and Preparation, and Sourcing, The Education Store

Walleye Farmed Fish Fact Sheet, The Education Store

Rainbow Trout Farmed Fish Fact Sheet, The Education Store

A Guide to Small-Scale Fish Processing Using Local Kitchen Facilities, The Education Store

Aquaculture Family Coloring Book Development, The Education Store

Eat Midwest Fish, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant online resource hub

Subscribe to Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources YouTube Channel, Wildlife Playlist

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Fish from left to right: Threadfin Shad, Gizzard Shad, Skipjack Herring, Silver Carp (invasive carp), and Goldeye.

Wild Bulletin, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Fish and Wildlife: Spring is the time anglers return to fishing on Indiana’s lakes and rivers. Often that includes catching and using live bait. Remember to dispose of all unused bait fish properly in the trash, as invasive carp could be lurking in your bait bucket. Improperly disposing of unused bait fish in a lake or stream could potentially allow invasive species, like silver carp, to spread in Indiana waters.

Invasive carp are a select group of cyprinid fishes (minnow family) that are native to Asia. The term “invasive carp,” formerly known as “Asian carp,” collectively refers to bighead carp, silver carp, grass carp, and black carp. Each of these species was intentionally introduced into the United States for different purposes; however, all are now considered invasive nationally and in Indiana. Invasive carp compete with native species and pose a threat to Indiana’s aquatic ecosystems.

Find out more about how you can help in the fight against invasive carp at DNR: Fish & Wildlife Resources.

Resources:

Asian Carp | Purdue University Report Invasive Species

Question: Aren’t There Concerns About Consuming Asian Carp As A Food Source In Indiana Streams?

Invasive Species, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Invasive Species

Walleye Farmed Fish Fact Sheet, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Yellow Perch Farmed Fish Fact Sheet, The Education Store

A Guide to Small-Scale Fish Processing Using Local Kitchen Facilities, The Education Store

Eat Midwest Fish, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant online resource hub

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Recent Posts

- IN DNR Deer Updates – Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Detected in Several Areas in Indiana

Posted: October 16, 2024 in Alert, Disease, Forestry, How To, Wildlife, Woodlands - Flying Into July: Bird Banding Season Begins – MyDNR

Posted: August 6, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, Wildlife - 2024 Turkey Brood Count Wants your Observations – MyDNR

Posted: June 28, 2024 in Alert, Community Development, Wildlife - Spongy Moth in Spring Time – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: June 3, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, How To, Invasive Insects, Urban Forestry - MyDNR – First positive case of chronic wasting disease in Indiana

Posted: April 29, 2024 in Alert, Disease, How To, Safety, Wildlife - Report Spotted Lanternfly – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: April 10, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, Invasive Insects, Plants, Wildlife, Woodlands - Declining Pines of the White Variety – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: in Alert, Disease, Forestry, Plants, Wildlife, Woodlands - Are you seeing nests of our state endangered swan? – Wild Bulletin

Posted: April 9, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, How To, Wildlife - 2024-25 Fishing Guide now available – Wild Bulletin

Posted: April 4, 2024 in Alert, Aquaculture/Fish, Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, How To, Ponds, Wildlife - Look Out for Invasive Carp in Your Bait Bucket – Wild Bulletin

Posted: March 31, 2024 in Alert, Aquaculture/Fish, Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, Invasive Animal Species, Wildlife

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands