Purdue Aphasia Research Lab explores understanding, treatment of debilitating disease

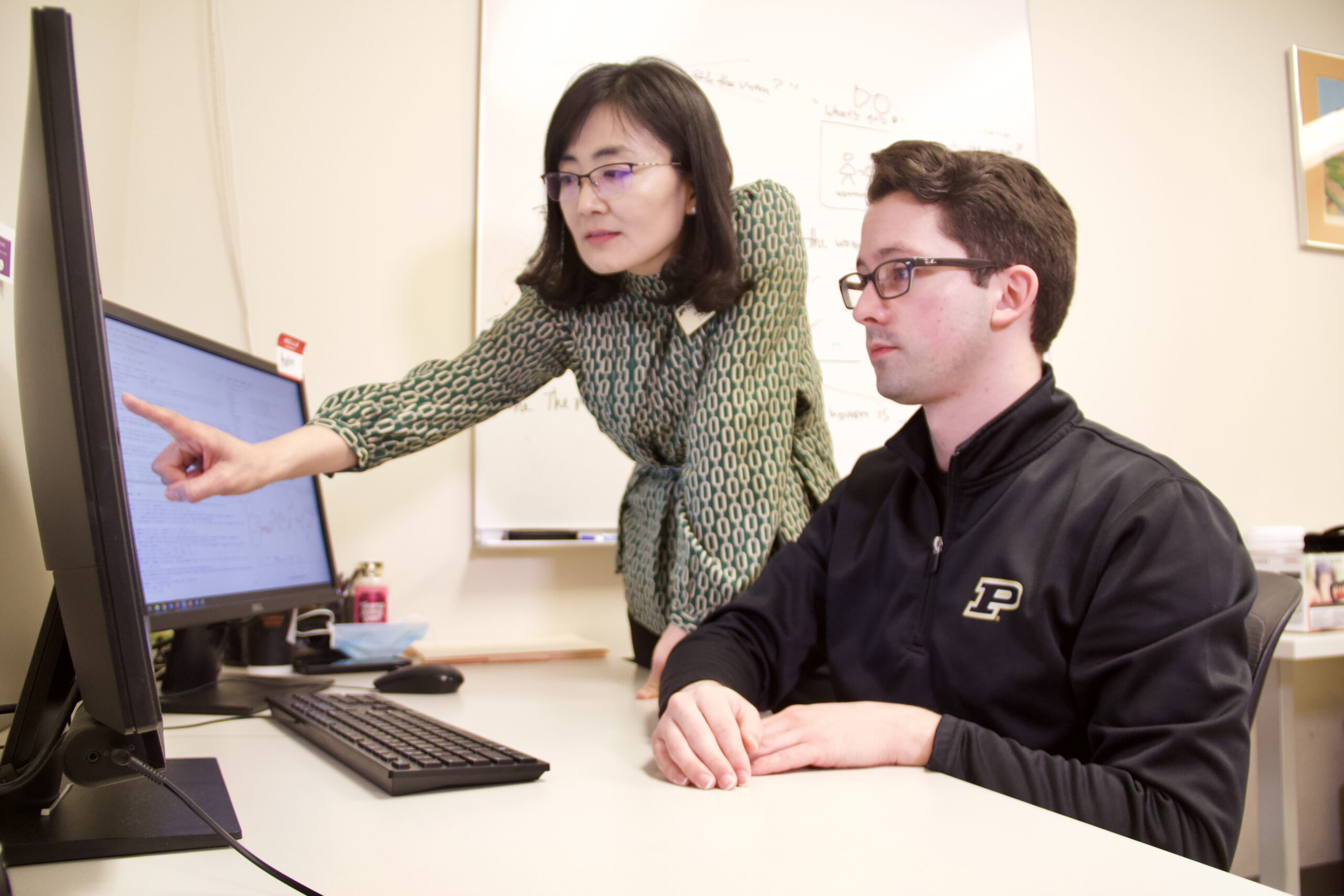

Jiyeon Lee, associate professor in the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, and her master’s student Austin Keen look at data collected from a recent experiment inside the Purdue Aphasia Research Lab.Tim Brouk

Written by: Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

Movie fans were shocked when actor Bruce Willis announced his retirement due to complications with aphasia.

The “Die Hard” actor stepped away after appearing in 144 films, according to IMDb. Many of Willis’ fans investigated what aphasia really is, giving mainstream exposure to the debilitating disease that affects a person’s ability to communicate verbally or through writing. It’s most acquired after a stroke or brain injury.

Jiyeon Lee, associate professor in the Purdue University Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, has studied individuals with aphasia for much of her career. Students in her aphasia class told her of the Willis news minutes after it broke.

“It’s really saddening that we can’t see Bruce Willis on the screen anymore,” Lee said. “However, I do appreciate his and his family’s courage to share his diagnosis of aphasia because it has increased the awareness of aphasia.”

Lee’s Aphasia Research Laboratory is a hub for learning more about the disease, exploring treatments and monitoring different phases of aphasia, thanks to community participants visiting the lab. Current projects center around patients who were stricken with aphasia after suffering strokes. Lee and her research team are developing a novel language training paradigm using implicit learning procedures to better produce and understand sentences.

“We work to better understand how people with aphasia understand and produce language and how we could facilitate the regaining of their language abilities,” Lee said. “The long-term goal of our lab is really to develop more cost-effective treatment approaches for these patients with aphasia and improve treatment options available to them.”

Tracking aphasia by eye

The fact that the person with aphasia can still think but can’t communicate as well — or at all — is one of the most difficult, and even terrifying, aspects of the condition. While speaking and writing is difficult for aphasia patients, Lee and her fellow researchers use technology to track the eye movements of participants to gauge how aware and responsive they are. After applying a small bullseye-like sticker above their left eye, a video camera calibrates onto the mark and the eye.

Lee’s students have developed video and audio exercises to gauge the participants’ eye and brain activity. As a laptop records the data, Lee and her research assistants can watch where the participant looks on a desktop computer screen. One exercise has audio of questions being asked, and the participant looks at the correct image. The questions are worded in ways to help the brain work — rhymes, similar cadence, clear wording. This method is called structural priming and is meant to help someone with aphasia produce sentences on their own.

“Although they may not be able to communicate as well as before, the person is still there,” Lee said.

The data is analyzed by Lee and her students in a separate room of her lab. Through spreadsheets and line graphs, they can see how participants are faring.

“Many patients with aphasia receive speech therapy,” Lee said. “Through speech therapy, aphasia actually gets better and improves significantly. There are also aphasia support groups that allow people to make connections with other people with aphasia and caregivers. It can be a great resource for them.”

Lee employs undergraduates, PhD candidates, master’s students and postdoctoral fellow Josh Weirick in her Aphasia Research Laboratory.

Audio of Weirick’s voice can be heard during some of the participants’ exercises and experiments. His young career is benefiting from Lee’s expertise as he works on multiple projects focusing on sentence comprehension by people with aphasia as they are reading in real time.

“It was a great opportunity to learn some new methods and a really great opportunity to learn how I can take the skills I learned doing my PhD in linguistics and apply them to help solve problems that will eventually lead to improved quality of lives of people with aphasia,” Weirick said.

Lee leads a meeting in the Purdue Aphasia Research Lab with Keen, left, and Weirick.Tim Brouk

During a recent visit to Lee’s lab, PhD candidate Grace Man was analyzing wave forms from patients’ speech data as they performed tasks. She then measured their accuracy; timing; and disfluencies, which are interruptions in the regular flow of speech. Another part of her work analyzes electroencephalogram, or EEG, data, which is in conjunction with Lee’s Aphasia Lab and Natalya Kaganovich’s Auditory Cognitive Neuroscience Lab.

Master’s student Austin Keen was plotting points from a recent eye-tracking study focusing on relearning language with the help of the screened images and audio of sentences and questions at his computer. The data breaks down where the eyes move word by word, syllable by syllable.

“It tells us a lot about where in a sentence they are able to comprehend or not able to comprehend. It gives us very good information about where in each step in the training or treatment process they are learning language,” Keen explained. “Being able to interact with our participants has been an amazing experience.”

Tragedy in spotlight

While Willis’ bout with aphasia is tragic for him and his fans, aphasia is being talked about more than ever.

“Many people around the world now know what aphasia is, and it’s really increasing the support we could possibly provide for people in the aphasia community,” Lee said.

While most patients may not fully recover, aphasia can be treated for a better quality of life, thanks to research conducted in the Purdue Aphasia Research Lab.

“Increasing the awareness of what aphasia is and teaching ourselves how to use aphasia-friendly communication, that would be really crucial for these patients,” Lee said.

Discover more from News | College of Health and Human Sciences

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.