You can’t always get what you want, but with dynamic lotteries you get what you need

Sometimes there isn’t enough for everyone to get what they want. In an increasingly populous world, resources that belong to all, like water, electricity and road access, may need to be rationed. How can such resources be allocated in a way that is fair and efficient? Dynamic lotteries may be the answer, and a real-world study of a hunting license system supports the economic theory.

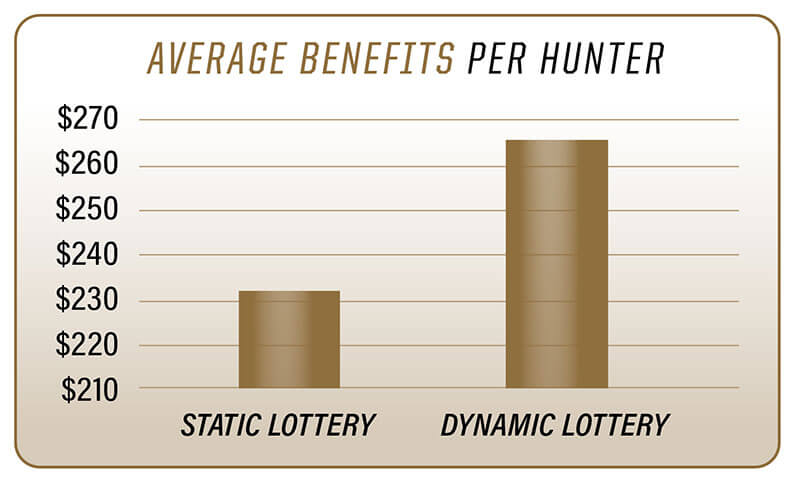

“Most of the time, price dictates who gets an in-demand item, but we can all agree there are certain resources that shouldn’t simply go to the highest bidder,” said Carson Reeling, an associate professor of agricultural economics at Purdue University who led the study. “A dynamic lottery levels the playing field, but still sorts out who values a resource the most. It also, according to our study, improved the well-being of the participants relative to other non-price means of allocating resources.”

In a dynamic lottery, individuals are periodically given a stock of points they are able to either spend on a resource or save, Reeling said.

“The points are like monopoly money and everyone begins with the same amount,” he said. “Even though it isn’t real money, people tend to treat it like it is and use it wisely according to what they value most. It is an accepted economic theory of efficient allocation, but it had never been tested in the real world and shown to work.”

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources uses this type of system in its distribution of bear hunting licenses, he said. Participants are given so-called “preference points” to vie for licenses for particular regions of the state and for different times. Participants earn preference points for each year they skip or do not receive a license, and those with the most preference points are given priority for a license. If one is awarded a license, their preference points return to zero.

Reeling collaborated with Valentin Verdier, an assistant professor of economics at the University of North Carolina, to build statistical models to analyze the system and behavior of the participants, and measure participants’ well-being. The complex mathematical problems involved required the use of supercomputers to run the models.

A paper describing the work was published in the journal The Review of Economic Studies.

“We found that the system worked very well as compared to a static lottery, which is effectively just drawing names out of a hat,” Reeling said. “Dynamic lotteries introduce opportunity costs. If a hunter spends their preference points, they lose the opportunity to hunt for the next few years while they build up their stock again. This opportunity cost, which is not present in other types of lotteries, makes hunters more selective about where and when they apply to hunt. It also drives really interesting behavior.”

Based on what each person valued the most, the hunters self-sorted into groups. Some valued frequent hunting and spent their points as they received them. Others valued the quality of the hunting area and saved their points in order to receive priority for those licenses. Others fell in the middle, he said.

The team evaluated participants’ well-being by examining how hunters trade off hunt access and the costs of traveling to different hunting sites.

“If we know a hunter chose to apply for a license to one site over another, then this must mean that the benefits they expect to get from that site — net of the costs of traveling there — must be greater than the net benefits they expect to get from the other site. This means we can use differences in travel costs between sites as a proxy for the relative value of different sites.”

The team’s model allowed them to simulate hunters’ behavior under different license allocation systems. They could use these simulation results to estimate how the benefits to hunters change under each system.

“Although this was a study of hunting licenses, the findings have implications for allocation of other resources,” Reeling said. “For instance, driving permits in parts of China are allocated to avoid traffic congestion. In the future, more complex allocation of who uses electricity or water at particular times of day may need to be made when these systems are strained. As the world’s population increases, resource management will become more and more important. We will need efficient and fair methods to allocate those resources, and that is what I’m pursuing.”

Reeling next is working with the Indiana Department of Natural Resources to analyze demand for deer hunting licenses. He is part of an interdisciplinary team that also will incorporate deer population dynamics to enhance benefits for both the hunters and the health of the deer population.

Writer: Elizabeth K. Gardner, 765-441-2124, ekgardner@purdue.edu

Source: Carson Reeling, 765-496-6197, creeling@purdue.edu