Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

Cockroaches are serious threats to human health. They carry dozens of types of bacteria, such as E. coli and salmonella, that can sicken people. And the saliva, feces and body parts they leave behind may not only trigger allergies and asthma but could cause the condition in some children.

A German cockroach feeds on an insecticide in the laboratory portion of a Purdue University study that determined the insects are gaining cross-resistance to multiple insecticides at one time. (Photo by John Obermeyer/Purdue Entomology)

A Purdue University study led by Michael Scharf, professor and O.W. Rollins/Orkin Chair in the Department of Entomology, now finds evidence that German cockroaches (Blattella germanica L.) are becoming more difficult to eliminate as they develop cross-resistance to exterminators’ best insecticides. The problem is especially prevalent in urban areas and in low-income or federally subsidized housing where resources to effectively combat the pests aren’t as available.

“This is a previously unrealized challenge in cockroaches,” said Scharf, whose findings were published in the journal Scientific Reports. “Cockroaches developing resistance to multiple classes of insecticides at once will make controlling these pests almost impossible with chemicals alone.”

Each class of insecticide works in a different way to kill cockroaches. Exterminators will often use insecticides that are a mixture of multiple classes or change classes from treatment to treatment. The hope is that even if a small percentage of cockroaches is resistant to one class, insecticides from other classes will eliminate them.

Scharf and his study co-authors set out to test those methods at multi-unit buildings in Indiana and Illinois over six months. In one treatment, three insecticides from different classes were rotated into use each month for three months and then repeated. In the second, they used a mixture of two insecticides from different classes for six months. In the third, they chose an insecticide to which cockroaches had low-level starting resistance and used it the entire time.

In each location, cockroaches were captured before the study and lab-tested to determine the most effective insecticides for each treatment, setting up the scientists for the best possible outcomes.

“If you have the ability to test the roaches first and pick an insecticide that has low resistance, that ups the odds,” Scharf said. “But even then, we had trouble controlling populations.”

For full article: Rapid cross-resistance bringing cockroaches closer to invincibility.

Resources

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Agriculture & Indiana Invasive Species Council

Purdue experts encourage ‘citizen scientists’ to report invasive species, Purdue Agriculture News

New Hope for Fighting Ash Borer, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

Mile-a-Minute Invasive Vine Found Indiana, Got Nature? Blog

Sericea Lespedeza: Plague on the Prairie, Got Nature? Blog

Michael E. Scharf, Professor and O.W. Rollins/Orkin Chair

Purdue Department of Entomology

Brian J. Wallheimer, Science Writer

Purdue College of Agriculture

A “weedy” field like this may seem unsightly to some, but to wildlife, it provides invaluable food and cover. Just by leaving this field unmowed, you can improve habitat on your farm.

Mowing just to clean up the farm, or Recreational Mowing Syndrome (RMS), eliminates habitat for countless wildlife species.

Do you have a sudden urge to jump in the tractor and mow your fields, field borders or road ditches?

You might have RMS.

Do you enjoy spending your weekend in the cab of the tractor with a mower in tow in search of places to mow across your property?

You might have RMS.

Do you get queasy at the sight of a “weedy” unkempt field?

You might have RMS.

What is RMS you ask? RMS stands for Recreational Mowing Syndrome, a condition that afflicts many rural landowners during the summer months. And if you answered yes to any or all of the questions above, then you have RMS.

What is it?

RMS is the sudden urge many landowners get to ‘clean’ up their property by mowing the ideal fields, field borders, and road ditches around the farm during the summer months. While a mowed field may look attractive in the eyes of a landowner, in the eyes of wildlife, this is a serious problem.

These prime mowing spots provide habitat for a suite of birds, mammals, herpetofuana, and pollinating insects that inhabit our rural landscapes. Many of these species are actively nesting or raising young in these areas during peak mowing season – April through September. And the weeds coming up in these fields like common milkweed, tall ironweed, common ragweed, and many others provide food and cover for wildlife.

How to treat it?

The easiest way to treat RMS is by going cold-turkey – park the tractor for the summer. If you are not ready to give up mowing all together, then restrict your mowing to just the lanes around the fields, instead of the whole field. If you are ready to give up mowing, but still want to enjoy time in the tractor, try these options.

Instead of hooking up the mower, hook up the sprayer and go control some invasive species on the property, like bush honeysuckle, autumn olive, or sericea lespedeza. Or try hooking up the disk and disking around the field to prepare firebreaks for a late summer or fall prescribed fire.

You can still spend time on the tractor during the summer months without eliminating wildlife habitat through mowing. In fact, you can improve it!

Next time you look at your window and see a “weedy” field, don’t cringe and give into the urge to mow it. Instead, just smile and listen to all the quail whistling, songbirds singing, and bees buzzing in the habitat you improved by not mowing.

Resources

Renovating native warm-season grass stands for wildlife: A Land Manager’s Guide, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Effective Firebreaks for Safe Use of Prescribed Fire, Got Nature?, Purdue Extension – FNR

Sericea Lespedeza: Plague on the Prairie, Got Nature?, Purdue Extension – FNR

Jarred Brooke, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

Question: I have noticed that a lot of very mature (> 80 ft) sycamore trees look ill. They don’t seem to have as many  leaves, or as large as they usually get and some have already turned brown and died. There are at least 2 in my 5 acres of woods and have noticed the same with other sycamores while driving from Mooresville to Indianapolis. Is there a certain blight/canker/pest that is damaging sycamores this year?

leaves, or as large as they usually get and some have already turned brown and died. There are at least 2 in my 5 acres of woods and have noticed the same with other sycamores while driving from Mooresville to Indianapolis. Is there a certain blight/canker/pest that is damaging sycamores this year?

Answer: I have also noticed that many sycamores appear relatively bare and may have brown or wilted leaves on the stems and littering the ground around the trees. The culprit is sycamore anthracnose, a fungal disease that causes damage and death of leaves as well as stem cankers. Sycamore anthracnose symptoms can be severe when we have cool, moist spring weather at the time of bud-break and leaf emergence , but healthy trees generally recover and put on new leaf area once the environmental conditions that favor the disease change to the warmer, drier conditions of late spring and summer.

Normally, the best management practices for sycamore anthracnose are patience and maintaining good tree health. The disease cycle is dependent on cool, moist spring weather, so it will run its course by late spring or summer when the average temperatures rise. Trees that are repeatedly defoliated could be reduced in vigor and be more susceptible to other problems, so steps to promote good tree health can be used as a preventative measure.

Resources:

Fertilizing Woody Plants – The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Diseases of Landscape Plants (leaf diseases) – The Education Store

Sycamore – The Education Store

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series – The Education Store

Anthracnose of Shade Trees – Purdue Plant and Pest Diagnostic Laboratory

Purdue Plant Doctor App- Purdue Extension

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Kristol from Tippecanoe County, IN, sent in question to the Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources experts (Ask an Expert ) asking what resources are available to help with landscaping for a front yard and sidewalk area that accumulates water after a hard rain. She also asked for resources to improve drainage.

) asking what resources are available to help with landscaping for a front yard and sidewalk area that accumulates water after a hard rain. She also asked for resources to improve drainage.

Purdue Extension has several articles and resources to help with this type of situation.

The resources in our Rainscaping and Master Gardeners Program shares several neat options:

Rain Gardens Go with the Flow, Indiana Yard and Garden, Purdue Horticulture

Rainscaping Program

Master Gardeners Program

Don’t miss the publications located in the Purdue Extension resource center, The Education Store, relating to the topic:

Tree Installation: Process and Practices

Planting Forest Trees and Shrubs in Indiana

Climate Change: How will you manage stormwater runoff?

For Midwest Landscapes, have a look at the Purdue Landscape Report:

Purdue Landscape Report

Check out upcoming workshops available for land and woodland owners, to talk with an expert:

Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources Calendar

Check out our Got Nature? posts as well, as this is always a great resource for new information:

Got Nature?, Forestry and Natural Resources-Purdue Extension

These resources give you lots of options that match what your looking for along with experts in the field to contact if needed.

We always appreciate the questions coming in, so keep them coming. Our experts will respond quickly and give you the guidance you need for your next steps.

Diana Evans, Extension Information Coordinator

Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

If you’ve ever had to work on a tree leaf collection, no doubt you included a leaf from Indiana’s state tree. Also known as tulip poplar and yellow poplar, the tuliptree is actually not a poplar at all. It is a member of the magnolia family known botanically as Liriodendron tulipifera.

The tuliptree is native to most of the eastern half of the United States and prefers rich, moist, well-drained, loamy soil. It is found throughout Indiana, but it is more prevalent in the southern two-thirds

of the state.

Its unusual flowers inspired the common name. The flowers are shaped much like a tulip with greenish-yellow petals blushed with orange on the inside. Because they generally are found high in the leaf canopy, the flowers often go unnoticed until they drop off after pollination. The leaves of this tree are also quite distinct — each one has a large, V-shaped notch at the tip.

Because tuliptrees transplant easily and grow fast, they are a popular choice for in home yards. But don’t be fooled by its small size in the nursery. Give a tuliptree plenty of room in your landscape plan. A tuliptree can reach as tall as 190 feet where it’s allowed to thrive, but it is more likely to reach 70 feet tall as a mature landscape specimen. Tuliptree is not without its share of pests and diseases. Among the most common are leaf spots, cankers, scale insects, and aphids….

For full article view “State tree a popular landscape choice,” Morning AgClips.

Related Resources:

Pruning Ornamental Trees and Shrubs, The Education Store-Purdue Extension resource center

Tulip Poplar: Is Indiana’s State Tree a Protector for the Rare American Ginseng Plant?, GotNature?, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Rosie Lerner, Extension Consumer Horticulturist

Purdue University, Horticulture & Landscape Architecture

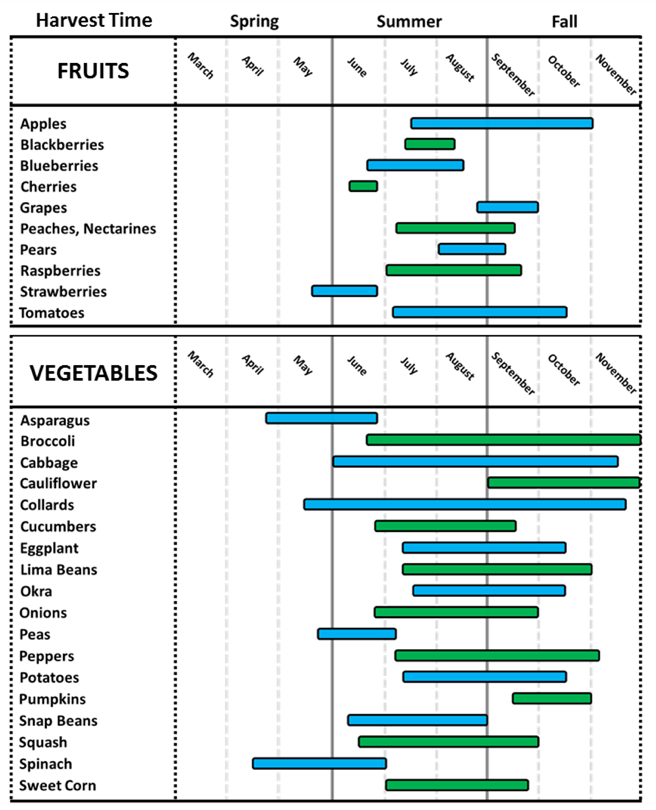

Choosing fruits and vegetables at the store is fast and easy but the task of fruit and vegetable selection can also be rewarding and a learning experience. There are a number of pick-your-own farms here in Indiana that allow you the freedom of choosing from a vast selection of produce freshly-picked from or still on the tree, vine, or bush. Several of these farms also boast gift shops where freshly-made pies and cakes can be purchased. Others offer a host of additional bonuses like tours, hayrides, and picnic areas. On those days when you want to commune with nature and “live” off of the land. Visit an IN farm and pick-your-own.

There are dozens of farms listed (http://www.pickyourown.org/IN.htm) on this site but more may exist. Do some internet searching to discover the location that best suits your needs and hopefully you will enjoy a number of meals fresh from the farm this year.

This harvest calendar will help inform you about produce likely to be available at a certain time.

Please note that dates for Spring, Summer, and Fall may be flexible as seasons are typically based on the astronomical calendar, where rigid dates are assigned to the seasons (i.e. March 20th, 2018 = Spring in Indiana) based on the position of the Earth in relation to the sun, as opposed to the meteorological calendar, where actual weather conditions dictate crop growth. The easiest way to be assured that the produce you want to pick will be in season is to call the farm before your visit and use the calendar below as a general guide.

References:

2018 Seasons Calendar

Pick-Your-Own Farms in Indiana

Indiana Harvest Calendar

Other resources:

Fruit and Vegetable Care (place keyword in the search field ), The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Purdue Landscape Report, Purdue University

Calendar with Upcoming Workshops, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources

Shaneka Lawson, USDA Forest Service/HTIRC Research Plant Physiologist/Adjunct Assistant Professor

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Seeding rates for native warm-season grass and forb mixtures (NWSG) have changed drastically over time. In the past, native grasses were planted without forbs at rates exceeding 10 lbs/ac. This may be ideal from a forage production standpoint, but this created dense stands of native grass with little to no forb component and lacked benefits to most wildlife.

Mixtures have shifted from heavy planting rates of tallgrass species with few forbs to reduced rates of mid-stature grasses with an abundance of forbs. Recommended seeding rates of some current mixtures may be lower than what no-till drills are capable of planting. In this case, fillers may be needed to increase the bulk weight of the seed to allow the equipment to plant at the correct rate.

Seed mixtures are also more commonly being established by broadcasting seed during late winter (frost seeding) using cyclone fertilizer spreaders. Broadcasting native warm-season grass and forb seed usually requires the use of a carrier to ensure the mixture flows correctly through the spreader and the seed is distributed evenly across the field.

Using fillers when no-till drilling native warm-season grass and forb mixtures

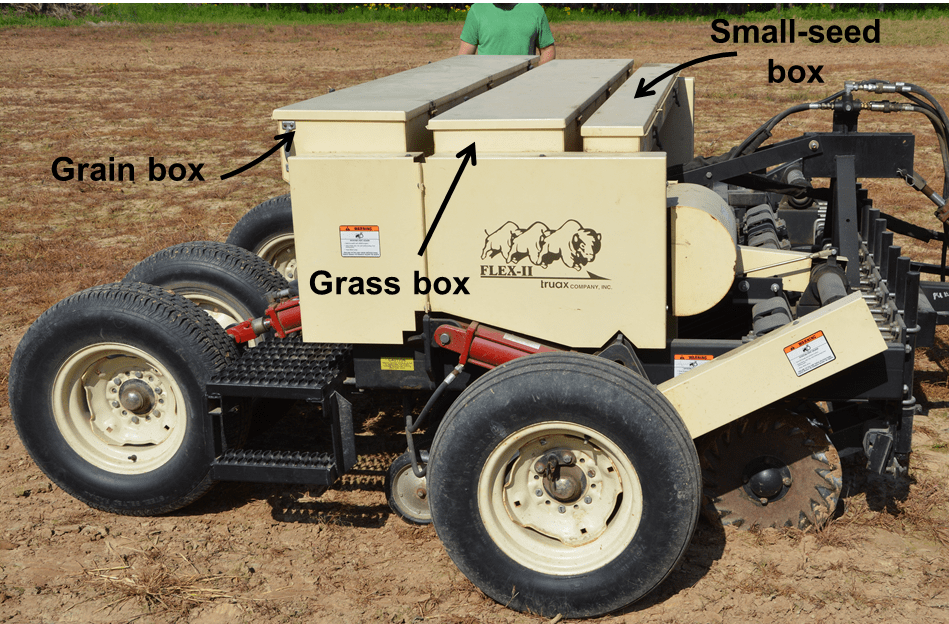

Planting native grass and forb mixtures with a no-till drill is the most common establishment method for NWSG plantings. It may be difficult to achieve the correct seeding rate with a no-till drill because of the combination of reduced bulk weight of dechaffed seed and reduced seeding rates of common mixtures. Fillers can be used to increase the bulk weight of native grass and forb seed if a drill cannot achieve the recommended seeding rate. Traditionally, native grass and forbs have been planted separately using the grass or fluffy-seed box for the native grass seed and the small-seed box for the forbs. However, if the seed has been cleaned and dechaffed it is common for seed companies to mix the seed and recommend it be planted together using the fluffy or grain box on a no-till drill. Fillers can be used when planting native grasses and forbs separately or when planting native grass and forb mixtures. Refer to the chart below for recommended fillers for the different seed boxes of a no-till drill.

Example:

We are planting a 10-acre field to a native warm-season grass and forb mixture using a no-till drill. The recommended seeding rate is 6 lbs/acre. The seed will be planted with the grain box of the drill, but the drill will only plant a minimum of 10 lbs/acre of our seed mixture.

10 acre field * 6 lbs/acre bulk seeding rate = 60 lbs of the seed mixture

Minimum seeding rate for the no-till drill is 10 lbs/acre = 10 lbs/acre * 10 acres = 100 lbs

We need to add a filler to increase the bulk weight of the seed mixture to be able to plant at the correct seeding rate. We added a 1:1 ratio (by weight) of cracked corn to our seed mixture:

60 lbs of seed + 60 lbs of cracked corn = 120 lbs of bulk weight for 10 acres

We now need to adjust our bulk seeding rate to account for the added crack corn.

120 lbs of bulk weight for 10 acres = 12 lbs/acre

We need to calibrate our drill to plant 12 lbs/acre in order to plant 6 lbs/ac of our initial seed mixture.

Generally, you should use a 1:1 ratio (by weight) of filler-to-seed, but in some cases you may need to use a higher ratio (e.g., 2:1, 3:1, or 4:1 filler-to-ratio) to achieve the correct seeding rate.

Using carriers when broadcasting native warm-season grass and forb mixtures

Broadcasting native warm-season grass and forbs mixtures is most commonly accomplished with a cyclone fertilizer spreader. These spreaders may have issues broadcasting the native grass and forb seed. The 2 main issues are: (1) the seed is not heavy enough to flow through the spreader and (2) the seeds of various size will settle and will not be spread evenly across the field. Carriers will add more bulk weight to the native grass seed and will help ensure the seed stays mixed across the field. Common carriers that are used with native grasses are cracked corn, pelletized lime, wheat, or oats. The recommended rates of common carriers are in the table below:

Pelletized lime

Wheat

Oats

Cracked corn

200 lbs/acre

40 lbs/acre

32 lbs/acre

1:1 ratio of seed-to-cracked corn by weight

Table adapted from the publication Warm season grass establishment,

Indiana Department of Natural Resources, 2006.

Example:

We plan to broadcast a native grass and forb mixture on a 10-acre field. The recommended bulk seeding rate is 6 lbs/acre.

10 acre field * 6 lbs/acre bulk seeding rate = 60 lbs of the seed mixture

We need to add a carrier to the mixture to increase the bulk weight of the seed mixture. We plan to add 200 lbs of pelletized lime per acre:

200 lbs/ac of lime * 10 acres = 2000 lbs of lime

60 lbs of seed + 2000 lbs of pelletized lime = 2060 lbs of bulk weight for 10 acres

We now need to adjust our bulk seeding rate to account for the added pelletized lime.

2060 lbs of bulk weight for 10 acres = 206 lbs/acre

We need to calibrate the spreader to broadcast 206 lbs/acre in order to plant 6 lbs/acre of our seed mixture.

Conclusions

Planting native warm-season grass and forb mixtures at the correct rate is a critical step in ensuring a successful planting. Using fillers and carriers when establishing native warm-season grasses and forbs can help ensure the mixtures are planted at the proper rates, flow correctly through the seeding equipment, and ensure the seed is spread evenly across the field.

Other Resources:

Pure Live Seed: Calculations and Considerations for Wildlife Food Plots, Detailed Resource, Purdue Extension-FNR

Renovating Native Warm-Season Grass Stands for Wildlife: A Land Manager’s Guide, free pdf download

Calibrating a No-Till: FNR 556-WV, free pdf download

VIDEO: Calibrating a No-Till Drill for Conservation Plantings and Wildlife Food Plots

VIDEO: Frost Seeding to Establish Wildlife Food Plots & Native Grass and Forb Plantings

Printable Version:

PDF available for print: Seed Fillers and Carriers for Planting Native Warm-Season Grasses and Forbs (pdf 771.45) detail resource.

Moriah Boggess, Purdue Extension Wildlife Intern

Jarred Brooke, Purdue Extension Wildlife Specialist

Have you heard the old adage “proper planning prevents poor performance?” This adage applies perfectly to establishing food plots for wildlife; you just have to adjust the words, “Proper planting prevents poor food plot performance”.

When we talk about planting we include planting method, timing, depth, and planter calibration (see video), but we also include seeding rate. While there are many steps prior to planting to ensure a successful food plot, including taking a soil test, adjusting the soil fertility, and proper site preparation, determining the proper seeding rate based on pure live seed rather than bulk weight may be one aspect that people skip or ignore.

All agronomic seeds have a recommended seeding rate. This is the rate that maximizes forage or grain production and minimizes seed costs. Planting food plot seed too heavily is often a waste of money, because it increases your seed cost, but does not necessarily increase you forage or grain production. Planting food plots too lightly is an inefficient use of field space, opening areas up for weeds to overtake your planting, and could result in failure because of overbrowsing.

Seeding rate also varies by planting method and it’s important to make sure to follow the recommended seeding rate for the planting method you will be using. This rate is greater when broadcasting rather than when drilling or planting seed (broadcast rate: 75-100 lbs/ac vs. drilling rate: 50 lbs/ac for iron-clay cowpeas).

It is important to recognize the difference in how seed is sold (bulk weight) and how seeding rates are recommended (pure live seed [PLS]). When you buy seed from a supplier you are buying it in the form of bulk weight. Bulk weight is the total weight inside the bag, including the food plot seed, as well as the weight of the seed coating and other material (other crop seed and weed seed).

While seed is sold by bulk weight, seeding recommendations are commonly given as PLS rates. This distinction is important. For example, all the recommendations in A Guide to Wildlife Food Plots and Early Successional Plants by Dr. Craig Harper, University of Tennessee Extension are given in PLS rates. Pure live seed is the living seed of the intended crop that will germinate from a seed bag and accounts for the weight of the bag made up of impurities, weed seed, and other crop seed.

Percent PLS in a seed bag varies, depending on the amount of pure seed in the bag as well as the germination rate of that seed. It is important to know the difference between PLS and bulk weight so that you can calculate the amount of bulk weight you need to achieve the recommended PLS seeding rate.

Keep the distinction between bulk weight and PLS weight in mind when buying seed to ensure you purchase enough seed to cover the entire area of your food plot. In this article we will explain how to calculate PLS based on information given to you when you purchase seed.

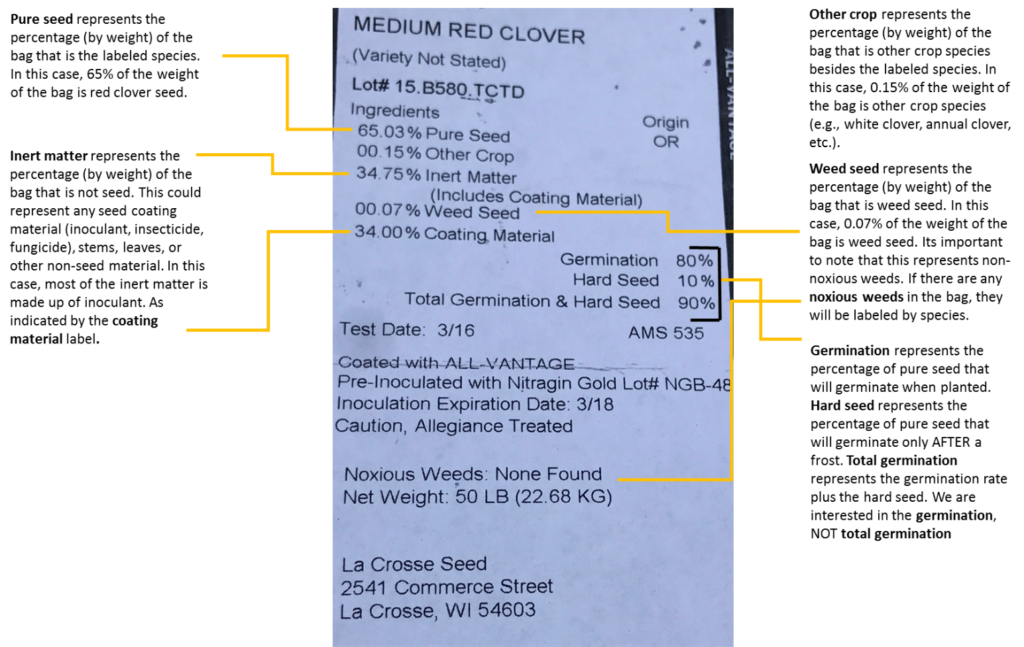

Dissecting a seed tag – know what you’re getting before you purchase

Before we get too far into calculating PLS, it is important to understand what information you get when purchasing seed. Regardless of whether you buy a seed mix or a single species from a co-op, feed store, or sporting goods store, all agricultural seed sold in Indiana must come with a label – commonly called a seed tag. By law, that seed tag must contain these 12 items: 1) commonly accepted name (species) and variety, 2) lot number, 3) origin of seed, 4) company who labeled the seed, 5) percentage of pure seed (>5% of weight), 6) percentage of other crop seeds, 7) percentage of inert matter, 8) percentage of weed seed, 9) species and amount of any noxious weeds (if present), 10) germination rate, 11) hard seed, and 12) calendar month and year the bag was tested.

Important items to look for when purchasing seed are explained below.

As we can see from this red clover seed tag above, only 65% (32.5 lbs) of the 50 lb bag is actually red clover (Pure Seed). Most of the other weight is the inoculant (Coating Material; 34% or 17 lbs). Of the 32.5 lbs of red clover seed, 80% will germinate after planting (Germination). So, if you planted 15 lbs (bulk weight) from this bag (recommended PLS rate) you would actually be planting 9.75 lbs of pure seed, of which only 7.8 lbs would germinate. Meaning you would be planting a little over half the recommended rate. See why PLS is so important now?

Clover seed: bag half empty or half full?

It may seem odd to buy a 10 lb clover seed bag only to expect 5 lbs to actually grow, but in the case of legumes – like clovers – the 5 lbs in the bag that isn’t seed may actually save you money in the long run. Having as little as 50% PLS in a bag of clover is not uncommon, as much of the weight is made up of the seed coating, which is typically an inoculant. The inoculant on clover, soybeans, alfalfa, or other legumes is living bacteria that help fix nitrogen from the air and make it usable to plants. Planting inoculated seed – whether you inoculate it yourself or purchase pre-inoculated seed – reduces the amount of nitrogen fertilizer needed, ultimately saving you money on fertilizer application. The benefit of buying pre-inoculated seed is that it saves you the hassle of inoculating the seed yourself.

Calculating pure live seed (PLS)

Now that you know the importance of reading the seed tag before purchasing seed, you can now think about calculating PLS. All the information you need is right there on the tag. Using the example seed tag below locate the two items labeled “PURE SEED” and “GERMINATION”.

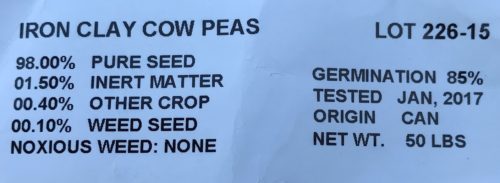

Our example is 98% pure seed, meaning in a 10 lb bag there are 9.8 pounds of pure iron-clay cowpea seed. The next number we will need is the germination rate; this will also be indicated as a percentage. Our example has an 85% germination rate.

To calculate percent PLS for this seed, multiply pure seed and germination and then multiply by 100 (example below). The result is the percentage of pure live seed for this bag of seed.

98% pure seed

85% germination

(0.98 x 0.85) x 100 = 83% (Percent PLS)

We now know that 83% of our bag is iron-clay cowpeas capable of germinating. Now that we have the PLS of our seed we can calculate the amount (lbs) of pure live seed in our bag. To do this, multiply the bulk seed weight by the percent PLS.

50 lb bag x 0.83 (Percent PLS) = 42 lbs PLS

For example, a 50 lb bag would equal 42 lbs of iron-clay cowpea seed that will germinate.

Determining bulk seed rate

Using the percent PLS information we can also find the amount of bulk seed necessary to plant at a recommended seeding rate. To do this, take the recommended seeding rate for your planting method and divide it by the percent PLS of the seed you are using (example below). The result is the bulk weight that you will need to plant per acre to achieve the recommended seeding rate.

50 lbs/acre = recommended seeding rate for iron-clay cowpeas when drilling

0.83 = percent PLS of seed being planted (from example above)

50/0.83 = 60 lbs/acre

In order to plant a cowpea food plot at the recommended rate of 50 lbs/acre, we will need to plant 60 lbs/acre from this particular seed bag.

Another benefit of calculating pure live seed? Comparing seed prices

Not all seeds are of the same quality. Some have lower pure seed and germination rates than others. For this reason, it is not always most cost effective to buy the cheapest bag of seed on the shelf. If you wish to compare pure live seed prices between seed bags, first divide the price of the bag by the weight of the bag. This will give you the price per pound of bulk seed (example below). Now divide this price per pound by the percent PLS of the seed. The result is the price per pound of PLS.

Seed Manufacturer X 10lbs

Pure seed 97%

Germination 92%

Price $33

PLS (0.97 x 0.92) x 100 = 89%

$/lb (bulk) 33/10 = $3.30/lb

$/lb (PLS) 3.3/0.89 = $3.70/lb

Seed Manufacturer Y 10lbs

Pure seed 91%

Germination 82%

Price $30

PLS (0.91 x 0.82) x 100 = 74.%

$/lb (bulk) 30/10 = $3/lb

$/lb (PLS) 3.0/0.74 = $4.05/lb

According to these calculations, seed manufacturer X is actually a better value than Y. Using this process, especially when purchasing seed in bulk, you can be a practical money saver.

Let’s Plant

Now that you know what all those numbers on the seed tag of your favorite food plot seed mean and you know how to calculate PLS, you will be able to plant your food plots at the most effective rate possible. Remember, regardless of whether you are planting acres of soybeans with a no-till drill or frost seeding a ½-acre clover patch, knowing how to calculate PLS will allow you to be more successful and save money when planting food plots.

Other Resources:

Seed Fillers and Carriers for Planting Native Warm-Season Grasses and Forbs, Detailed Resource, Purdue Extension-FNR

Renovating Native Warm-Season Grass Stands for Wildlife: A Land Manager’s Guide, free pdf download

VIDEO: Calibrating a No-Till Drill for Conservation Plantings and Wildlife Food Plots

VIDEO: Frost Seeding to Establish Wildlife Food Plots & Native Grass and Forb Plantings

Printable Version:

PDF available for print: Pure Live Seed: Calculations and Considerations for Wildlife Food Plots (pdf 636.75) detail resource.

Moriah Boggess, Purdue Extension Wildlife Intern

Jarred Brooke, Purdue Extension Wildlife Specialist

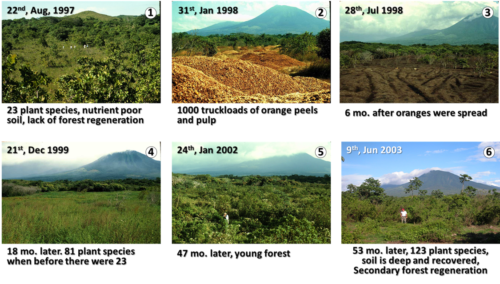

A recent study in Costa Rica by scientists at Princeton University-Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and the University of Pennsylvania-Ecology & Biodiversity showed how agricultural waste could help successfully remediate barren tropical forest sites.

A deal between an orange juice manufacturer and advisors for the Área de Conservación Guanacaste was struck that allowed 1,000 truckloads (12 metric tons) of orange peels and pulp to be unloaded on nutrient-poor soils dominated by invasive grass within one of Costa Rica’s national parks in the mid-1990s. The land was left to rest for sixteen years. Now, the forest has begun the lengthy process of regeneration and some secondary forest regeneration has been observed. The peels were spread over 3 ha (7 acres) and scientists measured an increase of 176% in aboveground biomass. The distinction between the orange-fertilized land and the unfertilized areas was pronounced. Orange-fertilized areas demonstrated more tree biomass and species diversity and richer soils than their counterparts.

To enlarge photo click on image. Photo credits: Tim Treuer, Daniel Janzen, Winnie Hallwachs, & Leland Werden.

This research shows what could happen when the environmental community and industry find a medium where they can work together to come up with problem solutions. Perhaps, in future, similar uses can be found for agricultural excess here in the United States.

References:

Treuer TLH, Choi JJ, Janzen DH, Hallwachs W, Peréz-Aviles D, Dobson AP, Powers JS, Shanks LC, Werden LK, Wilcove DS. (2017) Low-cost agricultural waste accelerates tropical forest regeneration. Restoration Ecology, DOI: 10.1111/rec.12565

Resources:

Indiana Forestry & Woodland Owners Association

Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources workshops

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Shaneka Lawson, USDA Forest Service/HTIRC Research Plant Physiologist/Adjunct Assistant Professor

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Wild animals have a dispersal period where young move on to new ground to establish their own home range. This is nature’s way of mixing the gene pool. It also allows for species to reoccupy small, isolated habitat patches. Late summer and early fall is a common time to see juvenile snakes because of dispersal.

Snake identification questions are one of my most common that I receive from the public. Usually, people want to know if the snake is venomous or not. Most snakes in Indiana are not venomous. In fact, there are only four venomous species in Indiana. Their distributions are generally limited.

The snake pictured here to the right is a Northern Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon). Photo and identification request was submitted to our “Ask an Expert” web submission by Mr. R. Dearing. While only about a foot long here, adults can reach several feet in length. Coloration in them is variable, but they typically have dark bands on a lighter tan or brown background. The bands are complete towards the head and fragment towards the tail. This little snake found its way into Mr. Dearing’s house. Fortunately, he was able to catch it and return it to the creek behind their house—which explains why it was there in the first place.

Resources:

Snakes and Lizards of Indiana, The Education Store, Purdue Extension

How can I tell if a snake is venomous, FAQs, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources

Indiana Amphibian and Reptile ID Package, The Education Store, Purdue Extension

Ask An Expert, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources

Brian MacGowan, Extension Wildlife Specialist

Department of Forestry & Natural Resources, Purdue University

Recent Posts

- Leaving Leaves Benefits Wildlife – Wild Bulletin

Posted: November 11, 2024 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - Purdue Extension’s Showcase, Impacting Indiana

Posted: November 8, 2024 in Community Development, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, Land Use, Natural Resource Planning, Timber Marketing, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Wood Products/Manufacturing, Woodlands - When Roundup Isn’t Roundup – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: October 17, 2024 in Forestry, Gardening, Plants, Urban Forestry - Celebrate Pollinator Week With Flowers of June Tour

Posted: June 20, 2024 in Forestry, Gardening, Wildlife - Ask An Expert: What’s Buzzing or Not Buzzing About Pollinators, Webinar

Posted: July 4, 2023 in Forestry, Gardening, How To, Plants, Wildlife - Magnificent Trees of Indiana Webinar

Posted: May 12, 2023 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, Got Nature for Kids, Urban Forestry, Webinar, Woodlands - Be Tick Aware: Lyme Disease & Prevention Strategies Webinar

Posted: May 11, 2023 in Alert, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, How To, Urban Forestry, Webinar, Wildlife, Woodlands - Illinois Groundwork provides a rich supply of green infrastructure resources – IISG

Posted: in Gardening, Land Use, Plants, Wildlife - Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae on lilac and other woody ornamentals – Landscape Report

Posted: May 3, 2023 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, How To, Plants, Safety, Urban Forestry, Woodlands - Publication-Introduction to Rain Garden Design

Posted: April 24, 2023 in Forestry, Gardening, How To, Plants

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands