Purdue Psychological Sciences researcher exploring fear memory ‘deflation’

Sydney Trask, assistant professor in the Department of Psychological Sciences, is currently studying fear memories at the cellular and molecular levels. She hypothesizes that fear “deflation” is a better approach to overcoming fear than “extinction” methodology. Tim Brouk

By Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

It’s been months since you were mugged in a dark parking lot. The anxiety and fear from the experience is still affecting your life. A therapist might suggest you revisit that same parking lot to face your fears.

This extinction method of diving right back into the fearful setting can have adverse effects on a patient, according to Sydney Trask, an assistant professor in the Purdue University Department of Psychological Sciences. Instead, Trask has developed a method she calls fear “deflation,” which chips away at the fearful stimulus in a more gradual manner. Trask’s work aims to introduce individuals to weaker versions of the thing that’s causing them fear to make it seem less intimidating.

“What happens with extinction is that it creates a brand-new memory,” Trask explained. “Rather than erasing the old memory, it creates a new memory that competes with the original.”

Through a nearly $2 million R01 grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, Trask will focus on the behavioral factors and neural processes that improve fear- and anxiety-related symptoms, contributing to her novel behavioral procedure of deflation. The grant money will be spread over a five-year period.

Most of the work will focus on the neurological processes at the cellular and molecular levels and long-lasting behavioral changes using rodent subjects.

The work is an extension of a study Trask published in 2023 through the Biological Psychiatry: Global Open Science journal where rats’ fear memories were tested through extinction and deflation methods.

Deflating disordered fear

Trask predicted deflation modifies the original fear memory, therefore affecting later responses to similar fearful situations. It could lead to better treatments for anxiety and fear-related conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Current treatments involve some extinction-based exposure therapies, which often result in relapse of fear responding, even when the symptoms seem to be completely gone. Deflation procedures would modify how patients react to the feared stimulus to reduce relapse.

The use of deflation could help patients suffering from phobias like the fear of spiders — arachnophobia. Quick flashes of images that a patient can’t remember seeing is a deflation-based therapy that reduces fear response in the brain.

Methodology

Trask will be studying two population models. All models will receive a fear stimulus. Then, the first population will be exposed to a traditional extinction method of fear removal involving presentations of the same fear stimulus, producing a reduction in the fear response. But this means the fear behavior is not erased. It comes back like Vecna from “Stranger Things.”

The second population will experience the same fear stimulus following conditioning, but this will be paired with lower-intensity exposures. In this deflation method, Trask presents a “very weak” version of the fear stimulus, enough for the rodent models to notice but not strike more fear. The goal is to manipulate the subjects’ thinking about the stimulus itself.

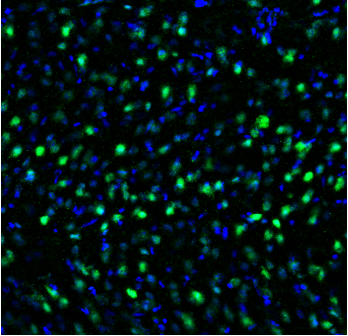

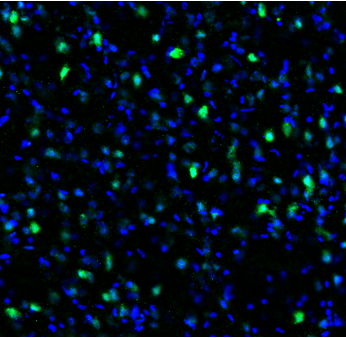

Trask will also measure how each procedure relies on certain brain regions, including the amygdala, a part of the brain that processes emotion. Within those regions, she will be detecting cellular overlap between neural cell activation and comparing this activity between deflation and extinction methods. She will be tagging neurons that are active during the original conditioning procedure. The next day, the models will be exposed to either deflation or extinction methods. The number of active tagged cells are then counted.

“We should be seeing more overlap in the deflation group than the extinction group. The extinction should create a whole new cellular pattern whereas the deflation should activate more of the original learning,” Trask said.

Deflation, in essence, retrains the brain by making it change the neurological response to the original fearful memory.

“We basically try to override that memory and say, ‘Hey, it’s just not as bad as you remember,’” Trask said.

Discover more from News | College of Health and Human Sciences

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.