Disclaimer and Disclosures: This is an informational resources page/guide and should NOT be used in lieu of training. We hope in this difficult time it will act as a general guide, but specifics of implementation depend on several and complex factors that cannot be fully considered in this format. Click here to see Dr. Malandraki's disclosures.

To cite this page:

Malandraki, G.A. (2020, April 24). Telehealth Recommendations for Dysphagia Management during COVID-19. Purdue I-EaT Lab. https://www.purdue.edu/i-eatlab/telehealth-resources-for-dysphagia-management-during-covid-19/

Demo videos coming soon!

Part C Introduction

The urgency and desire to serve patients during this critical time is understandable, however if the use of audiovisual technology and telehealth is part of the equation, specific evidence-based steps need to be followed to ensure appropriate and ethical patient care. In Part C of this guide, we include some recommended steps based on the literature, current policies, and our experiences, that may help clinicians navigate this process with integrity and safety. However, in each facility one should engage with their director of services, the legal counsel/risk management team, IT personnel, and the medical team to determine what may work best for their facility and patients. Finally, it is highly advisable that one reviews Parts A and B of this resource guide first, as well as the ASHA Telepractice Portal, and the open access American Telemedicine Association’s Principles for Delivering Telerehabilitation Services (Richmond et al., 2017) before delving into Part C.

C. Conclusion

A. Pre-requisite considerations

Before getting started, we need to emphasize critical pre-requisite considerations.

1. Candidacy - Patient, Clinician, and Procedure

Patients – Is telehealth the right model for everyone?

Despite our best intentions to treat as many patients as possible via telehealth at this time, it is important to remember that telehealth may not be the right model of service delivery for all patients. First of all, some patients may not have the resources (e.g., technology) needed, the facilitators/support personnel to help during the sessions, or may just not be comfortable with this modality (Gough et al., 2015; Turvey et al., 2013). Therefore, patient candidacy criteria need to be very carefully examined. As highlighted by ASHA, candidacy needs to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis for all types of telepractice services, including services for dysphagia (ASHA, n.d.). Table 3 offers a list of general and dysphagia-specific patient candidacy criteria that need to be carefully considered for each patient. Ultimately the decision for candidacy needs to be a medical team decision with the patient/family in the center of this decision process.

| Table 3: Patient Candidacy and Considerations | |

| General telehealth patient candidacy criteria with application to patients with dysphagia (primary sources: ASHA Telepractice Portal, n.d; Duffy, Werven, & Aronson, 1997; Gough et al., 2015; Turvey et al., 2013) | Additional criteria - specific to patients with dysphagia and their environment (primary sources: Malandraki et al., 2011; Ward, Sharma, Burns, Theodoros, Russell, 2012b) |

|

|

Clinicians – What attributes do they need to possess to be effective telepracticioners?

In addition to patient candidacy, we also need to consider clinician’s attributes. There are many attributes that we could discuss, but perhaps the most important include communication style, comfort with technology, and adaptability/flexibility (Charness, Demiris, & Krupinski, 2011; McConnochie, 2019; Miller, 2003). For in-person encounters we frequently refer to “bedside manner” and how important it is for effective clinical care. The virtual equivalent of “bedside manner” is known as digital bedside manner (or at times referred to as website manner), that is, the way we interact with the patient through technology. As we all know, in addition to choice of words and to the tone of our voice, our body language is also an integral part of these interactions (Charness et al., 2011; Heath & Nicholls, 1986). However, nonverbal communication can be significantly limited by technology. Therefore adjustments in our communication style may be essential and require being comfortable with technology, and adaptability/flexibility. For example, simple things like looking straight at the camera will ensure a feeling of real eye contact for the patients. Or using head nodding, maybe more so than we do during an in-person encounter, will communicate to the patient that we are truly listening. For a plethora of communication tips on digital bedside manner, see articles in the following blogs (https://www.wheel.com/blog/ways-to-improve-your-telehealth-webside-manner/), (https://telemedicine.arizona.edu/blog/bedside-manners-telehealth-understanding-how-your-screenside-manners-matter), (http://www.telemedmag.com/article/improving-digital-bedside-manner/).

In a survey of 67 SLPs that explored clinical and technical insights into telepractice methods, the respondents indicated that many additional domains needed to be adjusted for effective telepractice delivery (Grillo, 2017). The main components included technology, therapy materials, cueing/modeling techniques, interaction with facilitators, and the environment. According to the ATA Principles for Telerehabilitation Services, clinicians shall be willing to modify intervention materials, techniques, equipment, and/or the physical setting in order to meet telepractice delivery standards (Richmond et al., 2017). Therefore, adaptability and motivation to adjust to this new service delivery model are also necessary clinical attributes.

Evaluation and Treatment Procedures – What procedures are evidence-based? A MUST READ!

Another crucial topic to consider is what specific dysphagia tele-management procedures have been found, through research, to be feasible, valid, and reliable. A growing body of literature has investigated the reliability and clinical utility of the tele-management of dysphagia (for reviews see, Burns & Wall, 2017; Malandraki & Kantarcigil, 2017; and Ward & Burns, 2014). The studies reviewed in these papers have clearly demonstrated that swallow assessments (both clinical and VFSS) conducted via telehealth  are safe, valid and reliable when compared to traditional in-person evaluation methods (e.g., Burns et al., 2016; Malandraki et al., 2011; Malandraki et al., 2013; Kantarcigil, Sheppard, Gordon, Friel, & Malandraki, 2016; Morrell et al., 2017; Perlman & Witthawaskul, 2002; Raatz et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2011; Ward et al., 2012a; Ward et al., 2013). Emerging evidence for the use of telehealth for dysphagia treatment has also surfaced (e.g., Burns et al., 2017; Malandraki et al., 2014), with the first multi-site clinical trial of head and neck cancer patients reporting favorable service efficiency, cost savings, and clinician and patient satisfaction outcomes for the telehealth arm of the study (Burns et al., 2017). Therefore, at this time, there are varying degrees of positive research evidence for three types of procedures: tele-clinical swallowing assessments, tele-VFSS, and tele-treatment sessions. However, it needs to be emphasized that in all of these published studies, the investigators followed specific and strict procedural, training, and practical guidelines. Therefore, all the positive outcomes reported are specific to the methodologies used in these studies. This is critical to understand, as deviations from these protocols and methodologies may NOT yield similarly positive and safe results. Evidence-based practice indicates that our evaluation and therapeutic approaches should be supported by high-quality research evidence. When research evidence is not available, clinicians should use their professional judgment, experience, and expertise in making the best possible decisions for their patients.

are safe, valid and reliable when compared to traditional in-person evaluation methods (e.g., Burns et al., 2016; Malandraki et al., 2011; Malandraki et al., 2013; Kantarcigil, Sheppard, Gordon, Friel, & Malandraki, 2016; Morrell et al., 2017; Perlman & Witthawaskul, 2002; Raatz et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2011; Ward et al., 2012a; Ward et al., 2013). Emerging evidence for the use of telehealth for dysphagia treatment has also surfaced (e.g., Burns et al., 2017; Malandraki et al., 2014), with the first multi-site clinical trial of head and neck cancer patients reporting favorable service efficiency, cost savings, and clinician and patient satisfaction outcomes for the telehealth arm of the study (Burns et al., 2017). Therefore, at this time, there are varying degrees of positive research evidence for three types of procedures: tele-clinical swallowing assessments, tele-VFSS, and tele-treatment sessions. However, it needs to be emphasized that in all of these published studies, the investigators followed specific and strict procedural, training, and practical guidelines. Therefore, all the positive outcomes reported are specific to the methodologies used in these studies. This is critical to understand, as deviations from these protocols and methodologies may NOT yield similarly positive and safe results. Evidence-based practice indicates that our evaluation and therapeutic approaches should be supported by high-quality research evidence. When research evidence is not available, clinicians should use their professional judgment, experience, and expertise in making the best possible decisions for their patients.

2. Secure access to network/platform/server for storage and documentation

In addition to candidacy, another consideration prior to implementation, includes ensuring secure access to the network or platform one decides to use. Even if a secure telehealth platform is utilized, especially if clinicians are offering services from home, access to that platform needs to also be secure. Here is a bit more information on this topic for different settings and scenarios.

Within Hospital Connection or Clinic-to-Home Connection: If you are providing tele-sessions within a hospital (e.g., from clinician’soffice to a patient room) or from a clinic to a patient’s home, the hospital/clinic should be already using a secure network, password protected devices (laptops or iPads), and they should have a secure and HIPAA aligned setup in place. If you are unsure, communicate with your facility’s IT and legal/risk management team to ensure the connection and the whole setup is secure.

Home-to-Home Connection: During this time many clinicians may be working from home and may even be using personal computers/tablets to connect with their patients.  Although this is not generally advised, we are experiencing an unprecedented situation. In those situations, a Virtual Private Network (VPN) or a similar secure setup will be important. Clinicians ideally should be connecting to their employers secure network using VPN and/or through a two-point authentication service, and conduct their sessions through that network. Connecting through a personal network (e.g., the Wi-Fi you have at home for personal use) is NOT advisable for practical, legal, and security reasons. Further, another important consideration involves the server that will host any saved data, including the server used for documentation. These servers will also need to be secure to ensure any saved data are protected and that data can be reviewed or audited at a later time (Gough et al., 2015).

Although this is not generally advised, we are experiencing an unprecedented situation. In those situations, a Virtual Private Network (VPN) or a similar secure setup will be important. Clinicians ideally should be connecting to their employers secure network using VPN and/or through a two-point authentication service, and conduct their sessions through that network. Connecting through a personal network (e.g., the Wi-Fi you have at home for personal use) is NOT advisable for practical, legal, and security reasons. Further, another important consideration involves the server that will host any saved data, including the server used for documentation. These servers will also need to be secure to ensure any saved data are protected and that data can be reviewed or audited at a later time (Gough et al., 2015).

3. Obtaining signatures online

Another frequently asked question is what is the best way to obtain signatures online. To obtain legal signatures online, for example for your consent form or any other sort of agreements you/your facility require the patient to sign, services such as DocuSign, Adobe Pro with E-sign, or PactSafe (and several others) can be used. If an online secure service is not an option due to cost, and the patient has a scanner, that can be another way to get your forms signed and returned to you, if approved by your legal team. If it is not possible to have a document signed online or via a scanned document, using regular mail can also be used. Choosing a specific service or method to obtain legal documents’ signature needs to be approved by your legal counsel/risk management team.

Alternative methods (ONLY if approved using legal/risk management advice) could be:

- Sending pdfs of your consent forms/agreements to the patient and asking the patients/family to email you with a typed statement acknowledging and agreeing to all terms. In some states, an exchange of emails (chain of emails) can form a legally binding contract, but you need to double check with legal counsel about your state and situation.

- Sending pdfs of your consent forms/agreements to the patient and asking the patients/family to verbally consent during your first session and video record their verbal agreement. Similarly, please check with legal counsel before using this process.

B. Recommendations to ensure feasibility, safety, and validity

Important introductory reminders

As we now start the discussion about implementation, it is imperative to highlight once more that we will NOT be able to provide services via telehealth to ALL patients during this time. For those who are potential candidates for tele-services, we still need to consider how feasible, safe, and valid this service delivery model is on a case-by-case basis (ASHA Telepractice Portal, n.d.). We also need to consider if we have the appropriate and evidence-based technological and practical setup at both the clinician and the patient ends, and all the legal and clinical regulations in place to offer our services via telehealth in an equivalent way (ATA, 2014). As a reminder, telehealth services should be equivalent or not inferior to in-person services. If for any reason, we believe or have evidence that the services we provide via telehealth are not equivalent or are inferior to the services we would be able to provide in-person, then the services are not appropriate and should cease.

1. Initial implementation steps

Initial Step 1: Case history and other forms - Making your forms online forms

Completing case history, evaluation, quality of life, or other forms is often an initial component of a swallowing evaluation session. Therefore, one consideration is to transform these forms into online forms, so that patients and families can easily access them and complete them. However, there are some caveats to consider. First, for most published standardized and validated forms/tests, special permission needs to be requested by the publishers and developers of the tests. For any forms that the clinician/facility has developed themselves, creating electronic versions that can be completed online is not trivial. In one of our prior studies, we developed an electronic case History Tool/form (known as e-HiT) for adult dysphagia seen in the figure below and compared its effectiveness with a paper-based version on completion time, completeness, independence, and patient  perceptions/satisfaction in a randomized controlled trial including 40 adult outpatients with basic computer literacy skills (Kantarcigil & Malandraki, 2017). Our results showed that the forms were comparable in most variables examined, with higher satisfaction reported for the electronic form (Kantarcigil & Malandraki, 2017), showing that online completion of case history forms can be an effective alternative to in-person completion.

perceptions/satisfaction in a randomized controlled trial including 40 adult outpatients with basic computer literacy skills (Kantarcigil & Malandraki, 2017). Our results showed that the forms were comparable in most variables examined, with higher satisfaction reported for the electronic form (Kantarcigil & Malandraki, 2017), showing that online completion of case history forms can be an effective alternative to in-person completion.

The second consideration is to ensure that these online forms can be completed and transmitted to the clinician in a secure and safe way. In most facilities, case history and relevant forms can be incorporated within the EMR system and can be securely completed and transmitted to the clinician through that system. Some telehealth platforms may allow for such forms to be incorporated into the platform as well, therefore also allowing for secure completion and transmission of data. If that is not possible, secure servers and services such as RedCap can be used (Kantarcigil & Malandraki, 2017), as long as the facility has approved their usage. If the patient has signed an agreement/consent (approved by the risk management team) agreeing to exchange of information via email, a final (less secure) option includes using fillable pdf documents that can be completed online and send back to the clinician’s professional email.

For forms that may need to be completed by the patient and the clinician together (e.g., case history, or cognitive screenings) and for which cyber usage has been approved, but are not yet available online, using a document camera and screen sharing the form is a viable option (Figure 1). Many clinicians are now using document camera apps on their phones or tablets that allow them to directly share documents through specific tele-conferencing platforms.

Initial Step 2: Training/instructions for patient and/or caregiver/facilitator

For dysphagia tele-management, the use of trained facilitators/support personnel/caregivers has been extensively shown to be an important component of telehealth assessments and treatments (e.g., Burns et al., 2017; Malandraki et al., 2011; Malandraki et al., 2014; Raatz et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2012; Ward et al., 2013). Therefore, at this time given the currently available evidence, use of trained facilitators for dysphagia tele-management is highly advised. For optimal training, clinicians need to take the time and create  customized step-by-step instructions regarding technology use, and practical and safety guidelines for facilitation. These instructions have to be specific to the system and to the evaluation or treatment procedure used, and provide easy to understand instructions, as well as troubleshooting ideas. In addition, trained facilitators/caregivers for dysphagia telehealth services can be critical in assisting patients with feeding, modifying the environment or the stimuli (e.g., changing the camera angle/view or the food item being tested), repeating directions, and more importantly intervening to address any potential safety issues (e.g., Burns & Wall, 2017; Malandraki et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2012).

customized step-by-step instructions regarding technology use, and practical and safety guidelines for facilitation. These instructions have to be specific to the system and to the evaluation or treatment procedure used, and provide easy to understand instructions, as well as troubleshooting ideas. In addition, trained facilitators/caregivers for dysphagia telehealth services can be critical in assisting patients with feeding, modifying the environment or the stimuli (e.g., changing the camera angle/view or the food item being tested), repeating directions, and more importantly intervening to address any potential safety issues (e.g., Burns & Wall, 2017; Malandraki et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2012).

Published studies have successfully used trained nursing staff and SLP aids for tele-clinical swallowing assessments, and, parents/caregivers for tele-evaluation and tele-treatment sessions for adult and a small number of pediatric patients with dysphagia (Burns et al., 2017; Malandraki et al., 2011; Malandraki et al., 2014; Raatz et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2012). In most of these studies considerable time was spent – before the initiation of the procedure or treatment – to train the facilitators on the specific procedures with which they would be helping. This is an important parameter to remember. Our typical training guides for facilitators are centered on the following six main topics:

- Detailed step-by-step instructions on how to connect with the clinician. This will be dependent on the specific telehealth system and platform one uses.

- Detailed step-by-step instructions on how to prepare for the session in the home or the remote setting. This may include preparing the environment (e.g., lighting, closing the curtains, positioning the chair), collecting items needed for the session (e.g., clear cups and spoons), and testing the connection etc.

- Detailed and clear instructions on how they are to facilitate the session. For example, if they will be helping during the cranial nerve assessment, listing the main components they will need to help with will be important (e.g., providing tasting stimuli to patients; helping with strength related assessments etc.).

- Clear instructions/rules about when the facilitator may intervene and override the remote clinician, for example in the case of a choking event or connection interruptions.

- Technical assistance ideas and clinician and tech support contact information in cases of technical disruptions and difficulties.

- Clear delineation of the emergency plan (e.g., who will call 911 in case of an emergency; contact information of local emergency services).

Here is a sample form we have used in our research clinic. This sample is provided ONLY for illustration purposes.

Initial Step 3: Reminders for Plan B and Emergency Plan

This step is less of a concern in acute care where emergency plans are already typically in place, but it is a must for outpatient clinics and home health. Although the Plan B and the Emergency Plan should be already outlined in the consent form, it is best practice to remind the patient/family and the facilitator these plans in the beginning of each session (Gough et al., 2015; Turvey et al., 2013).

2. For implementation

1. Technology - Main and Peripheral Systems

Software/Hardware

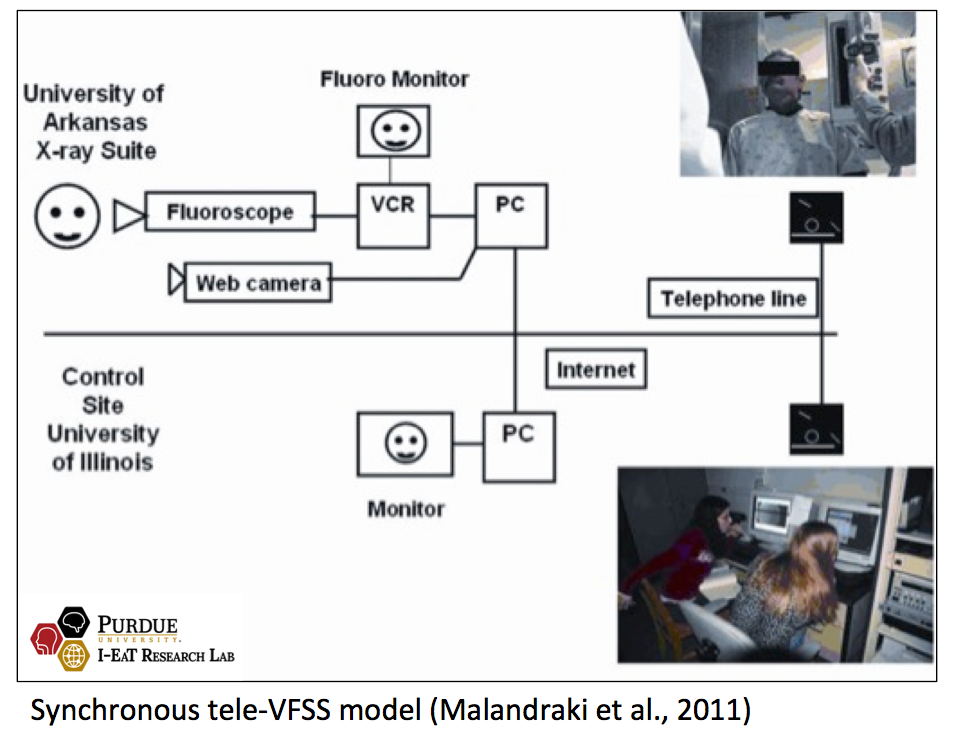

As mentioned earlier, synchronous methodologies have been extensively used to deliver services for patients with dysphagia in several research studies with highly positive outcomes (e.g., Burns et al., 2016; Burns et al., 2017; Malandraki et al., 2011; Malandraki et al., 2014; Morrell et al, 2017; Perlman, & Witthawaskul, 2002; Raatz et al., 2019; Ward et al., 2012a; Ward et al., 2013). As an important reminder, these positive outcomes are specific to the methodologies used in these studies.

To implement synchronous clinical tele-assessments and tele-therapy sessions live video-conferencing is needed. That means that both the clinician and the patient need to have access to a computer or laptop (or tablet – though not optimal), and to a software platform that allows live secure interaction. Ideally, technology considerations should be determined with the guidance/help of someone with expertise/experience in IT and telehealth knowledge. Under the current condition, that may not always be possible, but at least IT support should be available in most sites or even from a distance.

In dysphagia telehealth research, both dedicated (business class) technology solutions, and more widespread (software based) technology solutions have been used with success, although varying degrees of image and audio quality and connectivity issues have been reported at times (e.g., Malandraki et al. 2011; Ward et al., 2013).

As mentioned in Part B of this guide, there is an abundance of commercial videoconferencing hardware and software available. Clinicians need to remember that privacy, security, authentication, and even reimbursement considerations need to be carefully reviewed before deciding on a specific videoconferencing platform. See Part B of this guide and the additional resources page for a list of several available platforms with HIPAA aligned versions.

For dysphagia-specific telehealth technology solutions, clinicians are encouraged to also consider the following characteristics:

- Large enough screen to allow full view of patient and clinician at the same time, and possibly additional camera views or materials to be shared (e.g., Burns et al., 2016; Malandraki et al., 2014) . Alternatively, the use of two screens (on the clinician’s end) can also be beneficial.

- Ability of the software platform to allow screen share, so that clinicians can share instructions, stimuli and reinforcements/rewards (e.g., Malandraki et al., 2014). Most platforms have this feature.

- Ideally the use of an external web camera on the patient's site. This will allow to move the camera closer to the patient more easily for clearer views.

- Ability of the platform to allow simultaneous video/audio and chat/text, so that patients who may not be able to verbalize can text their responses into the chat box of the platform. Most platforms have this feature.

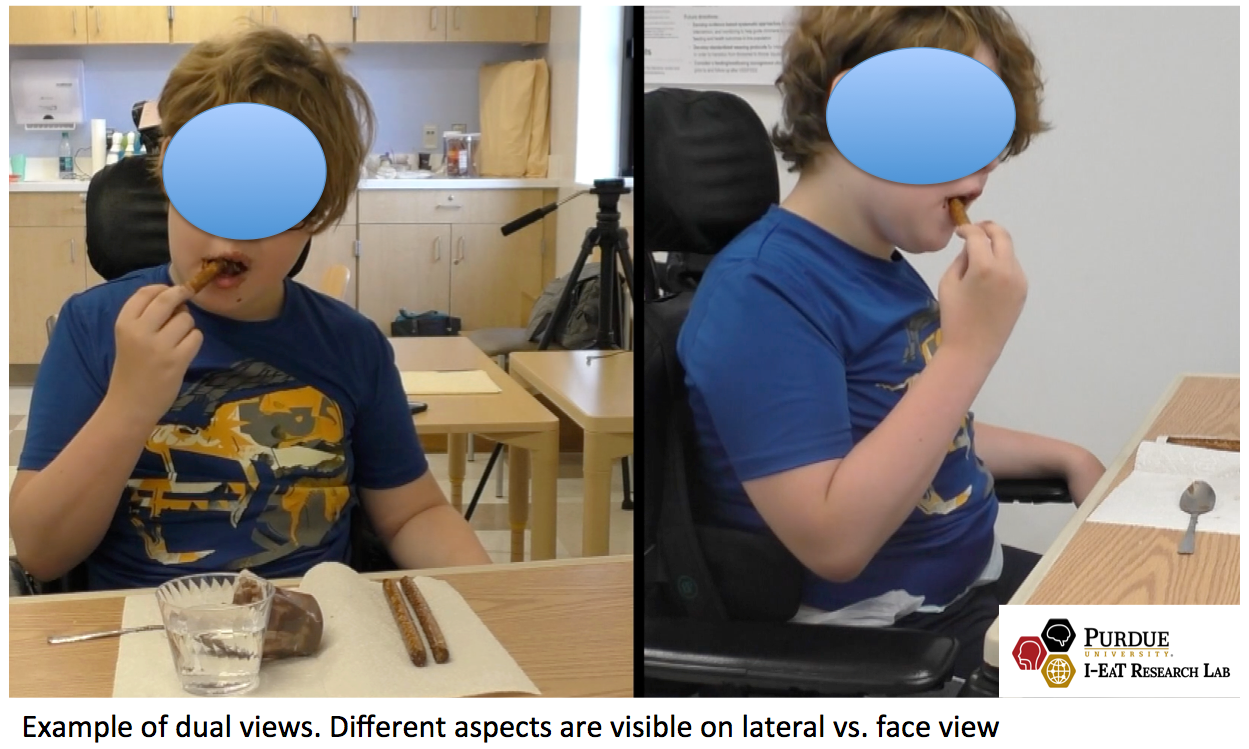

- Ability of the platform to allow two cameras (from patients’ room) to be connected at once, so clinicians can visualize multiple views of the patient’s seating and head, neck and torso (for example, front view and lateral view) as seen in the figure below. Additional peripheral or hardware devices may be needed for this function to be optimal (see Peripheral devices section).

- Ability to control who enters the tele-session and ability to mute and start/stop cameras on both ends for security and confidentiality purposes (Gough et al., 2015). Most platforms have this feature.

- Ability of the platform to modify the relative size of each image shared with the patient, to increase flexibility on how stimuli are presented. Several platforms allow this feature.

In addition to synchronous methods and live interaction, asynchronous applications can also be valuable especially in the current situation and with the high definition video recording capabilities that most phones and iPads have.  For example, asking a parent to videotape a child consuming their typical meal or snack (Clark et al., 2019; Kantarcigil et al., 2016), or taking a picture of the seating of a child before the evaluation is conducted and sending the picture to the clinician (Raatz et al., 2019) could offer valuable information for clinical assessments. Considerations about how this information will be shared with the clinician in a secure and confidential way need to be discussed and agreed upon beforehand. Also, we recognize that in the US billing and reimbursement regulations may limit the use of asynchronous telehealth for dysphagia management at this time, therefore clinicians need to check with their providers before adopting any of these models.

For example, asking a parent to videotape a child consuming their typical meal or snack (Clark et al., 2019; Kantarcigil et al., 2016), or taking a picture of the seating of a child before the evaluation is conducted and sending the picture to the clinician (Raatz et al., 2019) could offer valuable information for clinical assessments. Considerations about how this information will be shared with the clinician in a secure and confidential way need to be discussed and agreed upon beforehand. Also, we recognize that in the US billing and reimbursement regulations may limit the use of asynchronous telehealth for dysphagia management at this time, therefore clinicians need to check with their providers before adopting any of these models.

The development of apps and devices that provide the ability of patients to practice their prescribed exercises at home while data are transmitted remotely to clinicians have started to emerge as well, both in research (e.g., Constantinescu et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2019; Starmer et al., 2018; Wall et al., 2017; Wall et al., 2020), and in the commercial domain (e.g., use of the Iowa Oral Performance Instrument, Tongueometer and others). One may not realize this, but all these are also examples of asynchronous tele-services for dysphagia.

Quick notes about tele-instrumental assessments: Although the discussion for the use of tele-instrumental assessments has been limited at the present time, there is research evidence showing that tele-VFSS assessments can be as reliable and valid as in-person VFSS assessments (Burns et al., 2016; Malandraki et al., 2011). However, in these studies the equipment, training of clinicians and facilitators, and all safety requirements were first put in place and standardized protocols were used. This is also important to remember. For optimal clinical outcomes, training and standardization are essential to our clinical practices.

In addition, to conduct tele-VFSS assessments, critical and expensive  hardware and peripheral devices would be needed. Burns and colleagues used a commercially available system (C20 Cisco TelePresence) in their study and reported good image quality, however the remote clinician was in the same facility as the patient, and not in a different building (Burns et al., 2016). In addition, high-end peripheral equipment (high definition cameras and microphones) would also be critical, so that both the remote clinician and the patient can view each other and interact in real-time. Although a few studies on tele-laryngoscopy have been published (e.g., Dorrian et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2000; Wildi et al., 2004), to our knowledge no studies have explored the use of telehealth in performing FEES.

hardware and peripheral devices would be needed. Burns and colleagues used a commercially available system (C20 Cisco TelePresence) in their study and reported good image quality, however the remote clinician was in the same facility as the patient, and not in a different building (Burns et al., 2016). In addition, high-end peripheral equipment (high definition cameras and microphones) would also be critical, so that both the remote clinician and the patient can view each other and interact in real-time. Although a few studies on tele-laryngoscopy have been published (e.g., Dorrian et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2000; Wildi et al., 2004), to our knowledge no studies have explored the use of telehealth in performing FEES.

In addition to these synchronous telefluoroscopic models, asynchronous VFSS teleconsultation models can also be valuable. In a study where a newly trained clinician completed VFSSs of patients with dysphagia, and the videos were then uploaded on a secure server for independent review by a dysphagia expert, results showed good agreement between the two clinicians for most diagnostic parameters (Malandraki et al., 2013). Importantly, substantial disagreements on treatment recommendations were observed for approximately 50% of the sample, suggesting that without the expert tele-consultation, quality of care would have been substandard for these patients (Malandraki et al., 2013). This study demonstrated the additional and critical value of telehealth for teleconsultation services for dysphagia.

Internet Connectivity – Bandwidth

Having a solid Internet connection is critical in being able to offer quality telehealth for any type of services, and even more so for swallowing tele-evaluation and tele-rehabilitation services. A solid connection allows for good quality transmission of video and audio data. This is often referred to as bandwidth, that is, the data rate supported by a network connection. Bandwidth needs to be considered at both the clinician’s and the patient’s end.

In dysphagia telehealth research successful sessions have been conducted with relatively low bandwidth levels (ranging from as low as 128 Kbps and as high as 1Gbps). However, in some of these studies, issues with video or audio quality and connectivity were reported (e.g., Malandraki et al., 2011; Ward et al., 2013), therefore the use of higher bandwidth has been suggested whenever possible (Ward & Burns, 2014). According to ATA guidelines, bandwidth should be at a minimum of 384 Kbps for both upload and download, and should provide a minimum of 640 x 360 resolution at 30 frames/second (ATA, 2014; Gough et al., 2015). In general, the higher the bandwidth on both ends, the better the connection will be.

For the US, according to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), there are specific recommendations for minimum bandwidth speeds for different facilities and telehealth needs. The FCC website reports the recommended FCC minimum bandwidth speeds for each type of facility: https://www.healthit.gov/faq/what-recommended-bandwidth-different-types-health-care-providers

Also, it has to be noted that many cloud-based videoconferencing telehealth platforms (such as Zoom and Cisco Webex) can function adequately even on a modest bandwidth of 1.5Mbps (Baird Struminger & Arora, 2019). However, if multiple users are connected to the same network, then additional bandwidth will be required to ensure video and audio transmission is uninterrupted. To test the bandwidth of both the clinician and the patient connections, a plethora of sites provide this information freely and easily. If a patient does not have a strong Internet connection, asking them to switch to a wired dedicated line may improve their Internet connectivity (Gough et al., 2015). Patients and clinicians can also purchase a wireless extender or booster to troubleshoot and improve bandwidth issues.

Peripheral Devices

With adequate funding and time to build a telehealth solution, acquiring high definition web cameras and high-quality microphones would be critical considerations (ATA, 2014). For example,  web cameras with pan/tilt/zoom (PTZ) capabilities and far end controls that can be controlled remotely by the clinician are highly valuable, because they allow the clinician to scan the entire room where the patient is, and tilt and zoom to specific body areas that need to be evaluated or seen more extensively (e.g., Burns et al., 2017; Malandraki et al., 2011; Ward et al. 2009). In addition to PTZ cameras, the use of two cameras that offer both lateral and frontal views of the patient’s face when trial swallows are attempted can also be extremely helpful (Kantarcigil et al., 2016) as seen in the figure to the right. Similarly, there are important considerations with respect to microphone selection. Ideally we want to consider echo cancelling field microphones (e.g., Burns et al., 2017), a lapel microphone that enables subtle signs of difficulty (such as throat clearing) to be perceived (Ward et al., 2014), as well as the microphone response sensitivity for adult or pediatric speech signals and noise-cancellation headphones for best acoustic delivery.

web cameras with pan/tilt/zoom (PTZ) capabilities and far end controls that can be controlled remotely by the clinician are highly valuable, because they allow the clinician to scan the entire room where the patient is, and tilt and zoom to specific body areas that need to be evaluated or seen more extensively (e.g., Burns et al., 2017; Malandraki et al., 2011; Ward et al. 2009). In addition to PTZ cameras, the use of two cameras that offer both lateral and frontal views of the patient’s face when trial swallows are attempted can also be extremely helpful (Kantarcigil et al., 2016) as seen in the figure to the right. Similarly, there are important considerations with respect to microphone selection. Ideally we want to consider echo cancelling field microphones (e.g., Burns et al., 2017), a lapel microphone that enables subtle signs of difficulty (such as throat clearing) to be perceived (Ward et al., 2014), as well as the microphone response sensitivity for adult or pediatric speech signals and noise-cancellation headphones for best acoustic delivery.

Under the current condition, we may have to get by with the cameras and microphones that most computers and phones have at least at the end user (patient’s) end. Although that is not ideal, most new computers, tablets and phones have high definition cameras and adequate quality of microphones. Below are some tips to ensure the currently available peripheral devices (cameras, microphones, headphones) provide adequate input for dysphagia care:

- Placement of the cameras and/or placement of the patient will be of most importance depending on what part of the body you want to visualize or what task you want to observe. This is a task for which the facilitator will be integral.

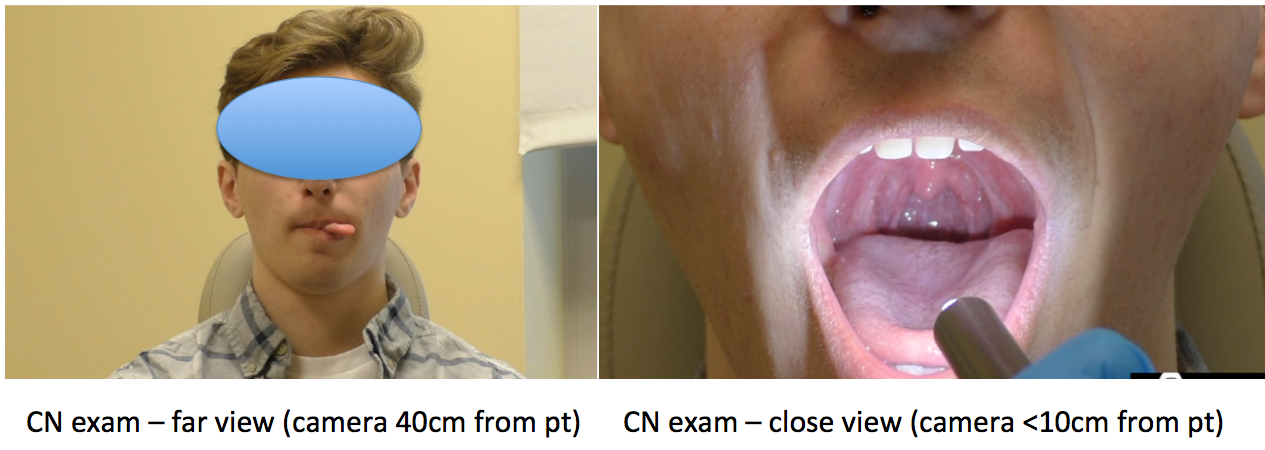

- For example, when examining most cranial nerve functions having the camera in the front/face view and relatively close to the face will likely be optimal.

Also, asking the facilitator to use a cell phone light source (or a flashlight) will enable visualization of the oral cavity and the oropharynx. Examples of both views can be seen in the figure on the right. (Video coming soon!)

Also, asking the facilitator to use a cell phone light source (or a flashlight) will enable visualization of the oral cavity and the oropharynx. Examples of both views can be seen in the figure on the right. (Video coming soon!) - When examining trial swallows, having the patient sit laterally and placing a colored tape on the thyroid notch (e.g., Malandraki et al., 2014; Ward et al., 2014) will allow for easier visualization of the swallows (Video coming soon!). If simultaneous lateral and front views of the patient’s head and neck and torso are not possible, some feeding trials or swallows should be viewed in the front view and some in the lateral view as different aspects/skills of the eating/swallowing process can be judged in each of these views.

- For example, when examining most cranial nerve functions having the camera in the front/face view and relatively close to the face will likely be optimal.

- For patients/families who own smart phones, using asynchronous methods and instructing the facilitator to record small video clips of the patient performing tasks that are difficult to visualize using a regular computer camera (e.g., velar movement during phonation) may be necessary. (Video coming soon!)

- If the patient or facility has two usb-enabled cameras, using a video usb mixer can allow for two cameras to be connected to the same platform at once. This has an additional cost, but can be very helpful. An alternative to achieve this dual view could be to connect to the call/tele-session from two computers (or a computer and a tablet), and focus each device’s camera on a different patient view. Security and confidentiality issues will need to be considered here as well.

- Peripheral digital usb-enabled devices, such as pulse oximeters, ECGs, ultrasounds that can directly connect to a computer and provide remote signals are commercially available, however they are highly expensive and their use as adjunctive tools in dysphagia assessment and treatment has been debated, is still under investigation, or requires extensive training. Several commercial companies offer what are known as telemedicine kits, including some of these peripheral usb-enabled devices. Regular pulse oximeters have been used to enhance the information the clinician receives during a clinical assessment and are more readily available (Ward et al., 2014).

2. Some considerations about the telehealth environment

Considering the environment where telehealth services are provided is another very important consideration. Krupinski, a leader in telemedicine research, has published a thorough guide on how to design telehealth work environments and those interested are highly encouraged to read that source (Krupinski, 2014). Briefly, it is important to consider both the environment at the clinician’s end and at the patient’s end. Most published teleheath studies in the area of dysphagia have been conducted in highly controlled environments in regards to both the patient site and the clinician site (e.g., Burns et al., 2017; Malandraki et al., 2011; Ward et al., 2014), i.e., clinic offices, dedicated telehealth rooms, or hospital rooms. Few have examined feasibility and reliability when the patient is at the home or school/camp setting and the clinician is at the clinic (e.g., Clark et al., 2019; Kantarcigil et al., 2016; Malandraki et al,. 2014; Raatz et al., 2019), and to our knowledge, no studies have examined the feasibility, safety, and reliability of swallowing tele-services provided when the clinician is at home. Therefore, clinicians that are delivering services from the home setting need to be extra careful and use their best clinical judgment when doing so.

It is understandable that during this challenging time clinicians may not be able to fully control the environment of the patient. However, they should make every effort to ensure the environment used is as conducive to providing clinical services as possible, with all safeguards discussed earlier in place. For example, we need to make sure that both the patient and the clinician are in comfortable and quiet rooms, free of clutter and distractions (ATA, 2014; Krupinski, 2014). Also, both should be in fully private rooms for increased privacy and security (Turvey et al., 2013). For optimal image quality, the room lights should be adjusted to ensure that shadows are minimized and windows should be closed to further enhance image quality. Further, the computer or camera should be facing a wall and not a window (Krupinski, 2014). For elderly patients light levels may need to be higher than for younger patients, as higher levels will facilitate color perception (Krupinski, 2014). Finally, clinicians should avoid wearing clothes with busy patterns, as these can be distracting and affect the image quality.

3. Specific tools and tips for clinical swallowing tele-assessments

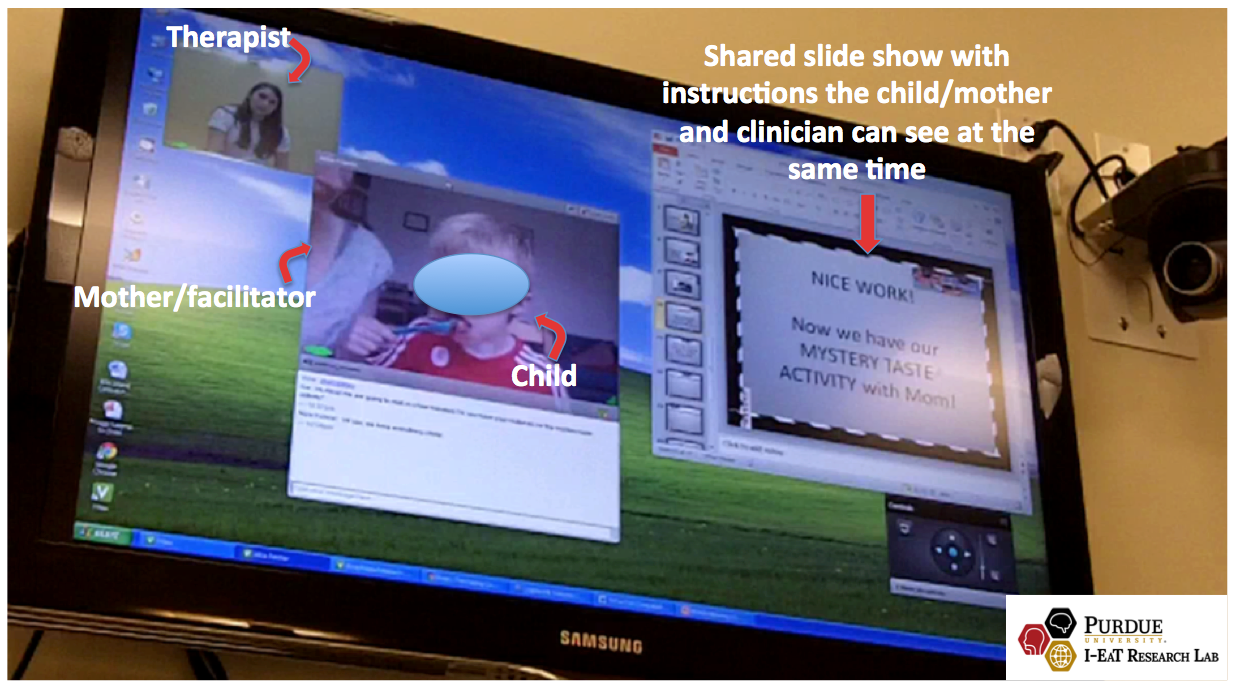

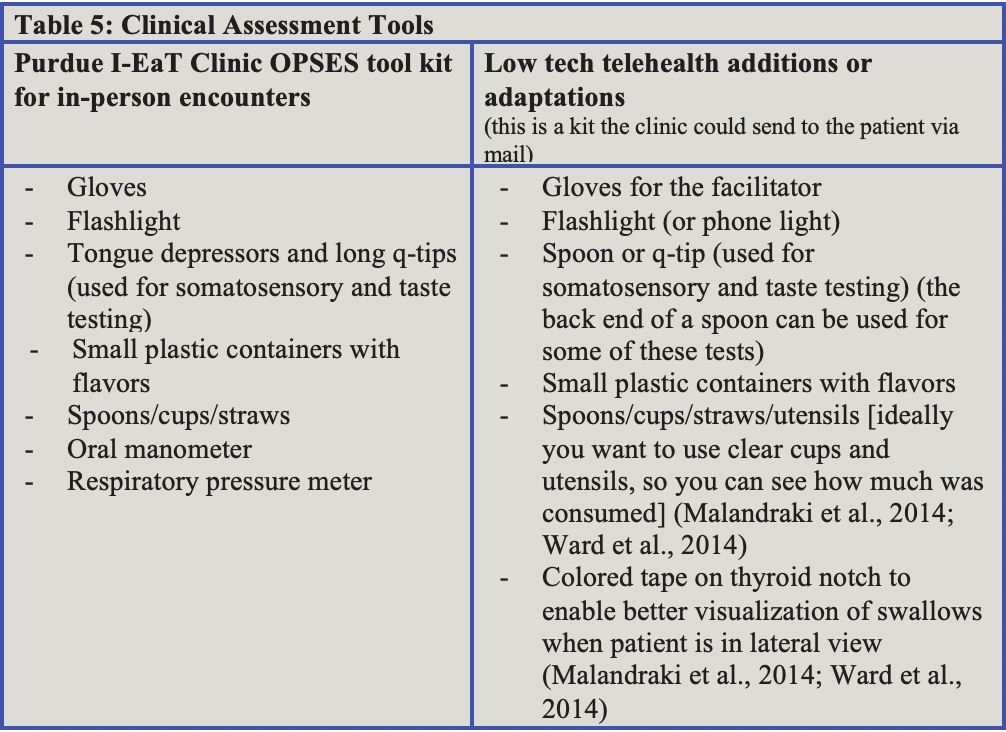

In addition to all parameters discussed thus far, for clinical swallowing assessments we also want to consider the typical tools we use to perform such an assessment. At this time, we may not have all these tools available, but we can still create a list of items that we would need and/or request to be available at both the clinician’s and the patient’s end. For example, in Table 5 you will see the main clinical examination testing items that we have in our Purdue I-EaT Swallowing Research Clinic and adaptations for our telehealth sessions.  Although, we also include cognitive screenings and quality of life assessments in our clinical evaluations, the discussion of these types of assessments/tools and their use for telehealth was discussed earlier. The reason to have these items available at both ends of the connection (clinician and patient) is so that the clinician can use these items to model targeted behaviors, and so that the patient can perform the different tasks, ideally with the help of a facilitator/caregiver (e.g., Malandraki et al., 2014; Raatz et al., 2019). Reinforcements (used for assessment or therapy) in the form of either online “Great job” cards that you screen share, or in the form of actual or virtual favorite items appearing on the screen or on camera can be particularly useful for pediatric patients or patients with intellectual and developmental disability. An example can be seen in the image below.

Although, we also include cognitive screenings and quality of life assessments in our clinical evaluations, the discussion of these types of assessments/tools and their use for telehealth was discussed earlier. The reason to have these items available at both ends of the connection (clinician and patient) is so that the clinician can use these items to model targeted behaviors, and so that the patient can perform the different tasks, ideally with the help of a facilitator/caregiver (e.g., Malandraki et al., 2014; Raatz et al., 2019). Reinforcements (used for assessment or therapy) in the form of either online “Great job” cards that you screen share, or in the form of actual or virtual favorite items appearing on the screen or on camera can be particularly useful for pediatric patients or patients with intellectual and developmental disability. An example can be seen in the image below.

In our clinic, comprehensive assessments of the cranial nerves involved in swallowing are an integral part of our clinical evaluation (known as oropharyngeal sensorimotor assessments). This is because, this assessment in addition to the knowledge of the patient’s history, and the underlying pathophysiology of their disease, help guide our treatment decisions. Examining the integrity of most motor components of the cranial nerves is relatively straightforward via telehealth. Sensory and taste components need the help of a facilitator (Video coming soon!). Positioning of the camera/device at the patient’s end may need to be adjusted for the different views and head and neck areas we want to visualize for each examination component. This is something that either the patient or the facilitator/caregiver can help with, following our instructions.

If trial swallows are part of the clinical swallowing assessment, use of clear cups and utensils will help visualize amounts of liquids/foods consumed although confirmation by the patient or caregiver will also be important, as not all foods and liquids are fully visible via telehealth (Malandraki et al., 2014; Ward et al., 2014). Further, as mentioned earlier, the use of asynchronous methods, for example, asking a parent to videotape a child consuming their typical meal or snack (Kantarcigil et al., 2016), or taking a picture of the seating of a child before the evaluation is conducted and sending the picture to the clinician (Raatz et al., 2019) can offer valuable information for clinical assessments and are highly encouraged.

The clinical assessment is a critical and necessary part of any swallowing assessment, however it is also subjective, has relatively low reliability (McCullough et al., 2000), and known limitations in terms of its depth. It is important to note that these limitations are true about the clinical swallowing assessment in general, irrespective of whether it is conducted in-person or via telehealth.

The clinical assessment is a critical and necessary part of any swallowing assessment, however it is also subjective, has relatively low reliability (McCullough et al., 2000), and known limitations in terms of its depth. It is important to note that these limitations are true about the clinical swallowing assessment in general, irrespective of whether it is conducted in-person or via telehealth.

In the past few weeks, several clinicians have reached out to ask about the usage of specific validated clinical screening or clinical evaluation tools for telehealth assessments. In regular clinical practice, supplementing the clinical assessment with the use of validated evaluation tools can further standardize our assessment and improve reliability and validity of our outcomes. However, to our knowledge, none of currently available validated swallowing screening or clinical assessments have been validated or tested for reliability for online telehealth delivery. One exception is the Dysphagia Disorders Survey (Sheppard et al., 2014), which has been tested for inter- and intra-rater reliability in an asynchronous telehealth delivery mode, but in a relatively small study with children with cerebral palsy (Kantarcigil et al., 2016). Given this critical gap, if established validated clinical swallowing assessments or screenings are used via telehealth, interpretation of these should be done with extreme caution. Specifically, clinicians are advised to: a) reach out to test developers to ask if online versions are available and/or ask for their professional opinion, permissions, and limitations on remote/telehealth usage, b) use such tests only to supplement other aspects of the clinical assessment (such as the cranial nerve exam, the cognitive screen, and the case history information), and not as definitive stand alone evaluations, and c) if they decide to use a specific validated tool to supplement their tele-clinical evaluation services, they need to disclose such usage and its limitations in their documentation (see later section on documentation for details).

Important additional note in regards to tele-clinical swallowing assessments

With rare exception, completion of the clinical swallowing assessment alone is not sufficient to definitively make recommendations for treatment. In most situations, referrals for instrumental evaluations are essential. It is understandable that at this time, in many facilities instrumental assessments are triaged and only necessary and urgent procedures are being conducted. Therefore, many instrumental swallowing assessments are being postponed. In this situation when an instrumental assessment is postponed, in our professional view, potential avenues should be considered in close collaboration with the medical team and take into account a holistic and patient-centered approach. These avenues may include:

- For more severe patients, conservative recommendations for temporary alternative feeding method, depending on patient’s history and current health status

- Recommendations for meticulous oral hygiene, customized to the needs of each patient

- Examining the potential of an adapted or modified Free Water Protocol, if patient and facility is appropriate

- In select situations, we may be able to consider conservative recommendations for indirect treatment approaches (i.e., approaches that do not involve food intake) based on the clinical swallowing assessment results, or skill-based approaches targeting the oral stage.

All aforementioned avenues have distinct benefits and risks, advantages and disadvantages, and need to be considered on a case-by-case basis and after a thorough risk/benefit ratio has been estimated by the medical team.

4. Specific tools and tips for clinical swallowing tele-therapy

Many of the tools and procedural tips suggested for the tele-clinical swallowing assessment can be useful for swallowing tele-therapy as well. For tele-treatments, a few things that we have found to be particularly helpful to ensure treatment fidelity include:

- Adequate modeling of the strategy being taught. This can be done via the remote clinician modeling the strategy or via the use of cartoon like figures (for children) or real instructional videos (for adult patients).

- Creating scripts and visual aids including specific step-by-step directions you would like the patients to follow may be very helpful. This can also facilitate consistency and standardization of treatment approaches across patients, and can be extremely helpful for patients who are hard of hearing and have a hard time understanding verbal instructions, especially in the virtual environment.

- As mentioned earlier, use of customized or personalized reinforcements in the form of online “Good job” cards, or of actual or virtual favorite items appearing on the screen or on camera can be particularly useful for pediatric patients or patients with intellectual and developmental disability.

- Finally, having specific rules and guidelines about when facilitator/aid is to intervene during treatment and reminding these guidelines to the facilitator and the patient in the beginning of each session will be critical.

5. Documentation

Documentation should adhere to all legal and clinical standards of care, and to insurance requirements (Burns & Wall, 2017; Gough et al., 2015).

Documentation of Evaluation Tele-Encounters

For telehealth evaluation services, specifically, documentation needs to include (ASHA Telepractice Portal, n.d.; Burns & Wall, 2017; Gough et al., 2015; Turvey et al., 2013):

- Date and time of session

- Specifics on the environment where the evaluation occurred

- A statement that it was conducted via telehealth

- The specific technology platform used

- The specific tests used

- Adaptations made to the tests and how these adaptations may impact their validity

- A clear statement about each test’s validity and reliability for online usage and any further testing recommended

- Facilitator’s role and patient responses

- Any technical or clinical extenuating circumstances or adverse events that occurred during the session

Documentation of Treatment Tele-Encounters

For telehealth treatment services, documentation needs to include (ASHA, n.d.; Burns & Wall, 2017; Gough et al., 2015; Turvey et al., 2013):

- Date and time of session

- Specifics on the environment where the treatment occurred

- A statement that it was conducted via telehealth

- The specific technology platform used

- The specific tools used (if appropriate)

- Any adaptations made to the tools and how these adaptations may impact results

- Facilitator’s role and patient responses

- Plan for follow-up/next session

- Any technical or clinical extenuating circumstances or adverse events that occurred during the session

Documentation of Emergency Encounters

Any emergency encounter also needs to be documented. Specifically, for emergency encounters, clinicians are advised to document (Gough et al., 2015):

- Date and time of the encounter

- The location of the patient when the emergency situation occurred

- The exact process followed to treat/address the emergency situations

- Any referrals made as a result of the emergency situation, including the recommendations of the referral source (if witnessed)

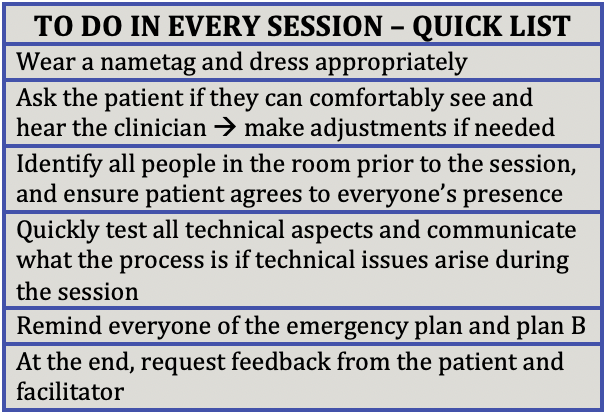

6. To do in every session

Finally, below are some additional administrative recommendations that should be followed in every session (ATA, 2014; Gough et al., 2015; Krupinski, 2014). These recommendations are also consolidated in the table below.

- First, ideally we should be wearing a nametag, so that our name

and credentials are fully visible to the patient.

and credentials are fully visible to the patient. - Early on, the patient should be asked if they could comfortably see and hear the remote clinician. If adjustments need to be made, the facilitator should help with these adjustments.

- As a next step, we should identify all people in the room prior to the session, and all people/students in the tele-room (in cases of telesupervision) and ensure patient’s agreement to everyone’s presence.

- Next, we should quickly test all technical aspects initially to ensure that everything is working appropriately. Also, communicate what the process will be if technical issues do arise during the session.

- Reiterate the Plan B and the emergency plans so that everybody remembers and is still aware of these important plans, in case something goes wrong. Confirm contact details with the patient/family, in case of an interruption or emergency.

- At the end of each session it will also be important to request feedback from the patient and the family to see what aspects can be improved, and make plans for the next appointment/session.

3. Quality improvement and performance management

Most published policy documents on telehealth highlight the importance of having in place a systematic quality improvement and performance management process (ATA, 2014; Richmond et al., 2017; Gough et al., 2015 and more). This process should entail quality assurance and quality control and comply with organizational and professional requirements. What this means is that clinicians and facilities who develop a telehealth program should review the program periodically to identify what components work well and what need improvement, and determine any risks and how to mitigate them. Assessment metrics for review and quality control that have been proposed include: quality of equipment and connectivity and any failures, number of attempted and completed visits, patient and clinician satisfaction, clinical outcomes, and appropriateness and comfort level with telehealth delivery (ATA, 2014; Gough et al., 2015, Richmond et al. 2017). For dysphagia telehealth programs, Burns and Wall have suggested the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, which provides guidance on how to integrate all aforementioned components into a new program and evaluate its clinical and operational effectiveness (Burns & Wall, 2017).

Conclusion

This is a challenging time for humanity and for all health professionals. Although urgent decisions need to be made for us to continue to provide needed care to our patients, our actions must be thorough, safe, and ethical, as well abide by federal and state laws, legal and procedural recommendations and the ASHA Code of Ethics.

Test your knowledge through this self quiz!

1. Although there is overall a growing body of positive research evidence for the use of telehealth for dysphagia management, what also must be kept in mind about these positive outcomes before “jumping into” implementation?

2. True or False: Choosing a specific service or method to obtain legal documents’ signature needs to be approved by your legal counsel/risk management team.

3. Multiple choice: Typical training guidelines for facilitators should include which of the follow topics?

| a. Clear delineation of the emergency plan |

| b. Clear instructions/rules about when the facilitator may intervene and override the remote clinician |

| c. Detailed instructions on how to prepare for the session |

| d. a and c |

| e. All of the above |

4. According to ATA guidelines, bandwidth should be at a minimum of ____________ for both upload and download, and should provide a minimum of 640 x 360 resolution at _______ frames/second.

5. List 3 adaptations you can make to create an environment as conducive to providing clinical services as possible?

6. Why is it important for both the clinician and patient to have all materials/tools during the sessions?

7. Multiple choice: If established/published validated clinical swallowing assessments or screenings are used via telehealth, clinicians are strongly advised to:

| a. Reach out to test developers to ask if they have online versions available |

| b. Interpret results with extreme caution |

| c. Use such tests only to supplement other aspects of the clinical assessment, not as stand alone evaluations |

| d. Disclose the assessment or screening was given via telehealth and mention its limitations in documentation |

| e. All of the above |

8. Describe the dysphagia-specific candidacy criteria we need to consider to determine if a patient is a good candidate for telehealth services?

9. Multiple Choice: These are some of the actions recommended to be completed in every tele-session:

| a. Identify all people in the room and ensure the patient’s permission for everyone’s presence |

| b. Test all technical aspects and have a protocol for when technical issues arise |

| c. Remind everyone the emergency plan |

| d. All of the above |

10. List 5 practical adaptations you would need to make to ensure the feasibility and validity of a tele-clinical swallowing evaluation

Content created by Dr. Georgia A. Malandraki, Ph.D., CCC-SLP, BCS-S / Web support/development: Samantha Mitchell