Computing for contentment: Purdue scientist uses AI to model fairness and maximize the benefits of donated food

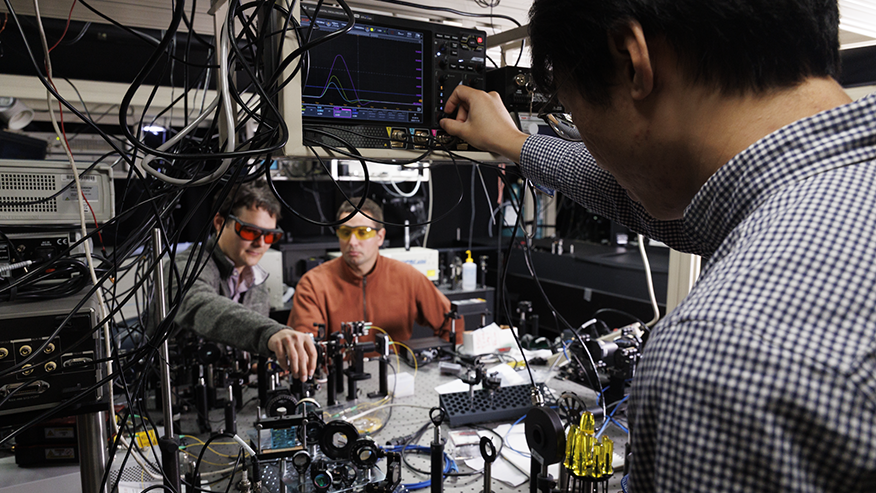

Alex Psomas, an expert in training artificial intelligence models to aid in human decision-making, works with a nonprofit food bank to help automate and maximize the benefits of donated food. (Purdue University photo/John Underwood)

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — A coin flip. A roll of the dice. A shake of the Magic 8 Ball. Humans have been outsourcing their decision-making to inanimate objects since long before recorded history.

But when a Magic 8 Ball reports “outlook good,” it’s random chance. It lacks any information about the situation. Alex Psomas, assistant professor of computer science in Purdue University’s College of Science, is designing artificial intelligence models to outsource decisions to make better, more informed and fairer choices, including how best to distribute food among food pantries in Indianapolis.

The process takes all the emotion out of the equation, something humans find impossible to do, and harnesses innovative AI models to weigh all the possible considerations and come up with the solution that best benefits the most people.

Psomas is teaching dispassionate computers to help humans make weighted — and weighty — decisions, including how best to allocate food pantry resources. It’s not just a question of deciding who “deserves” an apple between two people. It is quantifying how many people have what degree of need and how much each resource can help them and improve their lives.

“Economists think about value as being quantitative,” Psomas said. “The utility I have for an object, like a phone, or like a carton of food, depends on my priorities, my circumstances and my values. Any calculation has to take into account everyone’s viewpoints and make everyone happy with the outcome so that it feels fair to everyone. There are lots of different ways to define fairness, but our goal is no envy. That’s the gold standard. We want everyone to be happier with what they get versus what someone else got.”

Fair and square

Technically, flipping a coin, the simplest possible decision-making aid, is binary. That binary code forms the basis of how computers think, but the process has advanced light-years in the last century, and even in the last few years.

“I really care about big applications, but, at the same time, I’m a theoretician,” Psomas said. “I just do a bunch of math all day, and for me one of the coolest things about this project is that, not only are the outcomes beneficial, but the math is actually pretty cool. The math we’re using is based on a set of ideas that were revolutionary in computer science.”

The revolution is what is referred to as “load balancing.” Load balancing techniques are used to regulate situations including distributing network traffic in a router to be sure that everyone gets the best possible speed.

Psomas’ background is in computer science and logic. He has worked extensively with systems where he uses numbers to model nebulous ideals, including incentives, fairness and value.

“I am very interested in problems in economics,” Psomas said “My strength is approaching economics problems from a computer science angle and approaching computer science problems from an economic angle.”

The fields of economics and mathematics, especially the math used in AI models, have a great deal in common, but not many researchers are conversant in both worlds as is Psomas. Potential applications for this kind of work include new possibilities for solving societal struggles, including regulating organ donation, incentivizing preventative health care and distributing water for fair use. As part of the Purdue Computes initiative, Psomas works to advance the frontiers of computer science and AI.

“There are tons of a traditional optimization problems, but with fairness factored in,” Psomas said. “They are very fascinating problems, and the solutions can save lives.”

Thought for food

One of his more recent, and dynamic, projects included a more efficient way to distribute food donations to food banks in partnership with the Indy Hunger Network.

The Indy Hunger Network has an initiative, known as Food Drop, that allows shipments of edible food to be efficiently donated to food banks. Food may be rejected from a grocery store, restaurant or other consumer because of logistical errors or imperfections, but the food is still perfectly edible. Traditionally, that food would be bound for the landfill. Food Drop instead allows this food to be donated to a food bank.

“They would call around to food banks and figure out who could take the load of food — who needed it the most. But those calls took resources. We worked with them to automate the system to figure out, automatically, where the food should go.”

Psomas’ innovative machine learning program saves time and energy, making automatic allocations rather than just recommendations. The Indy Hunger Network staff no longer has to call around to food banks, which requires the food banks to answer the phone and be able to instantly relay information. And the truck drivers no longer have to idle, waiting to be given a destination. He talks more about the program in this video.

This work, joint with Psomas’ graduate students Marios Mertzanidis and Paritosh Verma, appeared in the Association for Computing Machinery’s Conference on Economics and Computation 2024 and recently won the award for best student paper at the Association for Computing Machinery’s Conference on Equity and Access in Algorithms, Mechanisms and Optimization 2024.

“This is one of the largest-scale systems that we know of that uses AI to help food distribution and explicitly models and addresses considerations of fairness,” Psomas said. “We built it, we automated it, we maintained it, and now we’ve handed it off to the Indy Hunger Network to use. It’s open source: The code is out there for anyone to use. I hope this grows beyond Indiana. The computers can free up the humans to address other problems, and everyone gets fed. It’s a win-win.”

Psomas’ research is funded by the National Science Foundation, as well as a Google AI for Social Good award.

About Purdue University

Purdue University is a public research institution demonstrating excellence at scale. Ranked among top 10 public universities and with two colleges in the top four in the United States, Purdue discovers and disseminates knowledge with a quality and at a scale second to none. More than 105,000 students study at Purdue across modalities and locations, including nearly 50,000 in person on the West Lafayette campus. Committed to affordability and accessibility, Purdue’s main campus has frozen tuition 13 years in a row. See how Purdue never stops in the persistent pursuit of the next giant leap — including its first comprehensive urban campus in Indianapolis, the Mitch Daniels School of Business, Purdue Computes and the One Health initiative — at https://www.purdue.edu/president/strategic-initiatives.

Podcast

Podcast Ep. 128: How Purdue Is Using AI for Good — Computer Science Professor Alex Psomas Explains

Media contact: Brittany Steff, bsteff@purdue.edu

Note to journalists:

A video link is available to media who have an Associated Press subscription.