March 20, 2019

C-sections are seen as breastfeeding barrier in the U.S., but not in other global communities

A photo of a Yucatec Maya mother and newborn is featured on the cover of the American Journal of Human Biology. (Photo provided by Rosy Garibay)

Indigenous Mexican mothers practice prolonged breastfeeding even after C-sections and their babies benefit

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — The increase in cesarean sections is on the verge of a global epidemic. Though the World Health Organization recommends an optimal C-section rate of 10-15 percent, the United States’ C-section rate is more than 30 percent.

In many Latin American countries, the procedure is sky rocketing, reaching more than 50 percent in some.

While C-sections are lifesaving in some cases, they are increasing beyond recommended rates with harmful consequences for children’s health.

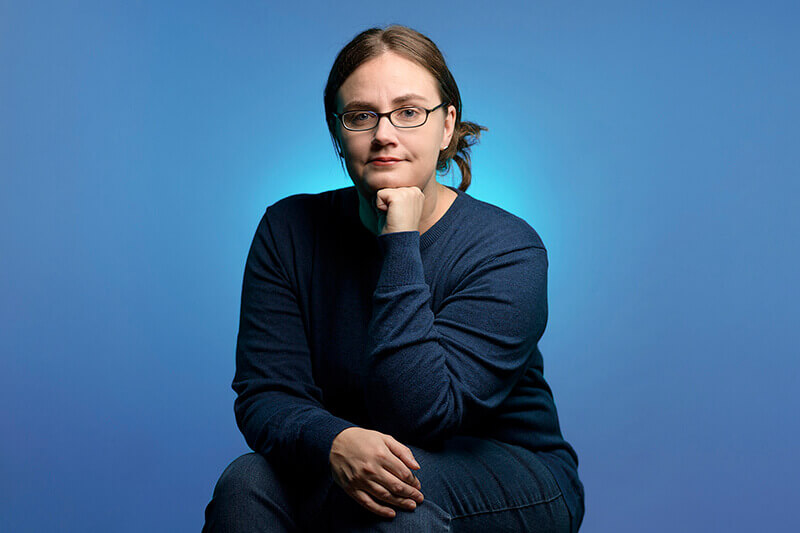

Amanda Veile, an assistant professor of anthropology at Purdue University, who is a biological anthropologist specializing in infant and child development. (Purdue University photo/Rebecca Wilcox)

Download image

Amanda Veile, an assistant professor of anthropology at Purdue University, who is a biological anthropologist specializing in infant and child development. (Purdue University photo/Rebecca Wilcox)

Download image

Cesarean delivered children tend to be susceptible to infections, obesity, asthma and allergies. This occurs in part because many mothers are unable to successfully breastfeed them after a C-section.

However, recent research shows that this may be culturally mediated. In some parts of the world, mothers are able to breastfeed successfully after C-section deliveries, and this practice may reduce their negative child health effects.

Amanda Veile, an assistant professor of anthropology at Purdue University, and her team report that indigenous mothers in farming communities in Yucatán, Mexico, breastfeed for about 1.5 months longer following cesarean deliveries than they do following vaginal deliveries. Veile believes this is possible because the mothers live in an exceptionally supportive breastfeeding environment.

“Moms living in this Mexican community don’t have to hide in a bathroom to feed their child when they are in public,” says Veile, a biological anthropologist who specializes in infant and child development. “Here, it is a cultural norm to breastfeed anytime, anywhere, and to sustain breastfeeding for longer than two years. And we think that prolonged breastfeeding offers protective benefits that reduces some of the health problems we often see in children delivered by C-section.” Model of a human pelvis. (Purdue University photo/Rebecca Wilcox)

Download image

Model of a human pelvis. (Purdue University photo/Rebecca Wilcox)

Download image

Veile’s research appears in the American Journal of Human Biology’s special issue on the evolutionary and biocultural causes and consequences of rising cesarean delivery rates. Veile and collaborator Karen Rosenberg, a professor from the University of Delaware, are the guest editors for the special issue. It features 10 research articles written by anthropologists, biologists and healthcare practitioners, which are available open access through spring 2019.

In Veile’s study, she and her team compared breastfeeding durations and childhood infection rates based on how the child was born to Yucatec Maya farmers. Following 88 children from birth until age 5, the results show that those children born via C-sections were breastfed for about 2.7 years, whereas vaginally delivered children were breastfed for just over 2.5 years. There was no difference in infection rates between the two groups of children.

“What a powerful message supporting breastfeeding,” Veile says. “We need to continue studying this issue, but it seems that these mothers, perhaps subconsciously, increased their breastfeeding efforts post-cesarean.”

Veile says that Yucatec Maya women do experience post-cesarean challenges in the hospital environment, such as prolonged separation from their infants, latching issues and delayed milk let-down reflex. Still mothers overcome these challenges through determination, consumption of special foods, and the use of herbs and compresses. They also receive emotional support and breastfeeding advice from their family and friends.

“Now that C-sections are becoming more universal, it is important to understand more about the consequences for children’s health in a variety of settings,” Veile said. “This includes very rural communities worldwide that are transitioning to increased health care access, while simultaneously experiencing poor community sanitation and the double burden of malnutrition.”

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation, Purdue Research Foundation and Dartmouth College. Veile collaborated with Sydney M. Tuller, graduate student in Purdue’s Department of Anthropology; Amy A. Faria, graduate student in Purdue’s Department of Consumer Science; Sydney Rivera, medical student at the Indiana University School of Medicine; and Karen L. Kramer, professor of anthropology at the University of Utah.

Other research by Veile examined childhood growth patterns and environmental health issues in indigenous children as related to C-sections. Veile is the director of the Laboratory for Behavior, Ontogeny and Reproduction (LABOR), which studies maternal reproductive biology and the immuno-nutritional development of infants and children. In addition to Mexico, she has conducted research in Bolivia, Venezuela and Peru.

The work aligns with Purdue's Giant Leaps celebration, acknowledging the university’s global advancements made in health, longevity and quality of life as part of Purdue’s 150th anniversary. This is one of the four themes of the yearlong celebration’s Ideas Festival, designed to showcase Purdue as an intellectual center solving real-world issues.

Writer: Amy Patterson Neubert, 765-494-9723, apatterson@purdue.edu

Source: Amanda Veile, aveile@purdue.edu

Note to Journalists: Journalists interested in a copy of the journal article can contact Amy Patterson Neubert, Purdue News Service, 765-494-9723, apatterson@purdue.edu

ABSTRACT

Birth mode, breastfeeding and childhood infectious morbidity in the Yucatec Maya

Amanda Veile, Amy A Faria, Sydney Rivera, Sydney Tuller, Karen L. Kramer

DOI: 10.1002/ajhb.23218

Objectives: Cesarean delivery is linked to breastfeeding complications and child morbidity. These outcomes may disproportionately affect Latin American indigenous populations that are experiencing rising cesarean delivery rates, but often inhabit environments that exacerbate postnatal morbidity risks. We therefore assess relationships between birth mode, infant feeding practices and childhood infectious morbidity in a modernizing Yucatec Maya community, where prolonged breastfeeding is the norm. We predicted that under these conditions, cesarean delivery would increase risk of childhood infectious morbidity, but prolonged breastfeeding post cesarean would mitigate morbidity risk.

Methods: Using a longitudinal child health dataset (n = 88 children aged 0-60 months, 24% cesarean-delivered, 2290 observations total), we compare gastrointestinal infectious (GI) and respiratory infectious (RI) morbidity rates by birth mode. We model associations between cesarean delivery and breastfeeding duration, formula feeding and child nutritional status, then model GI and RI as a function of birth mode, child age, and feeding practices.

Results: Cesarean delivery was associated with longer breastfeeding durations and higher child weight-for-age, but not with formula feeding, GI, or RI. Adolescent motherhood and RI were risk factors for GI; formula feeding and GI were risk factors for RI. Regional housing materials protected against GI; breastfeeding protected against RI and mitigated the effect of formula feeding.

Conclusions: We find no direct link between birth mode and child infectious morbidity. Yucatec Maya mothers practice prolonged breastfeeding, especially post cesarean and in conjunction with formula feeding. This practice protects against childhood RI, but not GI, perhaps because GI is more susceptible to maternal and household factors.