Learning Objectives

- Describe the temperature conditions (i.e., ranges) under which cool-season and warm-season turfgrass species perform best.

- List common cool-season and warm-season turfgrass species and distinguish their growth habit.

- Describe what a cultivar is and why it is important to select improved cultivars when planting grass.

- Explain the optimum irrigation, mowing, seeding, fertilization, and traffic management practices to manage common cool-season turfgrass species in Indiana.

- List the three major nutrient requirements of turfgrasses

- Explain the purpose of turf soil testing

- Given a fertilizer label guaranteed analysis, determine the percentage of each of its nutrient components and calculate how much product is needed to treat a specified area when given the desired nitrogen rate

- Compare and contrast liquid fertilizer applications to granular fertilizer applications

- List advantages and disadvantages of slow-release fertilizers and quick-release fertilizers

- Describe the influence of site use (e.g., aesthetics, shade, age, etc.) on selection of a fertilizer program

- Describe in order the common steps in establishing turfgrass from seed or sod.

- Choose an appropriate seed mixture of blend for establishing different turf areas.

- Define what thatch is and how it can be managed in turf.

- List common abiotic and biotic turfgrass problems.

- Identify common turf weeds, insects, and diseases and their life cycle or when they commonly occur.

- Describe the benefits of a regular pest scouting program.

- Describe the relationship between turf cultural practices and pest pressure/environmental stress.

- Describe cultural pest control techniques to reduce pesticide use.

- Describe the different types of herbicides and common ways to improve their efficacy.

- Given a situation, choose the best control option for white grubs.

Introduction

The lawn is one of the most important and obvious parts of the landscape. It complements the ornamental plantings and it offers aesthetic, social, economic, and environmental benefits. Aesthetic benefits include the visual appeal of a nicely maintained lawn. Social benefits include opportunities for sports, recreation and relaxation. Economic benefits include increased values for homes/businesses with well-cared-for lawns and landscapes. Additionally, the numerous jobs created and dollars reinvested into the US economy from the turfgrass industry are economic benefits.

Turfgrass can also:

- Enhance air quality by trapping dust and reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide.

- Produce oxygen. One 5,000 square feet grass lawn can produce enough oxygen each day to support 14 to 34 people, depending on the location.

- Reduce stormwater runoff and soil erosion, which enhances groundwater recharge and improves water quality.

- Sequester soil carbon and nitrogen, which improves soil health.

- Cool its surroundings through evapotranspiration.

Proper establishment, fertilization, mowing, and irrigation are critical for both an attractive and functioning lawn. Maximizing the positive effects of these practices will enhance the benefits offered and minimize the need for pesticides, and will maximize the efficacy of pesticides if they are needed. This chapter focuses primarily on cultural practices that enhance turf health. Additional information about turfgrass management is available online at https://turf.purdue.edu/.

In this document, the terms turf or turfgrass are used to describe natural, living plants. There is no discussion of synthetic turf or AstroTurf which are sometimes called “turf” but are carpet materials made from plastic and crumb rubber infill. By definition, a turfgrass is a gramineous (grass), root-bearing plant that covers the land surface and tolerates traffic and defoliation. Turf can be defined as a collection of individual turfgrass plants that cover the soil surface. This is also termed a sward.

Cool-Season and Warm-Season Turfgrasses

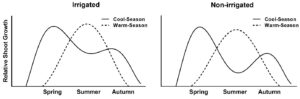

Grasses are commonly categorized as either cool or warm-season, although most lawn grasses in Indiana are cool-season. This categorization is based on how the plant makes and uses energy via photosynthesis. Cool-season species actively grow in the late spring and early fall and are less active in the summer when temperatures are too hot or in early spring and late fall when temperatures are too cool for optimum growth (Figure 1). Growth and net energy production of cool-season grasses is optimum from 68-77 °F. Cool-season species also typically keep some of their green color in the winter months, especially in southern Indiana. Warm-season species are actively growing in the summer months and will enter winter dormancy and lose their green color after the first hard frost (turn brown) through the remainder of the winter and do not green-up and resume growth until the following April or May. Warm-season grass growth and net energy production is optimum from 86-95 °F.

Choosing a Turfgrass Species

Although many species are capable of being maintained as an acceptable home lawn in Indiana, for brevity, this section has highlighted only the most commonly used species. These grasses can be classified in several ways:

Cool-season grasses vs. warm-season grasses

Cool-season grasses grow best when the weather is cool in spring and fall. Their growth slows during the hot, dry summer months. Common cool-season turfgrass species in Indiana include Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne), tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea), and fine fescues (Festuca spp.) (Table 1, Figure 2). Warm-season grasses [such as bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon) and zoysiagrass (Zoysia japonica)] grow best in the heat (typically in June, July, and August), and then turn brown (due to dormancy) over the winter (Table 1, Figure 2). Warm-season grass lawns are suited for the southern half of Indiana.

Annual grasses vs. perennial grasses

All grasses specifically planted for lawns are perennials. However, some annual grasses (such as crabgrass) can become lawn weeds.

Bunch-type grasses vs. spreading grasses

Bunch-type grasses (such as tall fescue) do not spread rapidly. Instead, each plant enlarges slowly over the years. A lawn of widely spaced bunch-type grasses will be thin because these grasses will not fill in and cover bare areas. Many common lawn grasses are spreading grasses with rhizomes or stolons (Figure 3). Because they will grow to fill in bare areas, spreading grasses are preferred for lawns. NOTE: Rhizomatous tall fescue cultivars are sold but current cultivars have short rhizomes often 1-2 inches long and behave more like a bunch-type with limited spreading capacity.

Figure 3. Parts of a turfgrass plant with below ground stems (rhizomes) and above ground stem s(stolons) shown. Bunch-type grasses lack stolons and rhizomes but produce tillers. Stoloniferous and rhizomatous grasses also produce tillers. Some grasses have stolons, rhizomes, and tillers are shown in this illustration.

Home lawn grasses vs. golf course turf

Some grasses (such as creeping bentgrass, Agrostis stolonifera) are only suitable for use in special situations such as golf course putting greens.

Turf Comparison

There are many important things to consider when selecting the right species to plant in the right place. Table 1 compares and contrasts these species and their various growth, establishment, and maintenance differences.

| Kentucky bluegrass | Perennial ryegrass | Tall fescue | Fine fescue* | Creeping bentgrass | Bermuda-grass | Zoysiagrass | |

| Region of adaptation | Statewide | Statewide | Statewide | North, Central | Statewide | South | Central, South |

| Growth habit | Rhizomes | Bunch-type | Bunch-type | Bunch-type* | Stolons | Stolons and Rhizomes | Stolons and Rhizomes |

| Growth rate | Moderate | Moderate | Fast | Slow | Slow | Fast | Slow |

| Heat tolerance | Fair | Poor | Good | Poor | Good | Excellent | Excellent |

| Stays green in a drought | Poor | Poor | Good | Fair | Fair | Excellent | Good to Excellent |

| Survives a drought | Good-Excellent | Poor | Good | Good-Excellent | Fair | Excellent | Excellent |

| Need to irrigate to maintain high quality turf | Very likely | Very likely | Moderately likely | Very likely | Completely likely | Not likely | Slightly likely |

| Rooting depth | Poor | Fair | Moderate | Fair | Fair | Superior | Good |

| Shade tolerance | Fair | Fair | Good | Excellent | Good | Poor | Fair |

| Winter hardiness | Excellent | Good | Good | Good | Excellent | Poor | Fair |

| Insect tolerance | Fair | Good | Good | Good | Fair | Fair | Good |

| Disease tolerance | Good | Poor | Fair | Good | Fair | Good | Good |

| Traffic/wear tolerance | Good | Fair | Good | Poor | Fair | Excellent | Excellent |

| Recuperative capacity | Good | Poor | Poor | Poor | Good | Excellent | Good |

| Turf color in summer | Medium to dark green | Medium to dark green | Medium to dark green | Medium green | Medium to blue green | Medium green | Pale to medium green |

| Winter color | Partially green | Partially green | Partially green | Partially green | Partially green | Straw-brown | Straw-brown |

| Leaf texture | Medium | Medium | Coarse | Fine | Fine | Coarse to Medium | Coarse to Medium |

| Maintenance Requirements | High | Moderate | Moderate | Low | High | Moderate to High | Low to Moderate |

| Annual nitrogen requirements (lbs N/1000 ft2) | 1-5 | 1-5 | 1-3.5 | 1-2 | 2-4 | 1-4 | 1-2 |

| Optimum mowing height (inches) | 2.0 to 3.5 | 2.5 to 3.5 | 3 to 5 | 2.0 to 3.5 | 0.125-0.75 | 0.5 to 2.0 | 1.0 to 2.5 |

| Mowing frequency | Moderate | Moderate | High | Low | Moderate | High in summer | Moderate in summer |

| Establishment methods | Seed, Sod | Seed | Seed, Sod | Seed, Sod | Seed, Sod | Seed, Sprigs, Sod | Seed, Sprigs, Sod |

| Optimum Seeding Window | Aug 15-Sep 15 | Aug 15-Sep 15 | Aug 15-Sep 15 | Aug 15-Sep 15 | Aug 15-Sep 15 | May 15-July 1 | May 15-July 1 |

| Days to germination | 8 to 21 | 5 to 10 | 6 to 10 | 7 to 14 | 7 to 14 | 7 to 21 | 10 to 21 |

| Seeding rate (lbs/1000 ft2) | 1.5 to 2 | 4 to 6 | 6 to 8 | 3 to 4 | 1 to 2 | 0.5 to 1.0 | 1 to 2 |

*Fine fescue is actually referring to a collection of fescue species, including strong creeping red fescue (Festuca rubra ssp. rubra), slender creeping red fescue (Festuca rubra ssp. littoralis), hard fescue (Festuca brevipilla), Chewings fescue (Festuca rubra spp. commutata), and sheep fescue (Festuca ovina). Creeping red fescues have rhizomes.

Selecting Improved Cultivars/Varieties

The term cultivar is short for cultivated variety. Both cultivar and variety refer to a plant with a specific characteristic or set of characteristics. Technically, a variety is a specific plant that occurs or is found in nature and a cultivar is a specific plant that was cultivated (traditional plant breeding) and selected by humans. Both terms get loosely used in the turfgrass industry and seed labels will often use the term variety despite the fact that almost 100% of commercially available turfgrasses are technically cultivars improved by turfgrass breeders.

What is important is that once you select a species to be planted, that you also select an improved cultivar of that species well-adapted to our region. Your local seed salesperson should be able to provide you information on which cultivars perform best and/or you can access this information, including how the cultivars performed in Purdue University testing, from the National Turfgrass Evaluation Program (www.ntep.org). Planting well-adapted, improved cultivars will improve turfgrass quality including color, reduce irrigation needs, reduce reestablishment and maintenance costs from pests, drought, or winterkill and ultimately increase sustainability. Bottom line is that new cultivars perform better and decrease maintenance costs.

Establishing Turf Species

Establishment of turf is most commonly accomplished with seed, although sod is commonly used in landscapes and new construction. Sod offers the advantage of “instant turf” whereas seed takes much longer to produce a green turf. Establishment with seed is much less expensive and is surprisingly less complicated than with sod. Regardless, it is important to understand the necessary installation steps. Following proper establishment procedures can produce a healthy turf that one can be proud of for many years to come.

The predominant planting method is seeding for cool-season grasses. All cool-season species and cultivars are options for planting whereas with sod, you are limited to what species and cultivars are being grown locally. Kentucky bluegrass is traditionally the most commonly sold cool-season sod in the Midwest because of its performance in our climate and because of its rhizomatous growth habit which helps to hold the sod pieces together after cutting. Tall fescue is being increasingly used and can be grown as sod but it must be netted or mixed with Kentucky bluegrass as it will not hold together well because of its bunch-type growth habit. Perennial ryegrass is not grown as sod because of its bunch-type growth habit and marginal adaptation in the Midwest due to its poor heat, drought, and disease tolerance. Strong and slender creeping red fescue and creeping bentgrass can be grown as sod but they may not be available commercially in Indiana.

Establishment Procedures

Prior to planting seed or sod, there are ten steps to follow for preparing the site for a successful seeding. Not all of these steps may be needed in all situations, but all are integral steps in the installation process.

- Test the soil for key information including soil pH, potassium, and phosphorous levels.

- Measure the lawn area. This will help you calculate how much seed, sod, or fertilizer you will need. When purchasing sod, plan on purchasing 10% more sod than the area to allow for cutting and trimming of sod pieces.

- If an installation site has perennial weeds or undesirable grasses, it is important to control these weeds before you install sod. Weeds like quackgrass and bermudagrass are nearly impossible to control in a lawn but they can be controlled with non-selective herbicide applications prior to planting.

- Remove all wood, concrete, pipe, rock, and construction scrap from an area before installing sod. You do not want these objects to interfere with turfgrass root growth and water movement.

- Grade the soil before planting by making sure the site’s surface is smooth and firm so that there are no areas where standing water may collect.

- Add topsoil if needed. This is especially important on sites with poor inherent soil fertility.

- Install any drainage or irrigation systems needed at the site.

- Apply any amendments to the soil prior to planting. A starter fertilizer (which is high in phosphorus but low in nitrogen and potassium) is a good choice when establishing a new lawn by seed or sod. Some sites may need an application of lime if the soil pH is <5.8.

- Prepare the site with a final grading to leave the soil surface smooth and ready for seeding or sodding. If sodding, do not install sod on excessively dry or hot soil.

- Prior to planting make sure that water is turned on at the site and that all irrigation heads are functioning properly.

Purchasing Seed

With grass seed you get what you pay for. High-quality seed is going to be more expensive than low-grade seed but it is worth the extra money. Some seeds come with additional tags and certification. There are three primary types of seed tags: white, blue and gold. Blue and gold tag certifications are not typical of seed sold commercially to homeowners but all seed sold does have a “white tag” that provides and guarantees that the test results are at or above those printed on the seed tag/label (truth-in-labeling). For high quality professional turf areas (e.g. sod and stadium fields or golf courses), blue and Gold tag certifications is desirable. High-quality seed contains less contaminants and has higher germination rates. The best way to obtain good quality seed is to buy reputable seed from a respected supplier.

Grass seed often comes packaged as a mixture of several kinds or a blend of cultivars. In some cases, you may get two or more species (different kinds) mixed together. In others, you may get one species but a blend of several cultivars (different cultivars). These blends of cultivars and mixtures of species are preferred over grass seed of only one cultivar, since there is a greater chance one of the grasses will thrive in the lawn. Each grass cultivar or species in the mixture will prefer slightly different conditions — and the lawn is a collection of slightly different conditions. Further, if the front yard is sunny and the backyard is shady, plant the appropriate grasses in each location rather than a mixture everywhere. Select the grass seed for your lawn based on site conditions, expected use, and the level of care you are willing to give the lawn. Use Tables 1 and 2 to select the best grass seed for your application.

Planting Date

The best time to seed a cool-season lawn is in the late summer to early fall. Adequate soil moisture, warm soil, and limited weed pressure allow for excellent seedling growth. Between August 15 and September 15 is optimum seeding window. It is critical to seed as early as possible within this window. Even when seeding within this window, waiting one week later to seed may mean the turf will take 2 more weeks to mature as germination and subsequent growth slows later in the fall as temperatures cool.

Seeding in spring is very difficult and often unsuccessful with certain turf species. Kentucky bluegrass planted in the spring almost always fails due to its slower establishment rate and competition from weeds. Summer seeding should be avoided. Areas seeded in summer will succumb to heat and drought stress because of their limited root systems and be out-competed by summer annual weeds resulting in a thin turf.

As with seeding, fall is the optimum time of year to establish cool-season species such as tall fescue and Kentucky bluegrass from sod. A fall planting date will allow adequate time for the roots to develop prior to the next summer. Lawns sodded in the spring and summer will not survive droughty conditions well the first year. Additionally, lawns sodded in the heat of summer (when temperatures exceed 90°F) may not grow any new roots until air and soil temperatures cool. For these reasons, it is essential to provide proper irrigation for summer-established sod until the turf can establish a new root system. Due to construction deadlines, it is sometimes necessary to install sod during the winter. Dormant sodding can be successful but is more risky than fall sodding due to the increased risks of winter desiccation and injury.

| Light | Maintenance Type | Species | Seed Rate(lbs/1,000 ft2) | Notes |

| Full sun | Home lawn — medium-high maintenance (regular mowing, 3-4 pounds of actual N per 1,000 ft2 per year, irrigation) | 100% Kentucky bluegrass blend† | 1.5-2 | Plant a blend of cultivars/varieties |

| 80-90% Kentucky bluegrass + 10-20% perennial ryegrass mixture‡ | 3-4 | Limit perennial ryegrass wherever possible to reduce disease problems | ||

| 100% turf-type tall fescue blend | 6-8 | Do not plant Kentucky 31 tall fescue. Choose improved cultivars. | ||

| Home lawn — low maintenance (mowing, 1-2 pounds of actual N per 1,000 ft2 per year, limited irrigation) | 100% turf-type tall fescue blend | 5-8 | Do not plant Kentucky 31 tall fescue. Choose improved cultivars. | |

| 90% turf-type tall fescue + 10% Kentucky bluegrass mixture | 5-7 | Similar appearance to 100% tall fescue lawns but contains Kentucky bluegrass to help with stress recovery | ||

| Temporary cover needed | 100% annual ryegrass | 4-5 | Plan on reseeding in the next 12 months | |

| Roadsides, parking areas, low maintenance | 100% turf-type tall fescue blend | 8-10 | Kentucky 31 forage-type tall fescue can be used as an alternate to turf-type tall fescues | |

| 60% turf-type tall fescue + 30% Strong creeping red fescue + 10% Kentucky bluegrass mixture | 5-7 | Similar but different than the current recommended INDOT mixture. Textures are contrasting but survival to different environments is high. |

† A blend is when more than one cultivar/variety of the same species are combined together to enhance the performance of the turf (i.e. improved disease, drought, or heat resistance or improved color, texture, density, etc.).

‡ A mixture is when two or more species are mixed together in a seed lot to take advantage of the different growth characteristics of the species.

| Dry site, moderate shade, central and northern Indiana | Dry site, moderate shade, southern Indiana | Moist, shaded site, central and northern Indiana | Moist, shaded site, southern Indiana |

|

|

|

|

† Should include a blend of cultivars.

Warm-Season Turf Establishment

Bermudagrass and zoysiagrass are traditionally established by sod or sprigs (pieces of rhizomes and stolons) but certain cultivars can be seeded. Seeding and sprigging should be done in May or June to allow sufficient time in summer for establishment prior to winter. Weed encroachment will be a problem when establishing warm-season grasses from seed as many weeds germinate during early summer. The planting window for sodding warm-season grasses is slightly wider than for seeding or sprigging in Indiana, but sodding should be done in late spring or summer for best results.

Warm-season turfgrass sod availability is limited to southern Indiana sod producers and seed can be acquired from local suppliers or online. Regardless or planting method, it is important to choose a cold hardy cultivar of these warm-season grass species because of our severe winters in Indiana. Both cold hardy seeded and vegetative (sprigs or sod) cultivars are available but unlike with cool-season grasses, the cultivars available by seed are not available by sod and vice versa because of how warm-season grasses reproduce.

When seeding, sprigging, or sodding turf, weeds will often germinate with the desirable turfgrass. Removing weed competition in newly planted turf is important to allow for proper turf establishment. Once the turf is established and irrigated, mown, and fertilized properly, weeds will be less problematic. While some herbicides can be applied safely before planting or a few weeks after the planting, most cannot. Follow label directions on when to safely apply herbicides to newly planted turf.

Irrigation

Though turfgrasses perform best with enough regular irrigation during the summer to keep them green and growing, they are very capable of surviving on natural rainfall without irrigation. Turfgrasses perform much better under slightly dry conditions than under wet or saturated conditions. Some research indicates that turf actually needs less water to survive than trees. However, lawns are often branded as water consumers. The reality is that lawns don’t need a lot of water to survive, but that people over-water lawns.

The first sign of drought stress is that your green turf will start to turn a purplish/dark green color. This is called wilting. The leaf blades will appear much thinner when wilted because the leaf blade has curled or folded up to conserve moisture (Figure 4). Foot-printing is another visual symptom of drought. Foot-printing is when the turf does not bounce back quickly after walking across a lawn due to a lack of moisture (turgor) in the leaves (Figure 5). After a few days of drought stress your lawn will start to turn brown. If drought continues, portions or all of the turf may turn a brown color and enter into drought (summer) dormancy.

Figure 5. Foot-printing is a first sign of drought stress. Foot-printing is when the turf does not bounce back quickly after walking across a lawn due to a lack of moisture (turgor) in the leaves.

Look for drought stress first in these areas:

- On slopes

- Under trees

- Newly planted turf

- Shallow rooted turf

- Drought sensitive species

- Compacted soils

- Along sidewalks, curbs and driveways

Turf species respond to drought differently through various mechanisms. Some species have the ability to survive the drought well even though they might not stay green during a drought (Figure 6). This is called summer dormancy. Turfgrass dormancy (brown turf) is a mechanism allowing survival under suboptimum growing conditions. Summer turf dormancy allows survival with little irrigation/precipitation without significant thinning upon recovery from dormancy. Kentucky bluegrass uses this dormancy mechanism to survive drought and it can survive 6-8 weeks with no irrigation during a drought. Survival of dormant turf is best when there is no regular traffic, good soil, well-established turf, and when there is minimum thatch (a layer of undecomposed organic matter between the turf and the soil surface).

Figure 6. Assessment of species performance following a moderate drought. Notice the variable performance of different species.

The drought tolerance mechanism for other species is not to enter dormancy but instead to resist drought through deep rooting. Tall fescue is more deeply rooted than Kentucky bluegrass and it can remain green during moderate drought stress. Despite these two differing mechanisms, both tall fescue and Kentucky bluegrass survive drought well in Indiana and under extreme drought, Kentucky bluegrass has the potential to survive longer droughts than tall fescue as rhizomes can escape water stress by surviving in dry soils until rainfall returns (Table 1).

Among the turfgrasses used in Indiana, bermudagrass can survive dry soil conditions best. Zoysiagrass might be listed next and followed by Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue. Regarding watering requirements (amount) to maintain quality during drought, research shows that bermudagrass generally requires less irrigation than zoysiagrass. Both bermudagrass and zoysiagrass need less irrigation than tall fescue. Tall fescue needs less irrigation than Kentucky bluegrass to remain green during drought. Within species there is also significant variability among cultivars with some having superior drought tolerance.

Deciding to water or not during drought

- Indiana rarely has chronic (long-term) drought conditions but it is common for us to encounter acute drought (droughts of <3 weeks in duration).

- Turf will enter a drought induced dormancy when there is no rainfall for a period of more than 2 weeks, temperatures are high, and humidity is low.

- Some species like Kentucky bluegrass may enter drought stress quickly but will recover well due to this dormancy, which conserves water, and the ability to regrowth from rhizomes. Other species like tall fescue will stay green longer during drought due to their deeper root system but these species are more likely to succumb to moisture stress and die in chronic or long-term drought conditions.

- Many low-use turf areas can be allowed to go dormant during droughts, especially where water supplies or infrastructure is limiting.

- Turfgrasses that are trafficked during drought conditions such as golf courses and athletic fields must be irrigated regularly to maintain performance, prevent widespread turf damage, to maintain safe conditions for athletes, and/or to protect economic interests.

- Turf swards less than a year old should also be irrigated because they have not yet developed extensive root systems.

Advice if you choose to water during an acute drought

- Start first by watering only the drought stressed areas (hot spots).

- Water deeply. Since all turfgrasses perform better on the dry side, water to ensure that the soil is moist to the depth of the majority of the roots (about 4-inches into the soil) and then don’t water again until you see the turf wilting in the heat of the afternoon (the first sign of drought stress).

- Water infrequently. Make it your goal to maximize the number of days between irrigation cycles. You will likely be surprised on how long the turf can go without signs of drought stress. In a normal year, watering your lawn once or twice weekly during periodic dry periods will often be sufficient, but during longer periods of drought coupled with high heat and low humidity, turf may need watered more often to remain green and growing.

- Increase the efficiency of your irrigation system by using a rain sensor with automatic irrigation systems to prevent watering during or after rain events. Also use the irrigation budgeting features of your irrigation control system to replenish water based on evapotranspiration losses.

- Check your irrigation system for improperly aligned sprinklers, non-turning sprinklers, evenness of distribution, etc. This is true for automatic as well as hose-end sprinklers. This will improve the efficiency of irrigation and cut down on water use.

- Water between 4:00 am and 8:00 am to improve efficiency because of less evaporation and wind distortion. Irrigating in early morning does not increase disease.

- Cultivate with hollow tines (core aerification) in the spring and fall during periods of active growth to improve water penetration into the soil, relieve soil compaction, and to help create a deeper root system.

Advice if you choose not to water and let your turf enter dormancy

- Stay off the turf! Limit traffic (including mowing) to minimize crushing of the turfgrass leaves and crowns.

- Water once every 4 weeks during extreme drought with 0.5- inch of water to keep turf plant crowns hydrated. This amount of water should not green up the turf, but it will increase its long-term survival.

- Turf will likely become weedier. Avoid the temptation to apply herbicides even though weeds are more obvious in a dormant (brown) lawn. Herbicides are less effective on drought-stressed weeds and can be damaging to drought-stressed turf.

- Apply a slow-release nitrogen fertilizer prior to the end of the drought or when sufficient rainfall returns to enhance turf recovery.

- Turf should recover in 1-2 weeks after significant rainfall returns. New growth from the crowns will be visible. Reestablishment may be needed if some recovery is not visible after 2 weeks, especially if you have a bunch-type turf species (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Drought injury to perennial ryegrass. Reseeding will be necessary to repair this area since perennial ryegrass is a bunch-type and not a spreading grass.

Mowing

The primary purpose of mowing is to improve its appearance but there are other benefits. Proper mowing technique, equipment, frequency, and height will improve the quality of a turf while also increasing the health of the turfgrass plants and decreasing weeds.

Mow as often as needed to never remove more than 1/3 of the leaf blade in a single mowing. In other words, if your mower is set at 3 inches, mow before your lawn reaches 4.5 inches high. Removing more than 1/3 of the leaf blade in a single mowing is detrimental to plant health.

In general, mowing turf at higher mowing heights helps increase overall plant health and reduces weed competition. A range of mowing heights for each species is provided in Table 1. Some species need mown taller than others. Higher mowing heights allow the plant to produce more energy via photosynthesis and a deeper rooting system as well. Conversely, mowing too low will cause a rapid decline in turf health, decreased turf density, and increased weed encroachment.

When you mow regularly at the proper height, your lawn is improved by recycling grass clippings and the nutrients they contain. Leave the clippings on the lawn to break down and return valuable nutrients to the soil. If you allow the turfgrass to grow too long between mowing, excessive clippings left on the surface can smother and damage your turf. If you get behind on mowing due to weather or taking on a new client with a tall lawn, rake the clumps or mow over the property a second time when dry to breakup the clippings into smaller pieces. Mowing frequently and when the grass is dry will prevent clumping. Leaving clippings on the lawn is an easy way to reduce waste and recycle nutrients. It takes less time than bagging the clippings, too.

There are two main types of lawn mowers used: reel and rotary. Reel mowers have many parts including a reel, bedknife, and a roller. The grass blade is cut in a scissor-like fashion when the leaf blade is pinched between the reel and the bedknife. Reel mores provide a more precise cut and are used in high quality areas such as golf courses.

Rotary mowers are by far the most popular type for taller heights-of-cut. Rotary mowers work by cutting the grass blades in an impact, machete type cut. This cut is less precise and often more damaging to the leaf blade. The potential to scalp turf is higher when using a rotary mower, but the height of cut is easy to change and blades are easy to sharpen.

Sharply cut leaf blades increase turf health by improving recovery, decreasing water loss, and increasing photosynthesis. Turf mown with a dull mower blade have poor aesthetics, heal more slowly and have greater water loss (Figure 8). Sharpen blades often.

Figure 8. Leaf blades cut by a dull mower blade. The white tissue sticking out of the leaf blades is the vascular tissue of the plant. Sharpen mower blades if you observe this leaf shredding.

Traffic Management

Regular traffic that occurs on sports fields, golf courses, and residential turf can be detrimental to turf growth and increase susceptibility to certain pests.

Regular traffic from athletes, vehicles, and equipment can

- Decrease turf density

- Increase soil compaction

- Decrease rooting

- Wound turfgrass leaves causing physical injury

- Decrease photosynthesis

- Decrease turf recovery

- Encourage the encroachment of weeds

How well the turf recovers from damage will be based on the turfgrass species, the severity of the damage, the fertilization program utilized, the age of the turf, the growth rate of the turf, and the growth habit of the turf species. The functional quality of the turf including its capacity to tolerate traffic based on leaf rigidity and elasticity as well as the verdure (mowing height) will determine how quickly the leaves wear. Short mown areas wear more quickly as does young (<6 months) turf.

Kentucky bluegrass is recommended for use in high traffic areas in the northern two-thirds of Indiana because of its good traffic tolerance and ability to recovery from rhizomes following injury. Bermudagrass is the preferred species for high traffic areas in the southern one-third of Indiana because it has excellent traffic tolerance and recuperative capacity. While some turfgrasses such as tall fescue have good traffic tolerance, its inability to spread and recover from its bunch-type growth habit makes it undesirable for use on athletic fields with moderate to high traffic.

Encouragement of growth through irrigation and fertilization following traffic will increase recovery. Seeding of thin areas will help reestablish a dense canopy able to handle additional traffic. Lastly, soil cultivation through core aerification will help decrease soil compaction and increase water infiltration and encourage the development of new roots.

Fertilization is Key to Maintenance

Proper nutrition through fertilization is fundamental to turf maintenance. We have discussed in this chapter the difference between warm-season and cool-season grasses and differences in growth habit between species. These species and growth habit differences must be taken into consideration when developing a fertilization program. This chapter also discusses how to establish turf with a focus on planting date, but fertilization of newly planted turf is just as crucial as planting date to optimizing establishment.

Whether or not turf is irrigated as well as recent rainfall amounts will greatly impact how turf grows and when fertilization should be timed to enhance turf health prior to drought, turf response during drought, and turf recovery following drought. Mowing frequency is highly influenced by turf fertilization as well as traffic injury and recovery. Susceptibility to pests and environmental stresses is also heavily influenced by plant nutrition. Because turf nutrition and fertilization is central to turf maintenance, it is discussed in detail in this next section.

Overview

Keeping turf healthy requires careful implementation of several key cultural management practices such as mowing, irrigation, and fertilization. Healthy turf provides aesthetic, recreational, and environmental benefits. Well-maintained turf and landscapes not only significantly increase property values, they also build a strong source of community pride (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Proper fertilization is key to enhancing the health of the turf and enhancing the aesthetic, environmental, and recreational benefits that turf provides.

Periodic fertilization of an established turf is important because it improves turf health and can help to decrease weed, insect, and disease pests — that saves you money and is environmentally responsible. Further, fertilization provides needed nutrition to increase turf traffic tolerance and recovery from injury and to protect water quality when done appropriately. This next section on fertilization answers questions about fertilizing cool-season turf and provides tips for creating your own fertilization program.

What Kind of Grass Is in Your Turf?

Most turf in the Midwest contain cool-season grasses, which grow best in the cooler temperatures of spring and fall. During the hottest times of year, they may grow very slowly or even enter summer dormancy in times of drought. Kentucky bluegrass, perennial ryegrass, tall fescue, and fine fescues are common cool-season turfgrasses. By contrast, warm-season grasses perform best in warmer climates and are less common in the Midwest, except near the Ohio River valley. These grasses thrive and grow in summer when many cool-season cultivars go dormant. Zoysiagrass and bermudagrass are common warm-season turfgrass species. Since grass species need differing amounts of fertilization (Table 1), identification is the first step in developing a proper fertilization program.

Why Should You Fertilize Your Turf?

Fertilizing turf with the right nutrients helps maintain density and plant vigor, enhances green color, and encourages growth and recovery from turf damage and seasonal turf stresses (such as hot, dry periods). Unfertilized turf will gradually lose density. When that happens, undesirable grasses (such as crabgrass) and broadleaf weeds (such as dandelion and white clover) encroach and the risk for soil erosion increases. Properly fertilized turf better tolerates stresses such as heat, drought, and cold. Applying the right fertilizer at the correct time helps turf plants accumulate and store the essential plant foods (sugars/carbohydrates) that are used for growth and development.

Malnourished turfgrasses are also more prone to mechanical damage from traffic and also damage from diseases and insects — the damage is more noticeable and recovery takes longer (Figure 10). In short: dense, healthy, properly fertilized turf requires fewer pesticides to manage weeds, diseases, and insects. Turf receiving periodic fertilization also helps protect water quality by substantially reducing water runoff and potential soil losses (Figure 11).

Figure 10. The Kentucky bluegrass and perennial ryegrass turf in this picture has not been fertilized for several years and contains white clover and rust disease. The turf quality is poor from a lack of density and uniformity in addition to the pests present.

Figure 11. The Kentucky bluegrass turf in this picture has been regularly fertilized and its increased density allows it to out-compete weeds.

What Nutrients Does Your Turf Need?

You should only apply the nutrients your turf needs. The nutrients plants need in the greatest quantity are nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). Of these three, N has the most impact on turf. Nitrogen promotes green color and overall growth, especially leaf growth which is important for turfgrass. Plants need phosphorus and potassium for strong root and stem growth, which is most crucial when establishing new turf. However, turfgrasses have fibrous roots systems that allow them greater access to P and K in the soil that many ornamental plants. As such, turf needs little P and K fertilization once turfgrass becomes established in our typical silt loam or silty clay loam soils. One exception is that turf often needs more K fertilization when grown in sandy soils such as those in golf course putting greens or those in northern Indiana.

Don’t guess the nutrient needs of your soil: you should test your soil to determine what nutrients it needs. Soil tests estimate the nutrient availability of the soil. Turfgrass plants accumulate 13 essential nutrients from the soil (P, K, N, S, Ca, Fe, Mg, B, Mn, Cu, Zn, Mo, Cl). You will not need to fertilize for most of these nutrients because they are already present in the soil in sufficient quantities for healthy turf. Plants also need carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) but they obtain these freely from air and rainfall.

Soil test results also indicate soil pH, which is the acidity or alkalinity of the soil. If the pH is too high or too low, it will limit nutrient availability and turf growth, and will reduce turf health. Poor soil pH must be corrected or certain micronutrients may need supplemented in high pH soils.

Select an appropriate fertilizer source based on soil test results (Table 4) and your color and growth preferences (Table 5, 6). While soil tests recommend how much of nutrients like phosphorus and potassium that your soil needs, there is no reliable soil test to determine the N needs for turf. Nitrogen is applied to provide greening, enhance plant food production, and encourage growth and development. Individual needs will vary depending on personal color preferences, the turf’s need to recover, and its ability to maintain itself.

| Soil K ≤ 50 ppm | Soil K > 50 ppm | |

| Soil P ≤ 25 ppm | Choose products that are high in P and K. Fertilizers with high P and K ratios (examples include: 10-20-10, 10-10-10, 13-13-13, 19-19-19). | Choose products that are high in P and low in K. Fertilizers with high P and low K ratios (examples include: 18-24-6, 20-27-5) or no K (examples include: 6-2-0). |

| Soil P > 25 ppm | Choose products that are low in P and high in K. Fertilizers with low P and high K ratios (examples include: 22-3-14, 26-2-13) or no P (examples include: 22-0-5, 16-0-8). | Choose products that are low in P and K. Fertilizers with low P and K ratios (examples include: 11-2-2, 27-3-4, 29-3-4, 29-2-5, 35-5-5) or no P or K (examples include: 21-0-0, 46-0-0). |

How Do You Develop a Fertilizer Program?

An annual fertilizer program generally consists of two to six individual fertilizer applications. Base your annual fertilizer program on the specific goal to maximize turf health, not a color response. If you want the greenest, most actively growing turf all year round, it is important to understand that you will likely need to apply more fertilizer more frequently (four to six times annually). Remember, where you apply more N, you will need to mow more often.

If your primary goal is a very dark green turf, consider selecting and planting grass cultivars that are genetically darker green (Figure 12). Selecting turfgrass cultivars with improved turf color may help reduce the amount you need to spend on fertilizer and decrease your mowing requirement.

Figure 12. The new and improved turf-type tall fescue cultivar on the left has a darker green color, improved density, a narrower leaf, and overall improved turf quality which make it more desirable for a managed turf than older forage-type Kentucky 31 cultivar on the right.

When Should You Fertilize?

The cool-season grasses (such as bluegrasses, fescues, and ryegrasses) will benefit most when you apply the majority of N fertilizer from late summer through fall (Figure 13). This promotes summer recovery, enhances shoot density, maximizes green color, and prepares the turf for winter, all without a growth surge.

Figure 13. This illustration shows the seasonal growth pattern of cool-season grass shoots and roots. Note the suggestions for when to apply N to promote maximum turf health.

Apply less N during the spring growth flush, and then apply little to none during summer except where you frequently water and/or regularly remove clippings during mowing.

When you apply N fertilizer during the spring, use slow-release fertilizers to minimize excess growth. To promote maximum density during late summer and early fall (late August through early November), you should apply up to 1 pound of N per 1,000 square feet each month. From early October until early December, apply primarily water-soluble N fertilizers at slightly lower rates (such as 0.5 to 0.75 pound per 1,000 square feet).

The warm-season grasses (such as bermudagrass and zoysiagrass) will benefit most when you apply the majority of N fertilizer from late spring after green-up through summer with the last application no later than mid-September. This late spring and summer fertilization promotes recovery from winter, enhances shoot density, maximizes green color, and prepares the turf for winter.

What Fertilizer Should You Use?

There are many commercially available fertilizer products. By law, all fertilizers list three numbers on their labels (for example, 16-4-8). These numbers indicate the guaranteed minimum percentage nutrient analysis or amount of total nitrogen, phosphorus (as available phosphate), and potassium (as soluble potash). For example, a bag of 16-4-8 fertilizer contains 16 percent N, 4 percent P, and 8 percent K. These nutrients are always listed in the same order on the fertilizer analysis, N-P-K.

Consult your soil test report to determine your specific phosphorus and potassium needs. Many consumer publications suggest applying phosphorus and potassium in the fall to “put the turf to bed.” However, if a soil test indicates your soil has sufficient phosphorus and potassium, applying more is unnecessary.

Ideally, you should use “turf” fertilizers. Avoid “general-purpose” garden fertilizers (such as 12-12-12). Turf fertilizers are specifically designed to provide the nutrients that mature turf needs. They also are formulated to minimize turf injury and often contain some portion of slow-release nutrients to provide long-term, steady feeding.

Calculating Granular Fertilizer Needs

To determine how much fertilizer you need to apply you need to know three important things:

- The size of the area you plan to treat

- The target application rate you want to apply (normally between 0.5 and 1.0 pound of actual N per 1,000 square feet)

- The percentage of the nutrient in the fertilizer product you will use

Question: Let’s say you have a lawn that is 5,500 square feet, your target application rate is 0.75 pound of actual N per 1,000 square feet, and you are using an 25-0-10 fertilizer product. Here’s how you determine how much actual fertilizer product you will need to apply to your lawn.

Step 1. Convert the percentage of the nutrient to a decimal. The 25-0-10 fertilizer product contains 25 percent N, so the decimal value is 0.25.

Step 2. Divide the target application rate (0.75 pound) by the decimal value from step 1.

0.75 ÷ 0.25 = 3.0

This is how many pounds of actual fertilizer product you will need per 1,000 square feet.

Step 3. Divide the actual area of your lawn (5,500 square feet) by 1,000:

5,500 ÷ 1,000 = 5.5

Step 4. Multiply the results from Steps 2 and 3 to determine how much actual fertilizer you will need to apply to your lawn at the desired rate:

3.0 x 5.5 = 16.5

Answer: You will need to apply 16.5 pounds of 25-0-10 fertilizer product to your 5,500-square-foot lawn to achieve the target application rate of 0.75 pound of N per 1,000 square feet.

Two Primary Categories of Nitrogen Fertilizers

Nitrogen fertilizers come in many colors, shapes and sizes but they are broadly classified into two categories (Table 5):

- Quick-release products that are water-soluble and immediately available to plants

- Slow-release products that release N slowly over time and become available to plants. They are usually water-insoluble.

One type of fertilizer is not necessarily better than the other — what you apply often depends on your goals and when you plan to apply. Most turf fertilizers combine quick- and slow-release N sources together in a single bag. Fertilizer labels will describe the specific proportions of each type the product contains.

For established turf, it is appropriate to apply fertilizers that contain 25 to 50 percent slow-release N. This combination promotes both rapid greening and gradual feeding for several weeks. However, from early October through late November (prior to the ground freezing) a product that contains nearly 100 percent water-soluble (quick-release) N is preferred.

| Quick-release (readily available, water-soluble) | Slow-release (not immediately available, controlled release, usually water-insoluble) |

| Examples | Examples |

|

|

| Characteristics | Characteristics |

|

|

Should I Apply Liquid or Granular Nitrogen Sources to the Turf?

Nitrogen uptake occurs in both the turf leaves and roots. Uptake of nitrogen from foliar/liquid applications is primarily through the leaves and N uptake is primarily through the roots from granular applications. Either application method (liquid or granular) can result in feeding the plant, but there are things to consider when choosing which method of application to use.

Liquid applications (sometimes called foliar applications) can be made by dissolving water soluble N sources such as urea in water or by using commercially available, N-containing, liquid fertilizers. Liquid applications are common when a “light” rate of nitrogen is desired such as 0.25 pound of N per 1,000 square feet. Rates of up to 0.5 pound of N per 1,000 square feet can be applied as liquid. Liquid applications are especially beneficial to turf with a damaged or limited root system such as putting green turf in summer months as N uptake is through the foliage.

One major drawback to liquid fertilization is that fertilizer burn is more common. Fertilizer burn is a drying out or browning of leaves from fertilizer salts. Liquid fertilizers have more potential to burn foliage than granular applications as a liquid application applies the fertilizer directly to the leaf unlike granules that typically fall to the soil surface when applied. Liquid applications during hot and dry conditions increase the risk of foliar burn. The higher the rate of fertilizer, the higher the risk of burning turf.

Granular applications can be made with both quick- and slow-release N fertilizers. It is difficult to apply low rates of N with granules except by organic fertilizers, which contain a low percentage of nitrogen. Higher rates of N can be applied with granular fertilizers, especially those containing slow-release N. Select the granule (particle) size based on the application site: small granules for short-cut turf like putting greens and larger granules for lawn height turf.

Blended and homogenous granular fertilizers available. Each particle in a homogenous fertilizer contains the nutrients guaranteed in the analysis. Blended fertilizers are simple mixtures of different dry fertilizers ingredients. Both blended and homogenous fertilizers can be used to fertilize turf successfully.

How Much Should You Apply?

All turf will benefit from some fertilizer. Fertilization, especially with N, helps maintain density, color, and vigor. But more fertilizer is not necessarily better and excess fertilizer could lead to surface and ground water contamination.

Annual N requirements vary considerably depending on turfgrass species, growing environment, appearance expectations, and traffic. When considering how much N to apply, you must answer two questions:

- How much overall fertilizer do you need to meet your expectations?

- How will this amount affect your turf maintenance? For example, are you willing to provide the extra mowing that might be required?

In general, mature cool-season turf may need between 1 and 5 pounds of actual N per 1,000 square feet per year depending on your goals (Table 6) and other site factors (Table 7). Selecting the specific fertilizer, rate, and timing for each application also depends on many factors such as the time of year and the composition of the fertilizer.

| Desired Maintenance Level | Early Spring (mid-March-April) | Spring (May-mid-June) | Summer (mid-June-August) | Early Autumn (late August-Sept) | Autumn (Oct-early Dec) | Total Annual Nitrogen |

pounds of actual nitrogen/1,000 square feet | ||||||

| Low | 0-0.5 | 0-0.5 | 0 | 0.5-1.0 | 0-1.0 | 1-3 |

| Moderate | 0-0.5 | 0.5-0.75 | 0 | 0.5-1.0 | 0.75-1.5 | 2-4 |

| Moderate + Irrigation | 0-0.5 | 0.5-1.0 | 0-0.75 | 0.5-1.0 | 0.75-1.5 | 2-4 |

| High + Irrigation | 0-0.5 | 0.5-1.0 | 0.5-1.0 | 1.0-1.5 | 0.75-1.5 | 3-5 |

When making each application, the rate depends primarily on the amount of quick-release (water -soluble) N it contains. Do not apply more than 1.0 pound of actual quick-release N per 1,000 square feet in any single application. This helps minimize growth surges, potentially negative effects (such as leaf injury), and leaching and runoff loss. Remember, your goal should be steady, sustained growth, not rapid growth flushes or greening.

If the fertilizer product contains more than 50 percent of its N from slow-release sources, you can apply the product at higher rates. For these products do not apply more than 2.0 pounds of actual N per 1,000 square feet in any single application.

In other words, if a product contains 50 percent slow-release N, applying the product at 2.0 pounds of actual N per 1,000 square feet supplies 1.0 pound per 1,000 square feet each of quick-release (water-soluble) N and slow-release N.

What Else Should You Consider?

Growing environments, site use, age, and other management practices affect overall N needs. You should adjust your annual fertilization program based on the age, shade, traffic level, irrigation or mowing practices of the site. See Table 7 for more examples of how to adjust fertilization programs based on the goals, conditions, environment, etc. at your location.

Common adjustments:

- New turf (seeded or sodded), turf may require 20-50 percent more overall N and more frequent applications than well-established turf during the first nine months after planting.

- Turf that is fully mature and has been regularly fertilized for more than 10 years doesn’t need as much N fertilizer. Over time, the soil under mature turf has accumulated organic N, which provides background nutrition. For mature turf, consider omitting one or more applications or reducing application rates to meet your growth and color goals.

- Returning clippings during mowing benefits the turf because grass clippings contain valuable nutrients that can be recycled into the soil. If you must regularly remove clippings when you mow, you may need to increase the amount of N you apply each year by 25 to 50 percent to maintain growth and color.

- Shaded grasses grow more slowly, so they may require up to 50 percent less annual N than turf grown in full sun. In general, do not apply more than 2.0 pounds of actual N per year to turf in shaded environments. You can apply fertilizer at the same times you would apply it to sunny turf, but you should simply reduce the overall N application rates by half. The turfgrass species of choice for shaded areas are the fine-leaf fescues such as Chewings fescue or strong creeping red fescue. This grass will persist in moderate shade, but if you apply too much N, the stand’s quality and density will decline.

| Quality and Expectations | Adjustment of nitrogen application rate/frequency |

| Age of the turf (or soil) | Typically, less nitrogen is needed turf that has been well-maintained for many years. This is because well-maintained turf stores more organic nitrogen in the soil. Newly planted areas need additional nitrogen (≤50% more) to promote establishment. |

| Clipping removal | Returning clippings causes an annual increase of about 1.0-2.0 lb N/1000ft2. Therefore, we recommended returning clippings to enhance turf and soil health. If clippings are removed, N fertilization should be increased. |

| Use (traffic) | Fertilization will need to increase to help turf recover from traffic injury such as on athletic fields. |

| Irrigation | Irrigation increases plant growth. Irrigated turf may need some additional fertilization. Do not over irrigate. |

| Species and cultivar | Tall fescue requires less (~25% less) nitrogen fertilization than Kentucky bluegrass. Zoysiagrass needs less (~50% less) nitrogen fertilization than bermudagrass. |

| Climatic conditions (weather) | If weather is not favorable to turfgrass growth, less fertilizer will be needed or fertilizer application timing should be adjusted. |

| Length of growing season | If growing conditions are favorable for longer periods of time, additional fertilization may be necessary. As such, a Kentucky bluegrass lawn in Northern Indiana would require slightly less nitrogen fertilization than a similar lawn in Southern Indiana. |

| Soil conditions (texture, cation exchange capacity) | Sandy soils are not as capable of holding nutrients; Use slow-release fertilizers on sandy soils or apply lighter more frequent fertilizer applications. Alternatively, soils with high quantities of organic matter need less nitrogen fertilization. Reduce the total annual N applied by 20% or more. |

| Site specific conditions (shade, etc.) | Turfgrass growth is reduced in shade so fertilization should also be reduced 25-50% in shady areas. |

| Diseases | Some turfgrass diseases are exacerbated by too little or too much fertilization. |

| Recuperative needs | Turfgrass damaged by drought stress or traffic may need additional fertilization to help recuperate. |

| Budget | If budget is limiting, use more frequent applications of a quick-release fertilizers at lower rates or reduce the total annual N applied. A reduction in total N fertilization will likely be followed by increased weed encroachment. |

More Tips for Responsible Fertilization

Healthy turf provides more than aesthetic beauty. A substantial amount of university research has demonstrated that properly maintained and fertilized turf considerably reduces water runoff, soil sediment, and nutrient losses. The movement of sediment and nutrients like N and phosphorus from urban areas, agricultural fields, and turf has been implicated in poor water quality. However, research demonstrates that turf has a positive impact on maintaining water quality primarily through reducing soil erosion and that proper fertilizer application aids in water quality protection.

Follow these additional suggestions to fertilize your turf responsibly to maximize health and minimize nutrient loss.

- Mow as high as practically possible (3.0 inches or taller) to promote deep rooting and greater access to more soil nutrients. Return clippings to increase turf and soil health.

- Apply lower rates of fertilizer more frequently (such as 0.5 pound of actual N per 1,000 square feet every 21 days). This practice may provide more consistent color and growth responses than less frequent applications at higher rates.

- Only apply fertilizers to actively growing turf. Do not apply quick-release N fertilizers to dormant or severely drought-stressed turf. Do not apply any fertilizer during the winter or when the soil is frozen.

- Use a rotary spreader when possible (Figure 14). Rotary spreaders may be less time-consuming, easier, and provide more uniform product coverage than drop-type spreaders.

- Clean up any fertilizer particles that end up on hard surfaces (sidewalks, driveways, roads, etc.) (Figure 15). Return the particles to the turf using a broom or blower to protect surface waters.

Figure 14. Rotary spreaders are the most accurate way to uniformly apply granular fertilizers. Here a ride-on spreader/sprayer is shown.

Figure 15. Be sure to sweep or blow fertilizers off of sidewalks, drives, and other impervious surfaces back into the turf after an application so that it will not contaminate surface waters.

Cultivation and Thatch Management

The term cultivation has a different meaning in the turf industry than it does in traditional agriculture. In agriculture, the term refers to the tilling of the soil. Cultivation in the turf industry refers to a variety of mechanical processes that are used to loosen the soil and reduce compaction, reduce thatch, or groom the surface.

Figure 16. Aeration removes small columns of soil (cores) from the lawn and helps reduce soil compaction, reduce thatch, improve rooting, increase water infiltration, and increase soil aeration.

Core aerification or coring is one of the most effective cultivation practices to reduce both thatch and soil compaction. Aerification is the process of removing small columns of soil (called plugs or cores) from your lawn to decrease soil compaction and increase air and water movement in the soil (Figure 16). Aerification improves the health of the turf, especially turfgrasses growing in compacted or heavy clay soil or heavily trafficked areas. Aerification can also help reduce thatch.

Aerification machines (aerifiers) work best when the tines penetrate 3 to 4 inches into the soil. Aerifiers with reciprocating arms are preferred because they penetrate the soil more deeply and make more holes per square foot than aerifiers pulled behind tractors. Tools that slice or spike into the soil do little to relieve compaction and are not considered aerifiers but they can help improve water infiltration.

Use the aerifier to make 20 to 40 holes per square foot of lawn. You may need to make several passes with the aerifier, in at least two different directions, to make this many holes.

Aerate your lawn only when the grass is growing (spring or fall, for cool-season grasses; in early to midsummer for warm-season lawns). The soil should be moist enough that the tines can penetrate the soil but not so wet that the soil sticks to the tines or the heavy equipment makes ruts in the lawn.

After aeration, the lawn will be covered with little columns of soil. Mow the plugs after they dry to help break them up or alternatively pull a drag of some kind across the surface to break up the plugs into smaller pieces. The plugs will break down with some moving back into the holes in a loose fashion and other soil topdressing the surface.

Thatch is a tightly intermingled organic layer of dead and living shoots, stems, and roots that accumulates just above the soil surface (Figure 17). You may first notice thatch as a “spongy” feeling when you walk across the lawn, almost like walking on a thin mattress.

A small amount of thatch is desirable because it moderates soil temperature fluctuations and improves the grass’s ability to tolerate traffic. Too much thatch interferes with water and air movement into the soil, reduces fertilizer and pesticide response, and increases disease and insect activity. If the grass roots begin to grow into the thatch, they become susceptible to cold, heat, and drought stress.

Thatch is more common in lawns that receive lots of maintenance than in lawns receiving less care. Over fertilizing and/or over watering can cause thatch. Thatch can be a problem if the soil is compacted and poorly drained. Thatch most commonly develops in lawns of zoysiagrass, strong creeping red fescue, and Kentucky bluegrass. Lawns of tall fescue and perennial ryegrass rarely develop a thatch problem.

Aerification can help reduce thatch in the lawn. You can also use a power rake (also known as a dethatching machine) to remove the thatch layer. Power rakes have blades that cut through the thatch down to the soil surface, tearing and pulling up the thatch. However, dethatching with a power rake is very destructive. Because of this, it is best to use an aerifier rather than power rake.

If the layer of thatch is more than 3/4 inch thick, you can reduce it by aerification. Aerate the lawn annually and reduce your water and fertilization rates to reduce thatch buildup.

Diagnosing Turf Damage

The effects of environmental stresses influence the health of the turf and its subsequent quality. Environmental stresses can reduce aesthetic quality through decreased uniformity, density, color, and smoothness. Further, environmental stresses can reduce function quality by reducing turf elasticity, yield, verdure, rooting, and recuperative ability.

Turf can and will decline from environmental stresses despite your best efforts to select, establish, irrigate, mow, and fertilize turf correctly. Environmental stresses can be both biotic and abiotic. Biotic stresses are those caused by living organisms and include stress or damage to turf from insects, nematodes, diseases, and weeds. Abiotic stresses are from non-living chemical or physical factors in the environment. Abiotic stresses include heat, drought, cold, salt, shade, traffic, waterlogging, and other stresses.

To help diagnose these abiotic and biotic stresses, we recommend that you scout − to inspect, observe, or survey the site in order to gain information on turf condition and pest presence.

Scouting offers many benefits:

- Identifying weeds when they are small and easy to control

- Detecting insects and diseases when populations are low in order to prevent widespread damage

- Assessing the quality and growth of the turfgrass plants

- Identifying the initial symptoms of abiotic stress before symptoms worsen and damage spreads

- Recognizing environmental factors that might be influencing turf performance or pest activity

- Evaluating the activity or success of recent cultural practices or pesticide applications.

Turf Problems

Weeds, insects, and diseases cause problems in home lawns. Thick, healthy lawns are your best defense against these pests. Healthy lawns will out-compete most pests and recover more quickly from both abiotic and biotic damage.

The lawn problems discussed below include:

- Thin lawns of cool-season grass.

- Weeds (includes information about herbicides).

- Grubs and other insects.

- Moles.

- Diseases.

Thin Cool-season Lawns

Lawns that have been neglected or have suffered from the summer’s heat and drought may be thin and need rejuvenation. You can improve many lawns simply by mowing, fertilizing, and irrigating as described earlier in this chapter.

If you decide the lawn needs more help, there are several options.

- Overseeding (applying grass seed to an already established lawn) will help improve lawn density. To overseed, apply starter fertilizer and then grass seed at the rates listed Tables 2 and 3. Aerify the area before applying to improve seed-soil contact. Alternatively, use a slit seeder to get the seed incorporated into the soil. Scattering seed on the surface without incorporating the seed somehow is rarely successful. Just as with new lawns, follow-up care is important — water, mow frequently, and fertilize as needed.

- Reseed small bare spots to fill in brown areas of an an otherwise robust lawn. Rake the soil in these areas beforehand to loosen the seedbed and after applying the seed to ensure good seed-soil contact. Next, irrigate to ensure good germination. Alternatively, lightly topdress the areas with 0.25 – 0.5 inches of loose topsoil after seeding. Bare areas four inches in diameter or smaller will often fill in without reseeding if the lawn is watered and fertilized.

- Complete lawn renovation involves killing all the vegetation in the lawn, and then seeding as you would to install a new lawn. You may choose this option if perennial grassy weeds have invaded your lawn, if you want to change the type of grass in your lawn, or if your lawn is damaged from traffic, disease, or other stresses.

- Seed the new lawn in late August or early September. Several weeks before that, begin the process of killing all the plants in the existing lawn. Use a nonselective herbicide like glyphosate. Multiple applications may be needed to kill persistent perennial weeds.

- The last step before seeding is soil preparation. If the soil is not compacted and the previous lawn had no thatch, use an aerifier or a power rake to prep the soil. If the soil is compacted, till to a depth of 4 inches and allow the soil to settle for a week or two before seeding. On lawns with considerable thatch, use a power rake and remove the thatch it pulls up.

- When you are ready to seed, apply starter fertilizer and scatter the grass seed, and then water, mow, and fertilize as described previously.

Weeds

More information about weeds and weed control (including information about herbicides) specific to landscape beds and nurseries is available in Chapter 10: Weed Control in Nursery and Landscape Plantings. This section briefly addresses weed control in turfgrass systems. For additional and advanced information, the following publication is recommended: Turfgrass Weed Control for Professionals, 128 pages, available at: https://mdc.itap.purdue.edu/item.asp?Item_Number=TURF-100.

The easiest, most efficient approach to control weeds is to address them before they get out of hand. Although you can use herbicides to control weeds, preventing weeds from becoming a problem is the better option.

Weeds are not necessarily a sign of poor lawn care. Weed seeds are present in all soils. The right environmental conditions may stimulate a weed seed to finally germinate. Perhaps aeration brings a few weed seeds to the surface or weed seeds from surrounding yards or wild areas blow into your lawn.

As a rule of thumb, there are more ways to control weeds that are different from the crop you are growing than there are ways to control weeds that are similar to your crop. For example, in this case, your “crop” is your lawn. Most lawn grasses in Indiana are perennial, cool-season grasses. If the weed is also a perennial, cool-season grass, it will be difficult to find a way to control it without also harming the lawn. If the weed is an annual grass, you may have more control options. If the weed is a broadleaf or sedge, you may have even more options.

By now you should be saying to yourself, “That means I have to identify the weed.” Yes, that is, of course, the best option. There are numerous weed books to help you identify weeds including the recommended reference above and the photos here (Figure 18).

We can use these classifications to think about weeds:

- Annual weeds vs. perennial weeds. Some weeds germinate, grow, flower, set seed, and die all within 12 months. These are annuals. The annual weeds growing on a property this year will continue to be a problem on the property next year because new weeds will grow from the seeds they produce. Crabgrass and purslane are examples of annual weeds. Perennial weeds live for several years and have underground roots and stems that survive through the winter. They may spread by seed, but many perennial weeds have stolons or rhizomes and can spread and cover large areas of your lawn. Canada thistle, dandelion, and nimblewill are examples of perennial weeds.

- Grassy weeds vs. broadleaf weeds vs. sedges. Grassy weeds look very much like your lawn grass, but they may be coarser in texture (wider leaves) or grow more quickly than your lawn grass. Otherwise, desirable grasses can be weeds, too. Zoysiagrass growing in the center of a cool-season lawn is a weed. It is brown all winter while the rest of the lawn is green. Crabgrass and quackgrass are other examples of grassy weeds. Broadleaf weeds are dicots and do not usually have long, slender leaves. They often have showy flowers. Thistles, plantains, dandelion, and ground ivy are common broadleaf weeds. Sedges have solid, triangular stems (in most species). The have leaves that extend in three directions (three-ranked). Yellow nutsedge is the most common sedge weed in lawns.

- Cool-season weeds vs. warm-season weeds. Just like lawn grasses, most plants (including weeds) have a temperature preference — some prefer to grow when it is cool, others when it is warm. These preferences are particularly relevant for annuals. Knowing when the seeds germinate (when it is cool in spring or when it is hot in summer) can help you control the weed. Some cool-season annuals are known as winter annuals. These plants germinate in fall, survive the winter, and then flower in early spring. Common chickweed and corn speedwell are cool-season winter annual broadleaf weeds. Annual bluegrass is a cool-season winter annual grass. Summer annuals germinate in the spring, grow actively during the summer, flower, set seed in late summer, and die in fall. Crabgrass is a warm-season annual grass that germinates in spring. Prostrate spurge is a warm-season summer annual broadleaf common in lawns.

Controlling Weeds Culturally

Use these tactics to culturally control turf weeds:

- Exclusion.

- Purchase weed-free mulch, manure, compost, topsoil, and straw.

- Purchase weed-free grass seed.

- Clean equipment after working in an area with lots of weeds.

- Mow regularly to cut off any weed seeds before they mature.

- Make the turf more resistant to weed invasion.

- The best defense against weeds is to care properly for the turf.

- Water, mow, and fertilize as recommended for your type of turf.

- Lawns that are not growing well, such as those on compacted soils, in shady areas, or in areas with lots of foot traffic, will often be thin and prone to weed problems.

- Aerate your lawn to relieve compaction.

- These techniques are known as cultural control of weeds.

- Remove the weeds from the property.

- Dig the weeds out when they are small (often called mechanical control).

- If weeds are persistent, consider chemical control with herbicides.

Controlling Weeds with Herbicides

There are many types of herbicides. Some herbicides kill all types of plants — these are called nonselective herbicides. Glyphosate (the active ingredient in Roundup® and other products) kills almost all plants: grasses and broadleaf plants, annuals and perennials. If you use nonselective herbicides on the weeds in your lawn, you may kill the weeds but you will also kill some of the grass.

Some herbicides kill only certain types of plants — for example, broadleaves but not grass plants. These are the selective herbicides. You may be able to use some of these selective herbicides to control broadleaf weeds without killing the lawn grass.

Preemergence herbicides kill very small plants, just as they are emerging from their seeds. Preemergence herbicides are used to keep new weeds from growing. Once the seedling has emerged from the soil, preemergence herbicides have no effect. To kill weed seedlings and larger plants, you will need to use postemergence herbicides.

If you choose to use an herbicide, evaluate the situation before you treat. You may be able to spot-treat just the weeds instead of your whole lawn. Make sure to read and follow herbicide label instructions.

Information about using herbicides to control the most common lawn weeds is given on the next few pages. Remember, you can control many weed problems without chemicals if you are willing to put in the time and energy to maintain a healthy lawn and hand weed when necessary.

Perennial Broadleaf Weed Control

To control perennial broadleaf weeds already growing in your lawn, use a postemergence herbicide that is specific for broadleaf plants and does not harm grasses (Table 8). Postemergence herbicides applied as liquids are more effective at controlling these weeds than granular products. Read product label instructions before applying. Liquid herbicides are usually applied to dry grass. Granular postemergence herbicides are applied to damp grass so they dissolve quickly.

Applying broadleaf herbicides in fall (mid-September to early November) is most effective and less likely to damage other plants in your yard. The herbicide is moved to the roots of the weeds along with winter food reserves as the plant is going dormant, efficiently killing the plant.

A late spring or early summer application after the weed has flowered can also be effective. For some weeds, you may see the tops die but the plant will recover later.

Remember, many of the plants in your garden — trees, shrubs, vegetables, and ornamental annuals and perennials — are also broadleaf plants, and herbicides can damage them. Damage is more likely to occur when the plant is growing in late spring and early summer. Fall applications of broadleaf herbicides are less likely to injure ornamental plants and kill weeds more effectively, too.

When using postemergence herbicides to kill broadleaf weeds in your lawn, follow these precautions:

- Do not apply when soil moisture is low.

- Apply on a clear, calm day when temperatures are between 50°F and 85°F.

- If you apply herbicide in a liquid form, apply just enough to wet the leaves but not so much that the herbicide drips off the leaves.

- Pay attention to rain. Rain within 24 hours of application can wash the herbicide off the leaves.

- Do not apply herbicides to newly seeded grass until you have mowed three times.

- Wait four to six weeks after laying sod before applying any herbicides.

- Apply herbicides as specified on the label. Pay attention to application timing, application site, interval between applications, interval before and after seeding, and so on.

- Apply a product only to the turfgrass species listed on the label.