Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

Tribune-Star: Both my son and daughter raised rabbits as members of 4-H, so for years our barn served as a makeshift hutch, complete with wire cages, watering and feeding bowls, and fur — lots of fur, some still sticking to the old building’s dusty rafters all this time later.

My brother and sister and I also grew up with rabbits, although it was through the likes of immortal “Bugs Bunny” features, such as “The Rabbit of Seville” (yes, with Bugs massaging Elmer Fudd’s head to the music of Rossini) and “14 Karat Rabbit” (featuring a greedy gold mining “Yosemite Sam”). I plan to share those cartoons with my grandsons, and sure hope they have the opportunity to watch them as we did: on a Saturday morning; not fully dressed; with few cares in the world; preferably, a bowl of cereal in hand.

and “14 Karat Rabbit” (featuring a greedy gold mining “Yosemite Sam”). I plan to share those cartoons with my grandsons, and sure hope they have the opportunity to watch them as we did: on a Saturday morning; not fully dressed; with few cares in the world; preferably, a bowl of cereal in hand.

That being said, I have no predisposed dislike of rabbits at all. But this summer has tested my patience as far as the Eastern Cottontail is concerned; they’ve invaded my property in record numbers. I have never seen so many rabbits short of a show at the fairgrounds, not even in my more innocent Warner Brothers days.

They seem to be everywhere: peeking out from beneath my car when I walk out the door; startled from a flower bed or garden when I reach for a weed to pull; nibbling about in our yard as we watch from our windows in the evenings. Some of them hardly even move now when I show up; I honestly think I could get them to eat out of my hand.

I don’t think our infestation approaches what’s happened in Australia. According to a 2020 “National Geographic” article, European rabbits were introduced to the continent in 1859 (I also read 1788 in another story) so they could be hunted; just 13 were originally brought in. By the turn of the century, the rabbits constituted one of the greatest invasive threats any country has ever experienced. They destroyed crops at prodigious rates, caused erosion, and nearly restructured the continent’s biodiversity. Fences, poisons, traps, even the use of rabbit-sensitive pathogens were used to try to control them; it’s estimated — despite doubled-down efforts with new pathogens — that there are over 200 million feral rabbits there now.

In a summer that has already been a bit out of whack, I have lately begun to wonder if it’s just me, or are there others seeing an uptick in rabbit populations too? And, before I take this any further, I’ll say that I am ruling out eliminating our problem with a shotgun, let alone pathogens. Just a few trips decades ago with a hardcore-hunting grandfather ended my ambitions for putting rabbits on our supper table; I tend to live and let live, and, of course, complain.

Not only did the furry little vandals eat all of the swamp milkweed I was growing for our monarch butterflies, they have gnawed off sunflowers — both planted and volunteer — and have, in particular, eaten many of our late-blooming hostas (nearly ready to flower) that must be particularly tender and tasty.

Purdue University Extension Specialist Jarred Brooke says, “I have received reports of abundant rabbits around the state. There are likely several causes for this, but it is hard to pin down the exact causes. Cottontail populations tend to be cyclical … One year the population may be booming, and then the next you might not see many. And it’s really hard to predict when those cycles will occur.”

Brooke says that things like mild winters — which we have luckily had these past few years — allow cottontails to breed earlier and more often, bring on lush green vegetation, and often allow predators to choose from a more varied menu than in summers following harsh winters.

“It’s hard to say exactly what is going on this year, but it sounds like we are in the increasing phase of their cycle, which is normal, “Brooke says. “Adding in the fact that many cottontail predators in some areas had an easy meal this spring with cicadas certainly doesn’t hurt. With that said, I don’t know any research that has linked rabbit populations with cicadas, but cicadas have been linked to population increases in other mammals, turkeys and songbirds.”

Brian McGowan, Certified Wildlife Biologist through Purdue University’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, says it’s nearly impossible to tell when we are having a big rabbit year: “Methods like roadkill surveys or bow hunter surveys provide some information, as well as annual harvest; however, these and other methods have a time lag element to them where they are done once a year and the data is not always immediately analyzed.”

Resources:

Wildlife Habitat Hint, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube channel

Considerations for Trapping Nuisance Wildlife with Box Traps, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Preventing Wildlife Damage – Do You Need a Permit? – The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Selecting a Nuisance Wildlife Control Professional, The Education Store

How to Construct a Scent Station, Youtube

Question: How do I properly relocate raccoons from my attic?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension FNR

Jarred Brooke, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

Brian MacGowan, Extension Wildlife Specialist

Department of Forestry & Natural Resources, Purdue University

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Resources:

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources Youtube Channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR Youtube Channel

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, Purdue University Press

Native Trees of the Midwest, Purdue University Press

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Yellowwood, The Purdue Arboretum Explorer

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

In this episode of A Woodland Management Moment, Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee talks about a variety of hand tools you can use to assist with invasive species control and timber stand improvement on your property if you choose not to use power tools.

If you have any questions regarding trees, forests, wildlife, wood products or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Resources:

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, Purdue University Press

Native Trees of the Midwest, Purdue University Press

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners Video Series, Playlist, Indiana Department of Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Image 1. Cicada damage is typically restricted to the small, outer twigs. Trees may be completely covered by cicadas or have a few isolated dead twigs. All trees in these images are expected to suffer no serious long term effects from this damage. Images by Clifford Sadof of Purdue University and Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources – Forestry.

Purdue Landscape Report: Dead leaves covering trees (image 1) or on the ground beneath them (image 2) in July would normally be a worrying sign for tree health, but this year much of the damage can be blamed on 17-year cicadas. This damage is unlikely to cause serious trouble for healthy, large trees and management is relatively simple. The choice to prune or not to prune comes down to cost, aesthetics, and concern for the next generation of cicadas.

How Cicadas Damage Plants

Cicada damage is similar to a light pruning and should not be an issue for healthy, mature trees. Cicadas damage trees when they lay their eggs in small twigs (3/16 to 1/2 inch in diameter) on deciduous trees and shrubs. They have a long, thin body part called an ovipositor that resembles a sewing needle that they stab into plants to lay their eggs. This action creates small holes and cracks in the bark (image 3). If enough cicadas lay their eggs in a twig, it can damage the bark enough to kill the twig (image 1).

Image 2. The dead twigs killed by cicada egg laying may break off the tree and litter the ground underneath. Image by Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources – Forestry.

Recognizing Cicada Damage

The degree of cicada damage depends on insect density and the number of trees in the area. To determine if a tree or bush has been damaged by cicadas, ask the following questions:

Image 3. Cicada egg laying damage varies between tree species, but is consistently in a straight, length-wise line along the branch. Note that all four examples also have signs of either puncture marks, cracks in the bark, or some combination of the two. Images by John Ghent, Clifford Sadof of Purdue University, Tim Tigner of Virginia Department of Forestry, and Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources – Forestry.

1. Were there 17-year cicadas within 50 meters (~164 ft) of the tree this year? Cicadas do not travel very far. If there weren’t noticeable numbers of 17-year cicadas nearby the damage was likely caused by something else.

2. Is the damage on a deciduous tree or bush? Cicadas rarely lay their eggs on evergreen trees and herbaceous plants. Damage on these types of plants is likely caused by something other than the cicadas.

3. What size of branches and twigs are damaged? Cicadas show a strong preference for small twigs (3/16 to 1/2 inch in diameter). As a result, damaged trees may appear as though their outer layer of leaves is dead while the inner leaves remain healthy (image 2). If larger branches are dead, the damage was probably not caused by cicadas.

4. Does the bark have typical egg laying damage? If you can reach the damaged twigs, look for a row of puncture wounds often connected by cracks length-wise along the branch. Their appearance may vary between tree species (image 3), but they will almost always be length-wise.

Resources:

Billions of Cicadas Are Coming This Spring; What Does That Mean for Wildlife?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR)

17 Ways to Make the Most of the 17-year Cicada Emergence, Purdue College of Agriculture

Ask an Expert: Cicada Emergence Video, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension-FNR

Periodical Cicada in Indiana, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Cicada Killers, The Education Store

Cicada, Youth and Entomology, Purdue Extension

Purdue Cicada Tracker, Purdue Extension-Master Gardener Program

Purdue Landscape Report

Elizabeth Barnes, Exotic Forest Pest Educator

Purdue University Department of Entomology

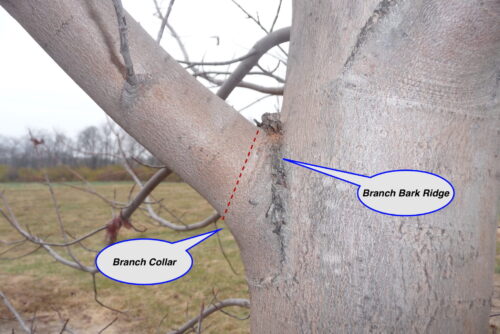

Purdue Landscape Report: Pruning is an important maintenance practice on trees that is discussed a great deal. An essential part of making the pruning cut properly is the ability to identify the parts of a branch. Identification of the branch bark ridge and branch collar are vital to severing the branch in a place that facilitates fast and effective wound closure, reducing decay in the location of the cut.

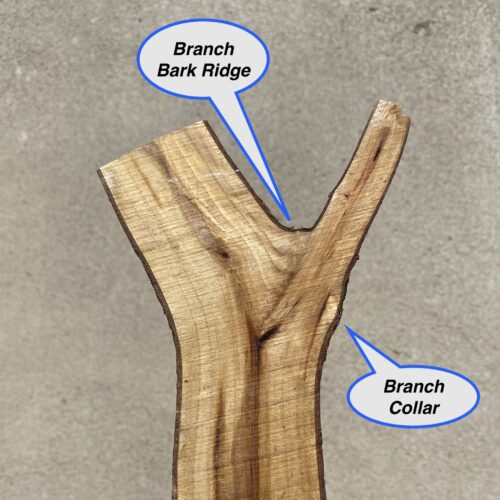

Branches on trees arise from lateral buds present in leaf axils. Initially, lateral shoots (branches) grow in length and diameter at approximately the same rate as the parent stem. As branches become shaded naturally by crown expansion, photosynthesis is reduced in that location and growth slows to a lesser rate than the parent or main stem. A swollen area or collar develops at the junction of branch and stem because of their differential growth rates and by the intermingling of vascular tissues from both the branch and the stem or trunk.

This swollen area is commonly referred to as a branch collar and often present in many branches on the underside of the branch. This specialized location on the branch is composed of trunk (parent stem) wood. The branch collar contains a protective chemical zone that inhibits the movement of decay organisms from dead or dying branches into healthy tissues of the parent stem. As branches begin to die from shading, pests or storm damage, for examples, they usually are walled off (compartmentalized) by tissues in the branch collar which prevents movement of decay organisms into the parent stem.

Identify the branch collar and branch bark ridge to perform a good cut, which is just outside the line.

Another important branch component to identify in tree branches is the branch bark ridge. This part of the attachment is composed of rough, usually darkened, raised bark formed at the union where the branch meets the parent stem. The ridge extends from the top of the branch down both sides of the branch union. Together with the branch collar, the portion of the ridge pushed up in the union provides our target for the pruning cut. The BBR is present on every branch union and is an important identifying feature for determining tool placement.

An internal view of the branch collar and branch bark ridge revealing the intermingled stem and branch wood fiber.

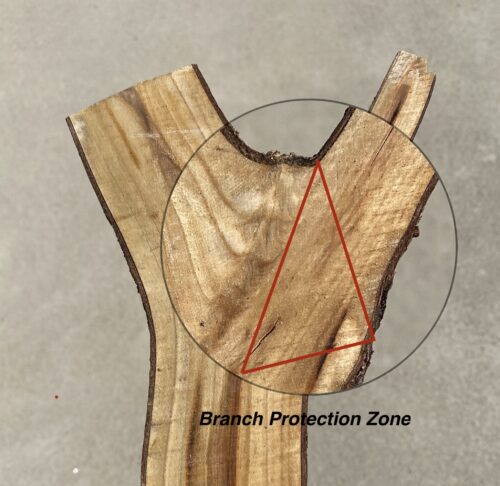

The combination of the branch collar, branch bark ridge, and the overlap between the branch and stem are the branch components that form what is called the branch protection zone. This zone contains specialized chemical compounds that help resist the spread of disease in the tree and facilitate wound-sealing. Always avoid damaging the area within the branch collar and branch bark ridge to help the tree recover from the pruning cut as quickly as possible.

The Branch Protection Zone is an area that contains specialized chemicals to assist with the healing process after pruning.

For the best advice on tree maintenance and care, seek out a tree care professional with the experience and expertise to care for your trees. Search for a tree care provider in your area. Also, consider hiring an ISA Certified Arborist which can be found here.

Resources:

Planting Your Tree Part 1: Choosing Your Tree, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Tree Planting Part 2: Planting a Tree, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Tree Selection for the “Un-natural” Environment, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

Tree Pruning Essentials Video, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Purdue Landscape Report

Lindsey Purcell, Urban Forestry Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue Landscape Report: While fungi are responsible for many of our foliar disease problems, different fungal pathogens present as problems throughout the country, depending upon the host plant grown and the environmental conditions. This is a brief overview of several common types of fungal leaf diseases that occur in Indiana and throughout North America (and Europe). Recognizing the symptoms and signs is an important first step to diagnose a disease problem, followed by how to manage these diseases by combining cultural and chemical controls.

Common fungal leaf diseases of deciduous trees and shrubs

Anthracnose. Anthracnose diseases probably are the best-known foliar fungal diseases of deciduous trees. They affect many ornamental trees including major shade-tree genera such as sycamore (Platanus spp.), oak (Quercus spp.), maple (Acer spp.), elm (Ulmus spp.) and ash (Fraxinus spp.) (Fig. 1). Anthracnose actually is a general term describing symptoms such as dead irregular areas that form along and between the main vein of the leaf. The leaves may also become curled and distorted and twigs may die back. The fungus overwinters in infected twigs and the petioles of fallen leaves, and the spores disseminate in the spring by wind and splashing rain. The disease, while unsightly, rarely results in the tree’s death. Sycamores and other trees often withstand many years of partial defoliation. However, one anthracnose disease is more serious. Dogwood anthracnose (Discula destructiva) is a devastating problem on the Eastern seaboard, but has not been a significant issue here in Indiana.

Leaf blisters result in the blistering, curling and puckering of leaf tissue. Oak leaf blister (Taphrina caerulescens) is a common blister disease of oaks (Fig. 2)., particularly the red oak subgenus, which includes Northern red oak (Q. rubra) and pin oak (Q. palustris) among others. The symptoms begin as a slight yellowing of the infected leaf followed by round, raised blisters. These turn brown, and the infected leaves fall prematurely. This fungus overwinters as spores on the buds.

Leaf spot is a general symptom caused by a multitude of pathogens and infect all deciduous trees and shrubs, and include dead spots with a defined boundary between living and dead tissue. The dead tissue often separates from the surrounding living tissue creating a “shot-hole” appearance on the infected leaves. Common hosts include dogwood, maples, hydrangea, rose, holly, and Indian-hawthorn.

Tar spot (Rhytisma spp.) is a leaf disease with initial symptoms similar to leaf spot. The disease is most common on red (Acer rubrum) and silver maple (A. saccharinum) (Fig.3), but it can occur on a wide range of maple species from sugar (A. saccharum) and Norway (A. platanoides) to bigleaf maple (A. macrophyllum). The symptoms begin in the spring as small greenish-yellow spots on the upper leaf surface that, by mid-summer, progress to black tar-like spots about 0.5 inch in size. The disease is not fatal to the tree, but the appearance of the tar spots alarms some tree owners. A major outbreak in New York about 10 years ago left many maples completely defoliated by mid-August.

Resources:

Diplodia Tip Blight of Two-Needle Pines, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Boxwood Blight, The Education Store

Disease of Landscape Plants: Cedar Apple and Related Rusts on Landscape Plants, The Education Store

Planting Your Tree Part 1: Choosing Your Tree, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Tree Planting Part 2: Planting a Tree, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Purdue Landscape Report

Janna Beckerman, Professor of Plant Pathology

Purdue Department of Botany and Plant Pathology

As trees grow and reach heights which many consider to be unsafe, tree owners would often top their trees by reducing the tree size. This is by heading back most of the large, live branches from the tree. However, topping trees proves to be more damaging than beneficial.

As trees grow and reach heights which many consider to be unsafe, tree owners would often top their trees by reducing the tree size. This is by heading back most of the large, live branches from the tree. However, topping trees proves to be more damaging than beneficial.

Topping trees can cause decay, weak branch attachments, and an increased likelihood of failure. If we do not top our trees and leave them to develop naturally, the structural strength of the trees is stronger than those that are not topped. The extensive root system, when left undisturbed, provides adequate support for the trees.

This publication titled What’s Wrong with Topping goes in-depth on the implications of topping and provides better alternatives to topping.

To view other urban forestry publications and video resources, check out Purdue Extension’s The Education Store website.

Resources:

Planting Your Tree Part 1: Choosing Your Tree, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Tree Planting Part 2: Planting a Tree, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Tree Selection for the “Un-natural” Environment, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

Tree Pruning Essentials Video, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Lindsey Purcell, Urban Forestry Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Spring is here! It is the time of year for some of us to be planting new trees. In this Ask an Expert session, we welcome Lindsey Purcell, urban forestry specialist, as he teaches us how to plant and properly care for our trees. He goes over the tree selection process, including which invasive species trees we should avoid, and how to continue to take care of our trees once planted.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning, or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Resources:

Planting Your Tree Part 1: Choosing Your Tree, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Tree Planting Part 2: Planting a Tree, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Indiana Invasive Plant List, Indiana Invasive Species Council, Purdue Entomology

Alternatives to Burning Bush for Fall Color, Purdue Landscape Report

Invasive Plant Species: Callery Pear, Youtube, Purdue Extension

Equipment Damage to Trees, Purdue FNR Extension

Landscape Report Shares Importance of Soil Testing, Purdue FNR Extension

Lindsey Purcell, Urban Forestry Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Question: Can I plant grass over soil where a newly removed stump was ground out?

Answer: We generally don’t want to plant new trees or turf immediately over the top of existing stumps in landscapes. The reasoning is a bit complicated but somewhat simple. The stump  location will have limited soil and rooting depth for nutrient uptake and structural stability due to its remaining below ground mass.

location will have limited soil and rooting depth for nutrient uptake and structural stability due to its remaining below ground mass.

The woody debris material created from stump grinding has a high carbon to nitrogen (C:N) ratio. This reduces nitrogen availability for the new tree or grass. Also, there will be significant settling of the ground below the stump as it decays and loses its structural fiber. The soil should be added to replace the below ground roots and stump. It can take several years to fully decompose the stump unless it was ground very deeply or removed with an excavation machine.

The recommendations are adding soil to the stump area, and a little additional soil mounded to compensate for some decay. Plant the grass, preferably sod, however, seed can work, to adequately cover the newly exposed area. Be sure to add slow-release turf fertilizer to compensate for the high C:N ratio that will be robbing nutrition from the newly installed turf. Maintain adequate moisture and look for signs of yellowing, indicating low nitrogen levels.

Also, sprouts may be generated due to the roots acting as energy storage for the tree. Simply treat them with typical lawn herbicide as needed at the label recommended rates.

Resources:

Taking Care of Your Yard: Homeowner’s Essential Guide to Lawns, Trees, Shrubs, and Garden Flowers, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Homeowner Conservation Practices to Protect Water Quality, Purdue Rainscaping, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Planting Your Tree Part 1: Choosing Your Tree, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Purdue Landscape Report

Lindsey Purcell, Chapter Executive Director

Indiana Arborist Association

Curious about the upcoming cicada emergence? What is different about this species than the ones you see every summer? What effect can they have on wildlife or on your trees and shrubs? Find out from Purdue Extension wildlife specialist Jarred Brooke, forester Lenny Farlee and Purdue Entomology’s Elizabeth Barnes. Don’t miss the question and answer time with our experts discussing “all things cicadas”.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Resources:

Billions of Cicadas Are Coming This Spring; What Does That Mean for Wildlife?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR)

17-year Cicadas Are Coming: Are You Ready?, Purdue Landscape Report

17 Ways to Make the Most of the 17-year Cicada Emergence, Purdue College of Agriculture

Periodical Cicada in Indiana, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Cicada Killers, The Education Store

Purdue Cicada Tracker, Purdue Extension-Master Gardener Program

Dr. Elizabeth Barnes, Exotic Forest Pest Educator

Purdue Department of Entomology

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

Jarred Brooke, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

Recent Posts

- Leaving Leaves Benefits Wildlife – Wild Bulletin

Posted: November 11, 2024 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - Purdue Extension’s Showcase, Impacting Indiana

Posted: November 8, 2024 in Community Development, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, Land Use, Natural Resource Planning, Timber Marketing, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Wood Products/Manufacturing, Woodlands - When Roundup Isn’t Roundup – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: October 17, 2024 in Forestry, Gardening, Plants, Urban Forestry - Celebrate Pollinator Week With Flowers of June Tour

Posted: June 20, 2024 in Forestry, Gardening, Wildlife - Ask An Expert: What’s Buzzing or Not Buzzing About Pollinators, Webinar

Posted: July 4, 2023 in Forestry, Gardening, How To, Plants, Wildlife - Magnificent Trees of Indiana Webinar

Posted: May 12, 2023 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, Got Nature for Kids, Urban Forestry, Webinar, Woodlands - Be Tick Aware: Lyme Disease & Prevention Strategies Webinar

Posted: May 11, 2023 in Alert, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, How To, Urban Forestry, Webinar, Wildlife, Woodlands - Illinois Groundwork provides a rich supply of green infrastructure resources – IISG

Posted: in Gardening, Land Use, Plants, Wildlife - Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae on lilac and other woody ornamentals – Landscape Report

Posted: May 3, 2023 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, How To, Plants, Safety, Urban Forestry, Woodlands - Publication-Introduction to Rain Garden Design

Posted: April 24, 2023 in Forestry, Gardening, How To, Plants

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands