January 29, 2019

Deceiving the deceivers

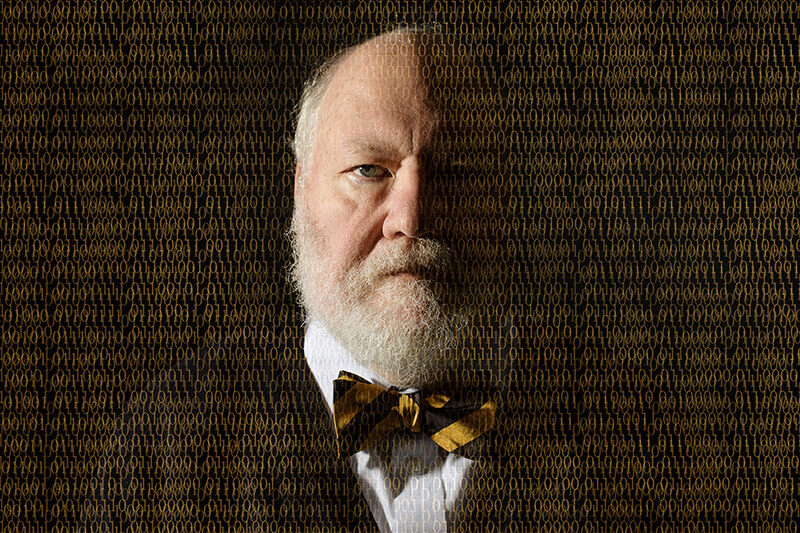

Eugene H. Spafford, a professor of computer science, leads research on how to use deception as another tool to thwart ongoing cyberattacks from hackers. (Purdue University photo/Rebecca Wilcox)

Cybersecurity professor employs false fronts, data to fool hackers

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — “God” was protecting part of the Purdue computer system from hackers in the early 1990s.

Computer users without authorization that tapped into “God” – a booby-trapped computer file – were hit with a prompt with the name of each file in their directories. Any reaction resulted in a “Deleted!” message for a file.

While the users believed their files were slowly destroyed, “God,” in fact, was sending its creator information about who was trying to run the computer file and from where.

“God” was among the many early active computer defenses created by Eugene H. Spafford, one of the first convinced that the idea “Things aren’t always as they seem” isn’t a weapon only for malware creators. And things have come full circle as his early 1990s research is again becoming a tool in the ongoing war to protect personal and business information.

Spafford, still one of the preeminent leaders in the field of cybersecurity, has worked for years to build secure computer systems and, in computer forensics, help investigate and prosecute by pushing through the deceit used by hackers.

Most people don’t know when they’ve been hacked, with millions affected in 2018, amounting to tens of billions of dollars lost. More than 750 million people were affected by hacker-led cyberattacks in April, May and June alone.

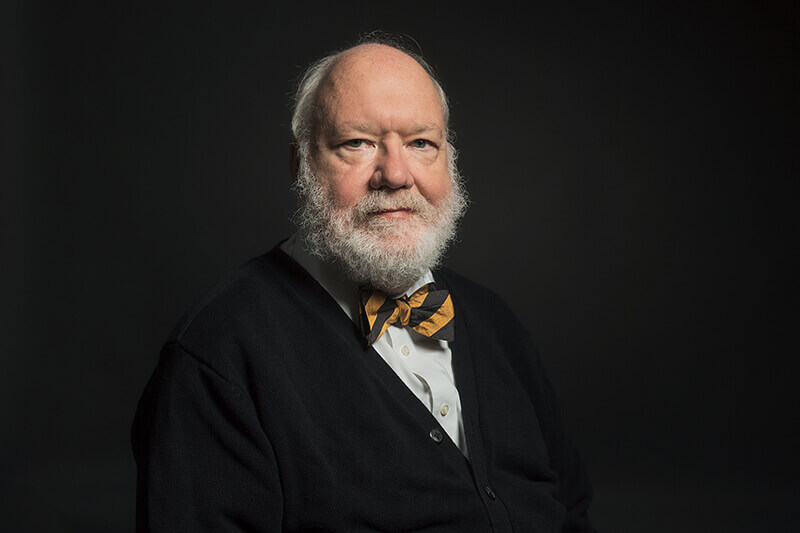

But now, Spafford has re-initiated then-classified work he began for the Air Force in the 1990s and started putting deception to use in protecting important systems and data. Eugene H. Spafford. (Purdue University photo/Rebecca Wilcox)

Eugene H. Spafford. (Purdue University photo/Rebecca Wilcox)

Download image

“It’s not been lost on me over time that you can still deceive the deceivers,” said Spafford, a professor of computer science at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. “The intent is to find ways to prevent an attacker from getting an accurate view of what they are trying to attack and mislead them about their results.”

Deception has been an interest of Spafford dating back to his childhood days of playing spies with secret messages. That eventually dovetailed with a blossoming hobby interest in computers and early cybersecurity, including some consulting work that paid for a few graduate school expenses.

Taking the work in a different direction, the research looks past false hosts or networks and is focused on false services or applications as well as using false security data that entices someone who may want to intercept it.

Spafford coordinated the response to the Morris Internet worm, one of the first computer worms distributed via the Internet, in November 1988.

A member of the Cybersecurity Hall of Fame, Spafford has a served as a senior adviser or consultant for two U.S. presidents, as well as the Air Force, the National Security Agency, the FBI, the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Department of Energy, not to mention technology giants Microsoft and Intel.

With over three decades of experience as a researcher and instructor, he has been honored with every significant award in cybersecurity.

Cybersecurity can be a multidisciplinary field. Spafford, who also has courtesy appointments in communications, philosophy, political science and electrical and computer engineering, said deceiving hackers is a perfect example.

“There’s some psychology involved in this because people are more prone to believe certain kinds of lies than others,” he said. “It’s important in how you sell it.”

Just as important is the question of when cybersecurity deception can be used ethically.

The art of deception in cybersecurity has earned the attention of several companies and government agencies who are working to construct measures of deception, including building it into existing tools, to protect valuable systems and critical infrastructures.

For a field that is among the most rapidly developing in the last 100 years, cybersecurity is oftentimes misrepresented and misunderstood.

“There are a lot of people outside of the field that think it’s only a matter of stopping viruses and applying patches,” Spafford said. “That is the equivalent of thinking that practicing medicine is giving people penicillin and splinting broken bones. There’s far, far more to it than that.”

That rapid development and evolution creates a continuous cycle of examining and re-examining ideas and solutions to make sure they’ve transitioned as quickly as cybersecurity has. That’s not always the case with operating systems from the ’90s with limited memory and bandwidth still in use despite the Internet of Things and processors with huge memories coming into their own.

“Part of it is re-examining design decisions that were forced on us, and part of it is looking at problems to solve them using mechanisms that are now available to us,” Spafford said. “We need to look at previous assumptions and ask, ‘Do those hold now? What if we change those?’ Then we work forward from there.”

Some outside-the-box thinking is also necessary. Spafford focused his work on computer viruses and malware by studying epidemiology (the branch of medicine dealing with the incidence, distribution and control of diseases), specifically what has been done to battle recurring diseases and infections.

“One of the best things in life is doing something you’re passionate about – that’s what happened to me,” he said. “I’ve always been enthused and interested and had ideas in the area.”

Spafford’s research aligns with Purdue’s Giant Leaps celebration, acknowledging the university’s global advancements made toward a sustainable economy and planet as part of Purdue’s 150th anniversary. This is one of the four themes of the yearlong celebration’s Ideas Festival, designed to showcase Purdue as an intellectual center solving real-world issues.

Writer: Brian Huchel, 765-494-2084, bhuchel@purdue.edu

Source: Eugene Spafford, 765-494-7825, spaf@purdue.edu